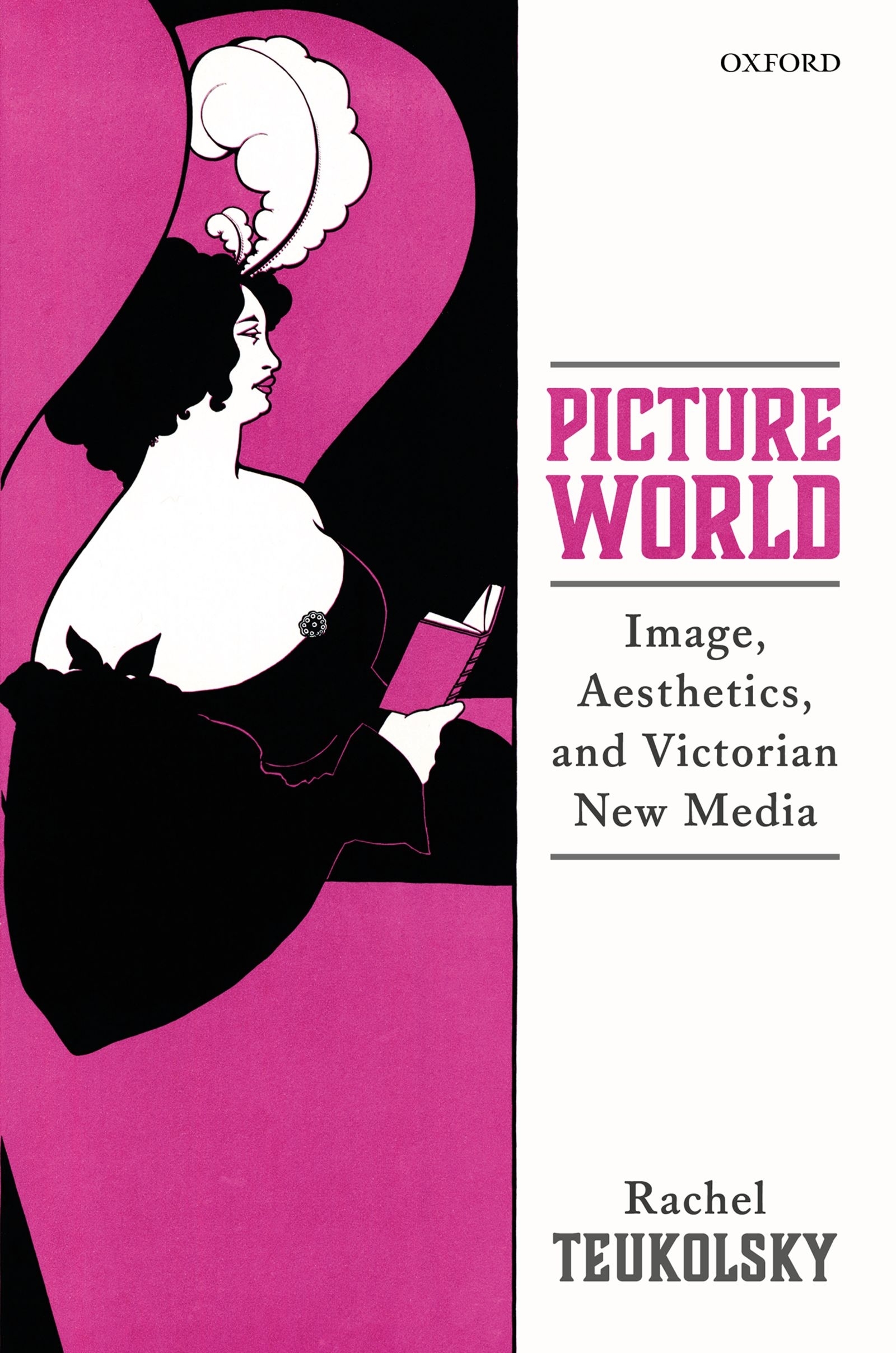

Teukolsky Rachel - Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media

Here you can read online Teukolsky Rachel - Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Oxford University Press USA - OSO, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxford University Press USA - OSO

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Rachel Teukolsky 2020

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2020

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935624

ISBN 9780198859734

ebook ISBN 9780192603579

Printed and bound by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Generous friends and colleagues helped to shape this book over many years. Susan Zieger read most of the manuscript and spurred me on with her brilliance and fire. Matt Potolsky also read many chapters and applied his keen intelligence to help me rethink many things. Individual chapters were read, some long ago and some more recently, by Rachel Ablow, James Eli Adams, Jo Briggs, Jay Clayton, Nick Gaskill, Lauren Goodlad, Rae Greiner, Daniel Hack, Ivan Krielkamp, Richard Menke, Sebastian Lecourt, Andrew Miller, Daniel Novak, Morna ONeill, and Dahlia Porter. Key conversations also took place with Elaine Auyoung, Brenda Cooper, Colin Dayan, Elaine Freedgood, Scott Juengel, Grace Lavery, Sara Maurer, Ashley Miller, Benjamin Morgan, Cannon Schmitt, and Jonah Siegel. These lists dont include all of the people who asked me questions at lectures or conferences, or who came up to me in the hallway of a conference hotel with important additional insights. It seems impossible to acknowledge everyone who contributed to the effort. Im grateful for the wonderful community and web of influences that helped me to complete the project. The wisdom of my interlocutors continues to amaze me.

Thanks are due to the institutions that helped to support this writing and research. Yale University and the Beinecke library provided a James E. Osborne Postdoctoral Fellowship; the National Endowment for the Humanities granted a Summer Stipend; and Vanderbilt University conferred a Chancellors Faculty Fellowship as well as additional funds to support the costs of image reproduction.

Certain collectors kindly donated images from their personal collections and allowed these to be reproduced in the book. Thank you to Mike Ashworth, Andrew Gasson, Peter Stubbs, and Beverly and Jack Wilgus. Ray Norman at the World of Stereoviews, UK, provided additional help in tracking down images. At Vanderbilt, a heartfelt thank-you to the library and image specialists who worked painstakingly to create a number of the books illustrations: Jamie C. Adams, Philip Nagy, Nathan Jones, and Teresa Gray, Curator of Special Collections. Jennifer Fay spent time showing me how to acquire screen grabs from the old films discussed in the books conclusion. Sari Carter, a former Vanderbilt PhD, devoted her usual tenacity to checking all of the citations. At Oxford University Press, Jacqueline Norton and Aimee Wright applied enthusiasm and skill in transforming the manuscript into a book.

Thanks to Duke University Press, Indiana University Press, and De Gruyters for permission to reproduce previously published work. Material from appeared as Stereoscopy and the Global Picturesque, in Traveling Traditions: Nineteenth-Century Negotiations of Cultural Concepts in Transatlantic Intellectual Networks, ed. Erik Redling (Berlin: De Gruyter Press, 2016), 189212.

Im grateful to my familyparents Roselyn and Saul, sister Lauren, brother-in-law Josh, nephews Noah and Jacobfor their animated support over the years.

Finally, thank you to the dear ones who helped me to live, and showed me how: Danielle Wasserman, Nancy Reisman, Lee Conell, Alex Trevisan, Lincoln Holdaway, Dan Altman, Hilary Cloos, Chris Hernandez, Sebastian Conley, Alex Gross, Ben Brill, Josh Sallo, Chris Reagan, and Caleb Stapleton. You have made as it were, for the human body a soul of waters, for the human soul a body of flowers. Thank you.

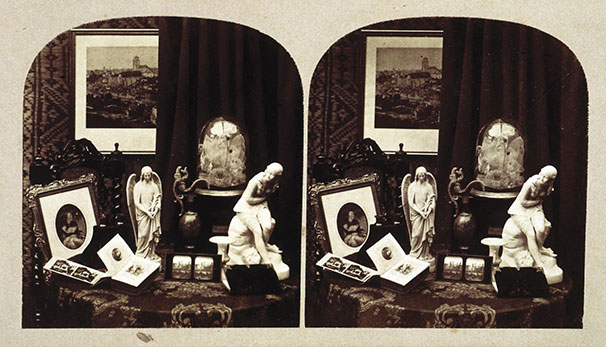

A photograph held in the Victoria and Albert Museum opens onto the idealized world of the Victorian parlor (

Fig. 0.1 Unknown artist, Still Life. Stereographic photograph. Albumen print mounted on glass, c. 186070. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Benjamin theorized the parlor as an insular refuge from the chaos of urban modernity, an upholstered, curtained shell devoted to protective self-fashioning. Yet the parlor was not quite the hermetic casing that Benjamin envisioned, I will suggest here, nor was it a site of mere idle luxury. With its profusion of visual objects, the parlor can also be seen as a portal. It was home to the picture-world of the nineteenth century, in the form of the mass-printed photographs, advertisements, cartoons, and illustrationsephemeral and often disposablethat flourished in the era of mechanical reproduction. These alluring objects were miniaturized spectacles that served as portals onto phantasmagoric versions of the world. In the world-interactive site of the parlor, mediating between private and public, families received visitors and displayed objects as evidence of a certain cosmopolitanism: maps, globes, cabinets of stereographs with views of faraway places, an illustrated Bible on a stand with scenes from the Holy Land, illustrated newspapers and magazines on a table, prints and portraits on the wall depicting figures from religious and political history. This thought indicates a more permeable sense of the parlors enclosure, phantasmagoric but also scopic, opening onto a series of shifting views. The illustrated Bible serves as an exemplary object to anchor this space, as it mediated between tradition and modernity, the near and the far, the rare and the popular. Many of the multiform works of new Victorian visual media opened onto worlds-within-the-world, animating fantastical leaps across space and time while concretizing and literalizing a Victorian world picture.

This book studies the modern media world as it came into being in the nineteenth century. Machines were harnessed to produce texts and images in unprecedented numbers; in the visual realm, new industrial techniques generated a deluge of affordable pictorial items, consumed at intimate scale. These early forms of a widely shared media culture transformed the nineteenth-century experience of everyday life. New media today might bring to mind cyberspace, hypertext, and other digital innovations. But media invention itself is not new, and every epoch has had to confront the unruly and transformative effects of new communications technologies.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media»

Look at similar books to Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.