TWO INNOCENTS IN RED CHINA

translated by

I.M. OWEN

PIERRE TRUDEAU

JACQUES HBERT

with a new introduction and afterword by

ALEXANDRE TRUDEAU

DOUGLAS & MCINTYRE

Vancouver/Toronto

Main text copyright 1961, 2007 by Jacques Hbert and Pierre Elliott Trudeau

Translation Douglas & McIntyre Ltd. 2007

Introduction and afterword 2007 by Alexandre Trudeau

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The

Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence,

visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Douglas & McIntyre Ltd.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada V5T 4S7

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-55365-254-0 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-55365-380-6 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-926706-93-1 (ebook)

Introduction and afterword edited by Scott Steedman

Jacket design by Peter Cocking & Naomi MacDougall

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the

Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council,

the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit,

and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing

Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities.

CONTENTS

by Alexandre Trudeau

1 | IN WHICH THE EXPEDITION

NEARLY SINKS IN THE THAMES

3 | FROM THE PEOPLE S PALACE

TO THE PALACE OF THE EMPERORS

11 | INDUSTRY AND CULTURE

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE

14 | FROM THE EMPTY

CATHEDRAL TO THE CHILDRENS PALACE

by Alexandre Trudeau

TWO INNOCENTS IN RED CHINA

BY ALEXANDRE TRUDEAU

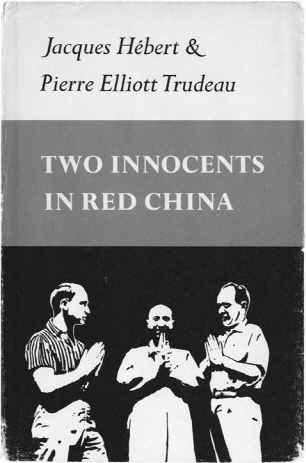

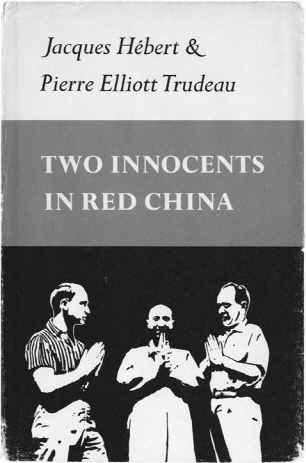

I was born to one of the authors of Two Innocents in Red China. I guess it is fair to say that I have always known about this book. Deep in the murky depths of my childhood memories, I remember, of all the things that might have impressed me about my father, being very impressed that he had written a book. How grand and mighty it seemed that my father had his name printed in large letters on the cover of an actual book. I have no memories of any other books that he had written, just this one. Perhaps I remember it because it was colourful and old-looking and even featured a picture of him on the cover. Perhaps because it had an odd title that I never really understoodwho were these Innocents, anyway? Or perhaps it was because he had written the book with a friend, Jacques Hbert, who stood near him smiling in the photo, and the very idea that my father had friends like I did struck me as strange and somehow incomprehensible. Perhaps I remember that book because it was about China. Red China. And I knew about China. Though I was puzzled by the word red.

China is one of the first countries that I ever learnt about. Canadian children learn about China in the sandbox; it is the place that you will reach if you dig deep enough. They also learn about China when they find out what a billion is. There are a billion people in China, they are told. A billion people! My personal mythology linked me to China in another way as well. The idea of China as a place always accompanied that strange explanation that I had once been inside my mothers belly. I was told that I had been in my mothers belly while she was in China. That is quite a thought for a small child: in the belly in China! I later learnt that my parents had indeed visited China in October 1973; I was born in December.

I also remember that when my brothers and I were quite young, before we had started to accompany my father on official trips, he was gone for a whole month on a trip to China. To Tibet, in fact. It was the longest time that he had been away since we were born. We asked him why he was going to Tibet, and he replied that he was going because he had never been there before. What a mysterious answer that was! Maybe we too would go to Tibet some day, because we certainly hadnt been there either. My father told us that Tibet was the place where the Himalayas were. They were the highest mountains in the world. It was also the home of the Yeti, a.k.a. the Abominable Snowman, and the land of Shangri-La, the most beautiful place in the world. At our cottage, we had an old map of the world on the wall, and my father pointed Tibet out to us. Under the name were parentheses and some script that said, Occupied by China since 1951. What did that mean? I asked. He told us that Tibet was part of China. But that it hadnt always been.

Because it was his first trip away from us that I can remember, my fathers journey to Tibet fascinated me. It was not so much the place that stuck in my head but the fact that he had gone away, as far away as a place called Tibet, in China, where the mountains are. We waited for him and grew ever more excited as his return approached. And when, as predicted, he did indeed return, he looked and smelt different, which we hadnt expected at all. He had a beard and a tan, and a strange energy about him. He radiated a kind of power, seemed more aggressive and alive than usual. It was as if his eyes still reflected the sights that he had seen, as if his body was still poised to meet them head on. This was a new father, not the patient and adoring father but the free spirit who had wandered the world. The lone traveller. The observer of things. The holder of secret knowledge. He brought with him a series of elaborately painted papier mch masks and painted wooden swords from the Chinese opera.

For the first time, I began to understand what travelling was: going far away to places one had never visited but somehow needed to go to, and then returning home with strange and wonderful things, somehow changed, both inside and out. I had begun to grasp what my father meant when he said that he had travelled around the world and been to a hundred countries. More importantly, I had begun to understand why one travels. And, in my mind at least, I had begun to become a traveller myself. China became inextricably linked to travel.

Next page