Table of Contents

Page List

Guide

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Melissa Harper 2020

First published 2007

New edition 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

| A catalogue record for this

book is available from the

National Library of Australia |

ISBN9781742236674 (paperback)

9781742244945 (ebook)

9781742249483 (ePDF)

Internal design Josephine Pajor-Markus

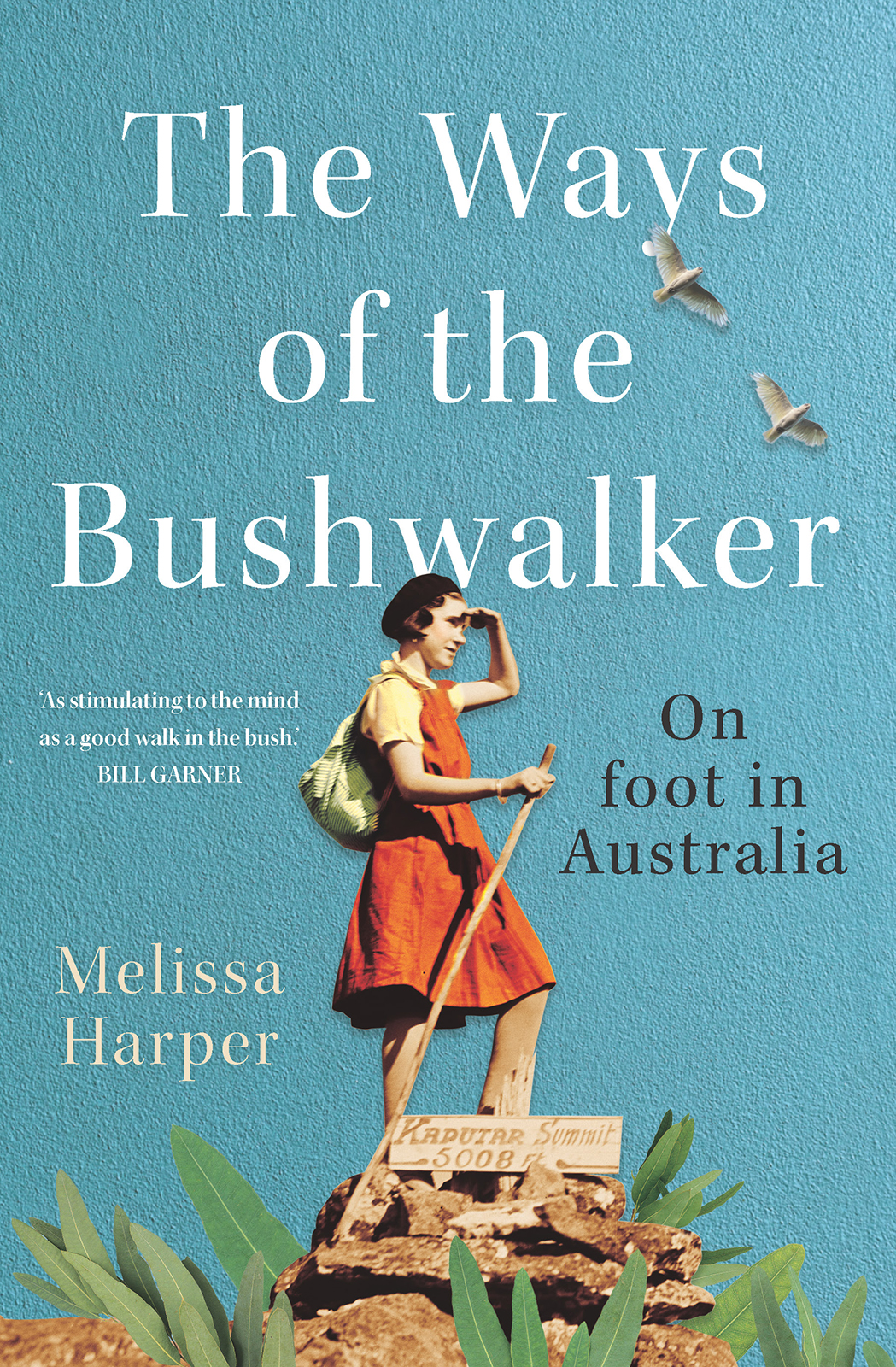

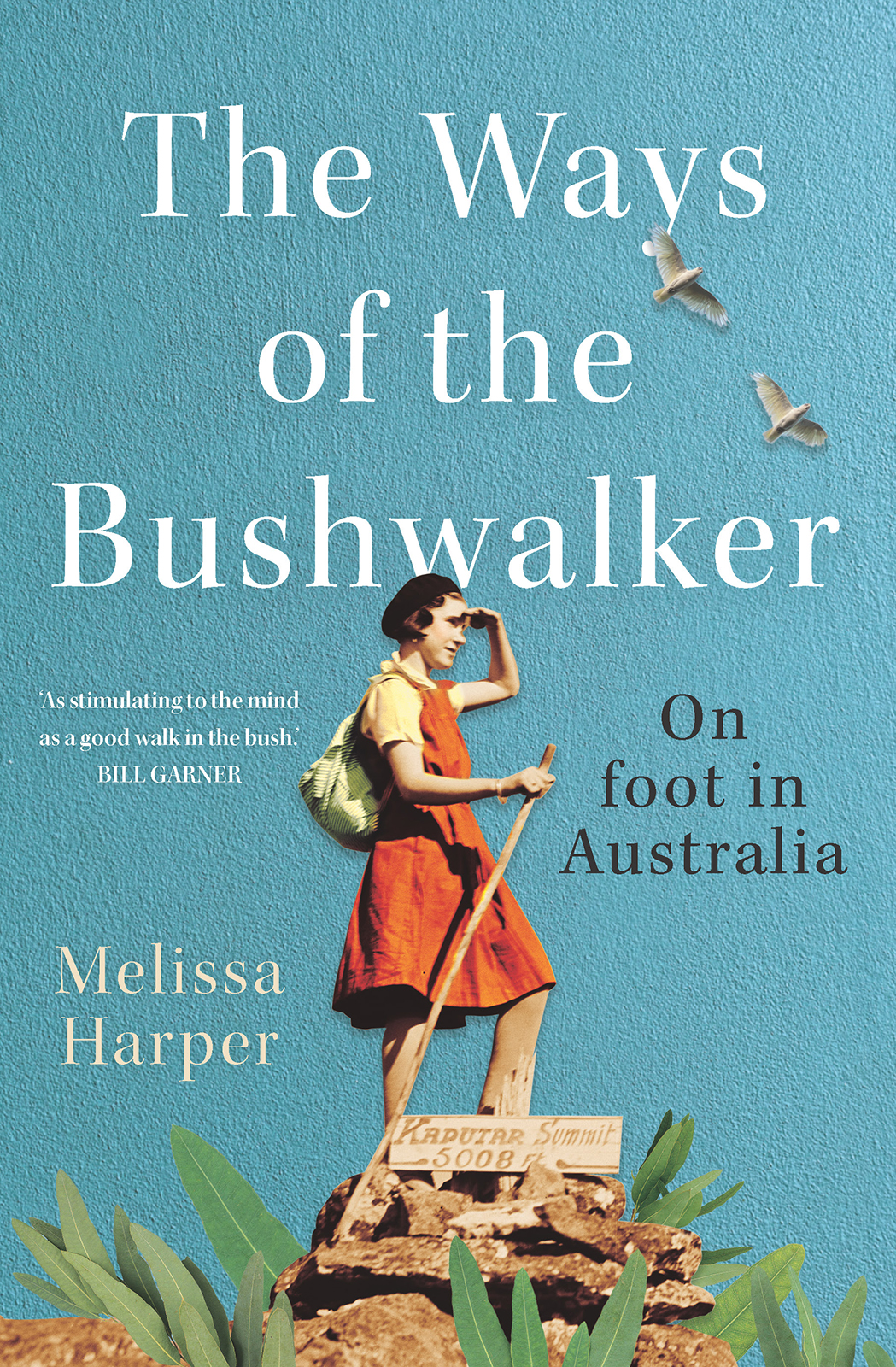

Cover design Nada Backovic

Cover image Woman on the summit of Mount Kaputar, New South Wales, 1932 ( Fishwick, Herbert H., 18821957. / Sydney Morning Herald and The Age Photos, nla.obj-163065665 )

Printer Griffin Press

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

Some quotes and descriptions reflect the prevalent attitude of the time and are now considered offensive.

This book is printed on paper using fibre supplied from plantation or sustainably managed forests.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Many people and organisations have helped bring this book to completion. I am especially grateful to Richard White, who provided ongoing enthusiasm, advice and support during the PhD and beyond, including casting a critical eye over new material. Many other scholars gave valuable feedback that informed the project, including Maureen Burns, Martin Crotty, Tom Griffiths, Ivor Indyk, Ewan Morris and Joanne Tompkins. A number of people provided valuable research assistance. Thank you to Meredith Lake, Claire McClisky, Paul Newman, Lila Oldmeadow and Olwen Pryke. Thanks also to Peter McLaren and Matthew Karpin for proofreading the first edition and to Fiona Sim for her work on this edition.

I am grateful to the staff at the National Library of Australia, the State libraries of New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania, the Archives Office of Tasmania, the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, and the Library of the National Museum for their assistance and knowledge. I would especially like to thank the bushwalking clubs who gave me access to their archives, most notably the Melbourne Womens Walking Club, the Melbourne Walking Club and the Hobart Walking Club. A special thanks to those bushwalkers who shared their memories: Peter Allnut, Bill Bertram, Dot Butler, Enid Rigby, Don Smart, Jim Somerville, Harry Stephenson, Nancy Weaver and Harry Whaite.

This project received financial support from the Faculty of Arts at the University of Queensland in the form of a research grant. The Australian Academy of Humanities and the School of English, Media Studies and Art History at the University of Queensland provided publication subsidies. The Department of History at the University of Sydney gave very welcome financial and administrative support during my life as a PhD student. The School of Communication and Arts at the University of Queensland facilitated this new edition.

I am especially appreciative that UNSW Press took this project on board. John Elliot and Heather Cam proved to be very patient and supportive editors of the first edition. My heartfelt thanks go to Phillipa McGuinness at NewSouth for suggesting it was time for a new edition and for her patience, belief and enthusiasm along the way. I really wouldnt have finished this without her. Sophia Oravecz has been a very supportive project editor.

My sincere thanks to my family, especially to my parents for introducing me to the bush and for much, much more. I am also indebted to the many friends who have provided encouragement and shared their own bushwalking stories. As always, my love and gratitude to Bill, Daniel and Matthew for their forbearance as writing took over yet another holiday and the opportunity to go walking ourselves.

Preface

This book was first published in 2007. Thirteen years is time enough for new developments but it would also be easy to think that not too much would have happened to impact on bushwalking, an age-old sort of recreation. Certainly not much has changed regarding why people like to go bushwalking in the first place: to be in nature, for the physical activity, to recharge. But when it comes to who is going walking, where and how they are going and what is happening to the bush in the process, there are plenty of new tracks and pathways to explore.

The most obvious recent influence on bushwalking but also the hardest to assess in terms of ongoing impact are the devastating fires that swept through Australia in the summer of 201920. Indeed, the fires hit before summer arrived and they hit in places we didnt expect. On 8 September Binna Burra Lodge, in Queenslands world heritagelisted rainforest of Lamington National Park, was razed to the ground. The fire was one of more than fifty tearing through the state.

Binna Burra Lodge had been established in 1933, an early example of what we now think of as nature-based tourism. Over the years the Lodge and the national park became a firm favourite with families, honeymooners and bushwalkers. In articulating what was lost in the fire I was particularly struck by writer Mary-Rose MacColls obituary for Binna Burra published in the Guardian. MacColl had first visited Binna Burra as a damaged teenager on a high school biology excursion, not expecting to enjoy it. She recalled:

I do not come from a hiking family we never once visited a national park but that first experience began for me a lifelong love affair with this national park in particular and national parks more generally. And what a gift it has been. Like a mother, the rainforest at Binna Burra takes you in its arms. In one way or another, I have been in those arms ever since.

MacColl wrote of the giant trees, the understorey, the birds, and the campground she preferred over the Lodge but she also noted that I cant hope to make you understand. Youd have to go there. I knew just what she meant. Binna Burra is a place that leaves its mark long after you return home.

When summer did arrive, things got worse. Fire tore through thousands of hectares of bush in almost every state. It felt as though the whole country was burning. Australians mourned for the thirty-four lives lost, and for those whose homes and livelihoods were damaged or destroyed. We mourned too for the bush, for the trees, the plant life, the landscapes, the ecosystems and for the animals (more than a billion) that did not survive.

As the fires raged and many grew frustrated by the unwillingness on the part of those in power to discuss the links with climate change, I was reminded of bushwalker-conservationist Myles Dunphys words in 1934 that Australias European history was an Age of Wastefulness. Fire, he said, was the number one enemy that hindered the national intellect (the second was the axe, the third production beyond demand). I suspected that if Dunphy were alive today he would see the fires as a symptom and an outcome of an even more powerful threat to the national intellect: climate denial and political inaction.