100 Ways to Understand Your Cat

ROGER TABOR

writer and presenter of the BBCs Cats and Understanding Cats

In memory of my mother and my cats Tabitha and Leroy.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

We love cats because of their self-contained characters and independent lifestyles, but these also mean that we tend not to know much about what makes them tick. Whether you have a specific concern about your cat, or would simply like to know more about it, this book will provide you with a better understanding of your feline friend. Within six major subject areas, 100 key aspects of your cats life are explained, with straightforward cross-referencing to related subjects. Fascinating in-depth features also give insight into the mysterious world of the cat.

How cats work

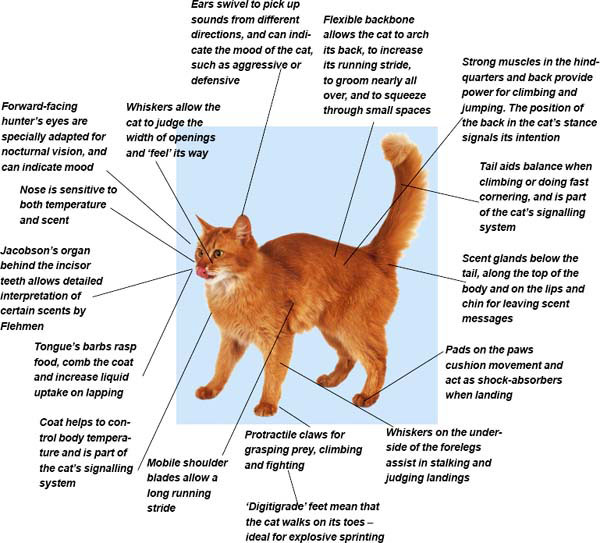

Cat construction

The structure of the cat is directly related to its behaviour as a solitary, semi-arboreal hunter with a partially nocturnal lifestyle. Each part of a cats body shows adaptations which together make it the hunter supreme, allowing it to stalk, kill and eat its prey with maximum efficiency. In addition, the cat is fiercely territorial, and its body has special mechanisms for leaving and interpreting scent messages around its home range.

1 Getting about

Fashions cat-walk is aptly named. On it models lithely parade with the same elegance of movement of a cat. Among the cats most recognizable feline characteristics is its graceful and sinuous movement. This gives the lone hunter the survival advantage it needs in the pursuit of prey.

Walking

Unlike us who walk on feet with ankles, cats and dogs are digitigrade animals, that is they walk on their toes. This has the effect of both increasing the length of their limbs and reducing the area of contact they have with the ground a necessary feature for a sprinter. In hoofed animals ground contact is reduced still further to increase their speed, but the cat, being a lone hunter, must retain the ability to manipulate its paws.

During walking, 60 percent of the cats weight is carried by the forelimbs, and consequently they provide proportionately more support, while the hindlimbs primarily provide propulsion. Cats move alternate opposite paws while walking and tend to have an unhurried air.

Running

The cat is an explosive sprinter it does not go in for long chases. As a lone hunter it must have the advantage of a variety of movements when in pursuit of its prey. Its shoulder blades are aligned with the side of its body, and it has only a vestigial collarbone, so its shoulders are able to move quite freely, which increases the length of the running stride. During walking, as the forelimbs are placed down on the ground this has a naturally retarding action on the pace, but when running fast, nearly all that effect is lost the cat extends its forelimbs and arcs down and back before contact is made with the ground. The flexible arching of the cats spine allows it to extend its stride further by several centimetres.

When a cat is running and galloping the legs are used together in turn on each side of the body. When in full gallop the cat is airborne for most of the extended stride, without any paw touching the ground. When landing between airborne bounds, its forepaws are overtaken by its hindpaws.

RELATED AREAS

2 Jumping

Cats are renowned for their wonderful jumping ability and can leap several times their own length either vertically or horizontally. Their amazing accuracy when landing on a narrow ledge or the top of a fence after a jump is in part thanks to the time that they take to assess it beforehand.

How a cat jumps

When a cat jumps, whether onto a table, branch or prey, it first takes all its weight onto its hindlimbs, and it is the extension of these that propels its leap. The back and hindquarter muscles are extremely strong and they give the cat its tremendous power to jump up, down, and over a gap or obstacle.

Although a cat has great jumping skills, it needs a firm surface from which to make its leap. It will take some time to size up the jump and will also carefully test the firmness of the take-off with its hind feet, before making a perfectly judged leap. This patient assessment is crucial when the landing place is small or narrow, for example a shelf, windowsill or tree branch, or the gap to be cleared is wide. It is also important when the cat pounces on its prey: here, the judgement is of where the moving prey will be when the cat lands.

RELATED AREAS

3 Balancing act

The cats tail is incredibly versatile. It is of particular value in the balance of tree-climbing cats, but also acts as a gyroscopic counterweight when cats corner suddenly after prey, which can be seen most readily in the cheetah, the fastest cat. The tail is also a signalling system and can be fluffed, twitched or wagged to indicate fear, indecision or aggression.

How cats fall on their feet

The cats design and build is that of a woodland hunter. Cats move effortlessly among tree branches, aided by the balancing movements of their tail. If their balance is threatened, the tail comes into play. Should they fall, cats have a remarkable ability to land on their feet, which they do by rotating their bodies in mid-air. This is a reflex action and it appears in the kitten in the third week of life, as the youngsters mobility increases.

What happens is this as the cat falls through the air, it first rotates its head and the front half of its body, until its head has achieved the correct orientation. It then rotates the back end of its body, allowing it to land safely on its feet. The cat is able to carry out this manoeuvre due to its finely attuned sense of balance, which comes from its eye sight and canals in the inner ear (see ).

It is this same fine sense of uprightness and movement that feeds the cat information on its posture during the dramatic changes of position which take place in the course of a hunt or a fight.

RELATED AREAS

4 Cats eyes

The eyes are one of the keys to understanding the relationship between cat behaviour and structure. As befits a hunter, the eyes face forward and so, like us, the cat has good three- dimensional and distance evaluation. The all-round vision of herbivorous species allows predators to be seen but lacks the advantages of binocular vision.