DEADLY COMPANIONS

DEADLY COMPANIONS

How Microbes Shaped Our History

DOROTHY H. CRAWFORD

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6 DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York

Auckland CapeTown Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Dorothy H. Crawford 2007

The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

978-0-19-280719-9

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

Figures and Tables

FIGURES

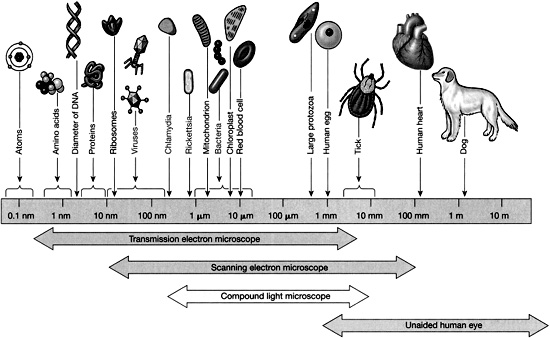

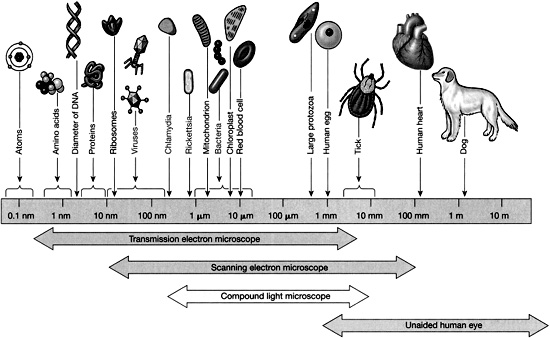

Relative sizes of organisms and their component parts

SARS in Hong Kong

Incidence of West Nile fever in the USA, 19992004

Ro: the basic reproductive number of an epidemic

Malaria parasite life cycle

Notification of measles cases in UK from 1963 to 1976

Drawings from the Ebers papyrus possibly depicting haematuria caused by schistosomiasis

An illustration of a penile sheath worn in Ancient Egypt, circa XIX Dynasty. 13501200 BC

Schistosomiasis: transmission cycle of Schistosomiasis mansoni

Map showing the advance of the Black Death

Map of present day plague foci worldwide

Plague cycles

Title page from Bartholomew Stebers Syphilis, 1497 or 1498

Cholera: a map showing its pandemic spread, 195994

Cholera: the natural and epidemic cycles of Vibrio cholera

A section of a leaf showing the potato blight fungus growing and producing spores (Berkley 1846)

Population growth, 8000 BC AD 1974

MRSA in England and Wales, 19892004

Worldwide distribution of TB

Geographical distribution of malaria worldwide.

The emergence of pandemic flu virus strains after reassortment in a pig

TABLES

Ro values for human and animal microbes

Examples of species domesticated in different areas of the world

A sample of human pathogens which have emerged since 1977

Preface

Microbes first appeared on planet Earth around 4 billion years ago and have coexisted with us ever since we evolved from our ape-like ancestors. By colonizing our bodies these tiny creatures profoundly influenced our evolution, and by causing epidemics that killed significant numbers of our predecessors they helped to shape our history. Through most of this coexistence our ancestors had no idea what caused these visitations and were powerless to stop them. Indeed the first microbe was only discovered some 130 years ago and since then we have tried many ingenious ways to stop them from invading our bodies and causing disease. But despite some remarkable successes, microbes are still responsible for 14 million deaths a year. In fact new microbes are now emerging with increasing frequency, while old adversaries like tuberculosis and malaria have resurged with renewed vigour.

This book explores the links between the emergence of microbes and the cultural evolution of the human race. It combines a historical account of major epidemics with an up-to-date understanding of the culprit microbes. Their impact is discussed in the context of contemporary social and cultural events in order to show why they emerged at particular stages in our history and how they caused such devastation.

We begin with SARS, the first pandemic of the twenty-first century. Then we travel back in time to the origin of microbes and see how they evolved to infect and spread between us with such apparent ease. From there we follow the interlinked history of man and microbes from the plagues and pestilence of ancient times to the modern era, identifying key factors in human cultural changes from hunter-gatherer to farmer to city-dweller which made us vulnerable to microbe attack.

The final chapters show how modern discoveries and inventions have impacted on todays global burden of infectious diseases and ask how, in an ever more crowded world, we can overcome the threat of emerging microbes. Will pathogenic microbes be conquered by a fight to the death policy? Or is it time to take a more microbe-centric view of the problem? Our continued disruption of their environment will inevitably lead to more conflict with more microbes, but now that we appreciate the extent of the problem surely we can find a way of living in harmony with our microscopic cohabitants of the planet.

Throughout this book the term microbe is used for any organism that is microscopic, be it a bacterium, virus, or protozoan (do seem to lie in wait for a suitable host and then jump, attack, invade and target. Although these descriptions seem apt and are frequently used in the text of this book to illustrate the lives of microbes, in reality microbes are not capable of malice aforethought.

Figure 0.1 Relative sizes of organisms and their component parts

Source: J. G. Black, Microbiology, Principles and Exploration, 5th edn 2002, Fig. 3.2; reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Wherever possible the scientific terms used in the book are defined in the text, but there is also a glossary at the end which provides additional information.

Acknowledgements

This book could not have been written without help and support from many people to whom I am extremely grateful. In particular I thank my editor, Latha Menon, for her help and encouragement, and the following colleagues for providing expert information and advice: Professor Sebastian Amyes (antibiotic resistance), Dr Tim Brooks (plague), Dr Helen Bynum (historical events), Professor Richard Carter (malaria), Dr Gareth W Griffith (potato blight), Professor Shiro Kato (smallpox in Japanese cultural history), Dr Francisca Mutapi (schistosomiasis), Dr G Balakrish Nair (cholera), Professor Tony Nash (flu), Dr Richard Shattock (potato blight), Professor Geoff Smith (smallpox), Dr John Stewart (bacteria), Dr Sue Welburn (trypanosomiasis), Professor Mark Woolhouse (epidemiology). In addition I am grateful to the following for reading and commenting on the manuscript: Danny Alexander, William Alexander, Martin Allday, Roheena Anand, Jeanne Bell, Cathy Boyd, Rod Dalitz, Ann Guthrie, Ingo Johannessen, Karen McAulay, J. Alero Thomas.

Next page