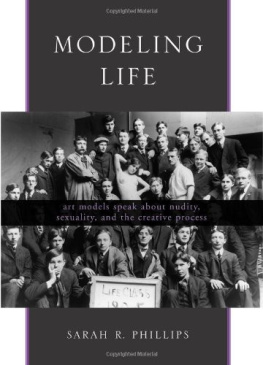

MODELING

LIFE

art models speak about nudity,

sexuality, and the creative process

S A R A H R. P H I L L I P S

Modeling Life

This page intentionally left blank.

M O D E L I N G L I F E

Art Models Speak about Nudity,

Sexuality, and the Creative Process

SARAH R. PHILLIPS

S TAT E U N I V E R S I T Y O F N E W Y O R K P R E S S

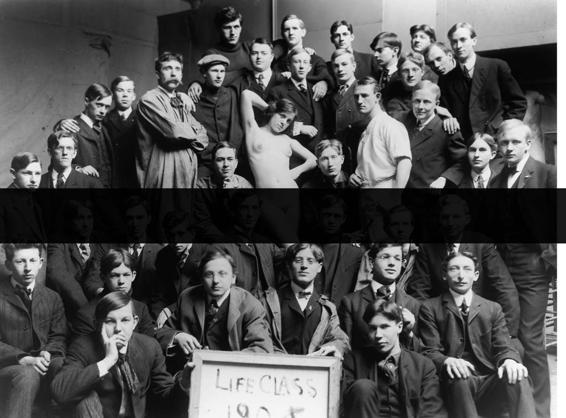

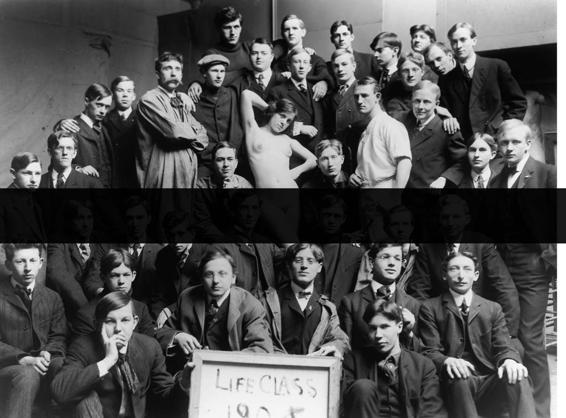

Cover: 1905 Life Modeling Class, Art Institute of Chicago, photo archives of Alex Blendl.

Photos of life drawing classes by David Friedman.

Published by

State University of New York Press

Albany

2006 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, address

State University of New York Press

194 Washington Avenue, Suite 305, Albany, NY 12210-2384

Production, Laurie Searl

Marketing, Fran Keneston

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Phillips, Sarah R., 1963

Modeling life : art models speak about nudity, sexuality, and the creative process p>

Sarah R. Phillips.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7914-6907-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-7914-6907-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-7914-6908-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-7914-6908-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Artists models. 2. Artists models

OregonPortlandAttitudes. I. Title.

N7574.P47 2006

702.8dc22

2005037172

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Preface

vii

Acknowledgments

ix

One

Assuming the Pose: An Introduction to

Life Modeling

Life Models

Aesthetic Fashion and the Profession of

Life Modeling

Contemporary Life Modeling in the

United States

Two

Returning the Gaze: Objectification and the Artistic Process

What Is Art?

The Model as Object

The Model as Agent

The Particular Case of Photography

Three

Stephen

Four

Defining the Line: Sexual Work versus Sex Work 35

Cooperative Interaction in the Art Studio

Separating Sexual Work from Sex Work

Establishing That Serious Work Is Happening vi

CONTENTS

Five

Maintaining the Line: Coping with Challenges to the Serious Work Definition

Challenges to the Serious Work Definition

Six

Denise

Seven

Modeling Gender: Social Stigma, Power,

and the Penis

Social Stigma

Power and Vulnerability

Safety

Gender and Erotic Experience while Posing

Eight

Michael

Nine

Irene

Ten

Being Present: Getting Good at It

From Whimsy to Intention

The Good Life Model

Being Committed

Research Notes

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Preface

Since beginning my work with life models, the question that Ive been asked most frequently is: How did you get interested in doing research on that? The voices of the people asking suggest that they expect to hear a titillating story. Most people, Ive discovered, have a romantic and sexual picture of what goes on between a life model and an artist in a studio. They picture a young, female model and an older, male painter. They picture the painter gradually seducing his nave model in some made-for-Hollywood sexual awakening story. As is so often the case, the truth is much more mundane.

I began thinking about life models while I was completing my postdoc-toral appointment. At the time, I taught criminology courses for the Department of Sociology at Yale University, including one very large class of undergraduates. The class met Tuesday and Thursday mornings, and on Tuesday evenings, I attended figure-sculpting classes. Not an artist, I was taking beginning sculpting classes as a way to relax in the evenings. Midway through my second term, the figure sculpting class began working with a new model, a young woman who would be posing nude for the class for the next five weeks.

I noticed nothing unusual about this model as she discarded her robe and assumed a reclined pose. About fifteen minutes into the session, however, the model changed her pose, and we happened to make eye contact. It was then that I realized I knew her: earlier that day, she had been taking notes in the front row of my criminology lecture.

For the first time, I felt awkward and embarrassed. I was no longer looking at a nude model, I was looking at one of my students naked, a student to whom I would have to assign a grade in just a few weeks. In retrospect, this need not have been a problem if I had simply confronted the awkward situation and discussed how to handle it. Instead, I responded with striking immaturity: I never returned to my figure sculpting class, and the model/student moved her seat to the very back row of the lecture hall. Neither of us ever said a word about it.

vii

viii

PREFACE

What had suddenly turned my nude model into a naked girl? How had my artists gaze transformed instantly into that of the voyeur? And what was a Yale student doing undressing for money, anyway? This book represents the culmination of the research journey sparked by these questions. Over a ten-year period, I have read about models, interviewed current and former models, and spent countless hours watching life models work in schools and studios. I am not a life model, and I do not presume to speak for all life models.

Nor am I an artist. My husband, David Friedman, is an artist, but with the exception of taking the photographs for this book, his work has not taken him to the life studio for many years. There are many fine works about artists, their practices, and how we typify both artists and the artistic endeavor. In this book, I have not sought to portray the artists perspective. I have, instead, focused my attention narrowly on contemporary life models in the Western art tradition. Unlike artists, life models have rarely been asked to explain their work. In this book, I have tried to give them a chance to speak for themselves and in their own words.

Acknowledgments

The earliest stages of this research were supported by small grants from The Foundation for the Scientific Study of Sexuality and a Meyer Grant from Pacific University. I am grateful to the University for providing me with sab-batical funding so that I could complete this project.

My thanks to Nancy Ellegate, senior acquisitions editor at State University of New York Press, for her continued interest in my project, and Laurie Searl, senior production editor, for her patient guidance.

Over the course of ten years, several Pacific University undergraduate students helped with parts of this project. In particular, I appreciate the many hours of tedious transcription done by Lalea Dolby, Laurel Martin, and Anne Sinkey.

These students occasionally helped with interviews and presentations as well.

I am grateful to my husband, David Friedman, and friend Dan Kvitka for their photography and help in preparing images for this book.

My parents, Joan and Rich Phillips and Kay and Howard Friedman, and my sisters, Kate and Liz, have followed the long path of this work. I am always appreciative of my familys love. My sister Kate Phillips, a writer herself, spent many hours reading and editing drafts. She, especially, has given me unwa-vering kindness and encouragement over the years.

Next page