For Ruth. Thank you for your friendship and your passion for the ocean.

Text copyright 2020 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

An imprint of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com.

Main body text set in News Gothic Com Roman.

Typeface provided by Linotype AG.

Names: Peterson, Christy, author. | Twenty-First Century Books (Firm)

Title: Into the deep : science, technology, and the quest to protect the ocean / Christy Peterson.

Description: Minneapolis : Twenty-First Century Books, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Audience: Ages: 1318. | Audience: Grades: 9 to 12.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019020685 (print) | LCCN 2019981277 (ebook) | ISBN 9781541555556 (library binding : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781541583849 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ocean. | Oceanography. | Marine ecology. | Marine biology. | Marine resourcesManagement. | Restoration ecology. | Underwater exploration. | Climate change mitigation.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank the generous scientists, researchers, and technicians who made this book possible by patiently explaining their work and answering the endless questions of an enthusiastic layperson. Without them, this book would not have been possible. Any mistakes are my own.

Megan Scanderbeg, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, California

Emery Nolasco, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, California

Jennifer B. Paduan, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, California

Dr. Eleanor Frajka-Williams, National Oceanography Centre, UK

Jonathan Peter Fram, Oregon State University, Oregon

Dr. Jack Barth, Oregon State University, Oregon

Flora Vincent, PhD, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel

Dr. Petra H. Lenz, University of Hawaii at Mnoa, Hawaii

Dr. Vittoria Roncalli, University of Barcelona, Spain

Dr. Eva Majerov, University of Hawaii, Hawaii

Larry Hufnagle, NOAA NWFSC, Washington

Dr. Kim Martini, Sea-Bird Scientific, Washington

Dr. Tracey Sutton, Nova Southeastern University, Florida

Nina Pruzinsky, Nova Southeastern University, Florida

Dr. Rupert Collins, University of Bristol, UK

Dr. Leigh Torres, Oregon State University, Oregon

Dr. Maureen H. Conte, Marine Biological Laboratory, Massachusetts

Dr. Rut Pedrosa Pmies, Marine Biological Laboratory, Massachusetts

J. C. Weber, Marine Biological Laboratory, Massachusetts

Dr. Andrew Shao, University of Victoria, Canada

Additional thanks to Ruth Musgrave, Robert Tuck, and my familyI couldnt have done it without you.

Introduction

O n January 21, 2018, a woman walking along a sandy beach in Western Australia noticed a dark brown bottle partially buried in the sand. Thinking it might make a unique decoration for her home, she retrieved it and showed it to her family. The discovery proved to be more intriguing than expected. Inside the bottle, covered in damp sand, lay a tightly wrapped roll of paper secured with twine.

The family feared that unwrapping the damp paper might damage the document, so they dried it in the oven. Then they carefully unrolled it to reveal the contents: a combination of typeset and handwritten text. Written in German, the preprinted portion included instructions to ship the bottle back to the German Naval Observatory in Hamburg. The handwritten section recorded the ships name, the Paula ; the ships home port, Elsfleth; its port of departure, Cardiff; and its destination, Makassar. It also noted the location where the bottle went overboard. But the most surprising portion of the message was the dateJune 12, 1886.

Was the bottle a fantastic piece of history or just an elaborate hoax? The family turned to the Western Australian Museum for assistance. The museum discovered that the bottlea gin bottle made in the Netherlandsdid indeed date from the late nineteenth century. And experts in Germany confirmed that a ship named Paula set sail from Cardiff bound for Makassar in 1886. They located the ships meteorological journal, which contained an entry for June 12, 1886, noting the deployment of a drift bottle. The handwriting in the journal exactly matched the paper found in the bottle.

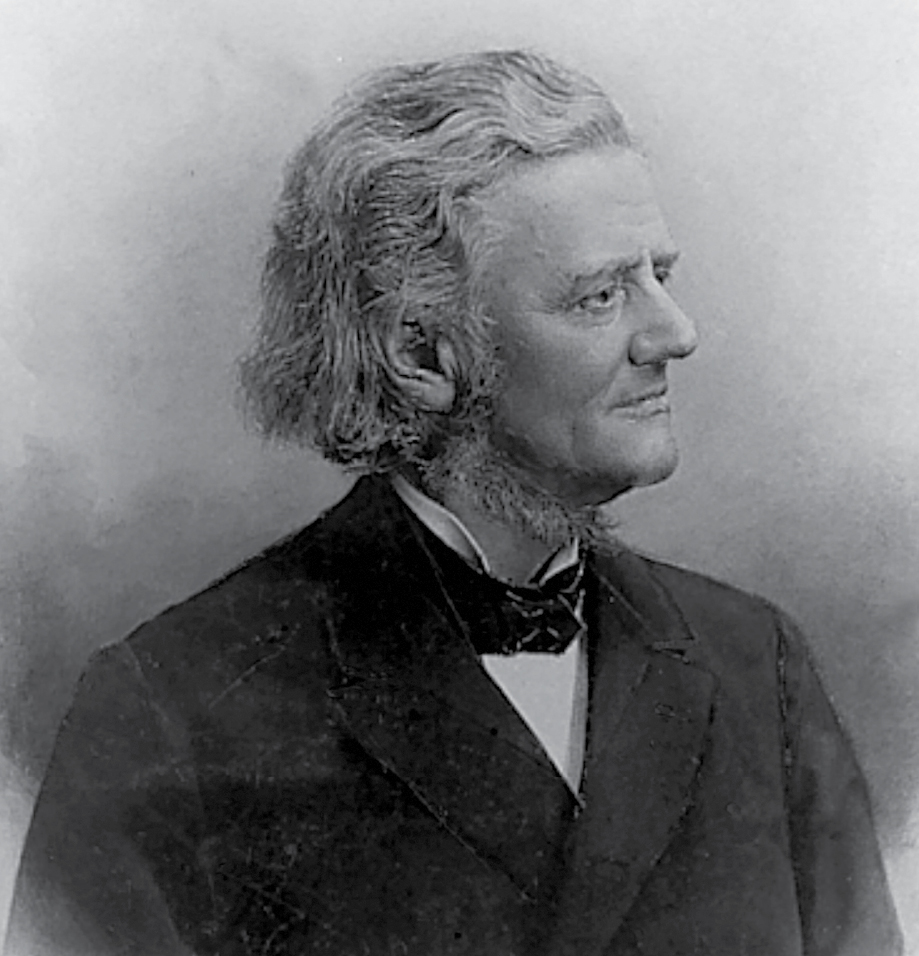

The experts determined that the bottle had been part of an experiment conceived by German scientist Georg von Neumayer, who wanted to know more about ocean currents. He hoped this research would help shipping companies move goods around the world more efficiently. Beginning in 1864, commercial ships deployed more than 6,000 bottles. Of those, 662 eventually found their way back to Germany. The 663rd bottle, found in 2018, is on loan to the Western Australia Museum.

Scientist and explorer Georg von Neumayer (18261909), who was born in Germany and spent much of his life in Australia, was proponent of international collaboration and cooperation in scientific endeavors.

Von Neumayer was not the first to throw bottles overboard to study ocean currents. The earliest known drift bottle study occurred in 310 BCE when Greek philosopher Theophrastus tossed sealed bottles overboard to prove that water flowing in from the Atlantic Ocean had formed the Mediterranean Sea. However, the German study coincided with the earliest days of a new area of science: oceanography. The bottle unearthed on an Australian beach 132 years after it was tossed overboard was part of an early attempt to understand the ocean in a new way.

Tech Focus: NOAA Drifters and Argo Floats

Scientists continue to use drift bottle studies, but they have significant limitations. Only a small percentage of the bottles find their way back to researchers. They also only record two data points: where they started and where they ended up. Because most bottles float, winds influence their movement much more than surface currents do. In the middle of the twentieth century, scientists began developing more sophisticated bottles that could be reliably tracked and record far more data. They resulted in two new kinds of tools that expand upon Georg von Neumayers efforts.

Drifting buoys, or drifters, bob along like a glass bottle, but that is where the similarity ends. A drifter has a long, cylinder-shaped tail. This allows the buoy to move with ocean currents below rather than with the winds above. The drifter includes scientific instruments that record location as well as barometric pressure, temperature, salinity, and other details about the waters chemistry. Data are uploaded to satellites.