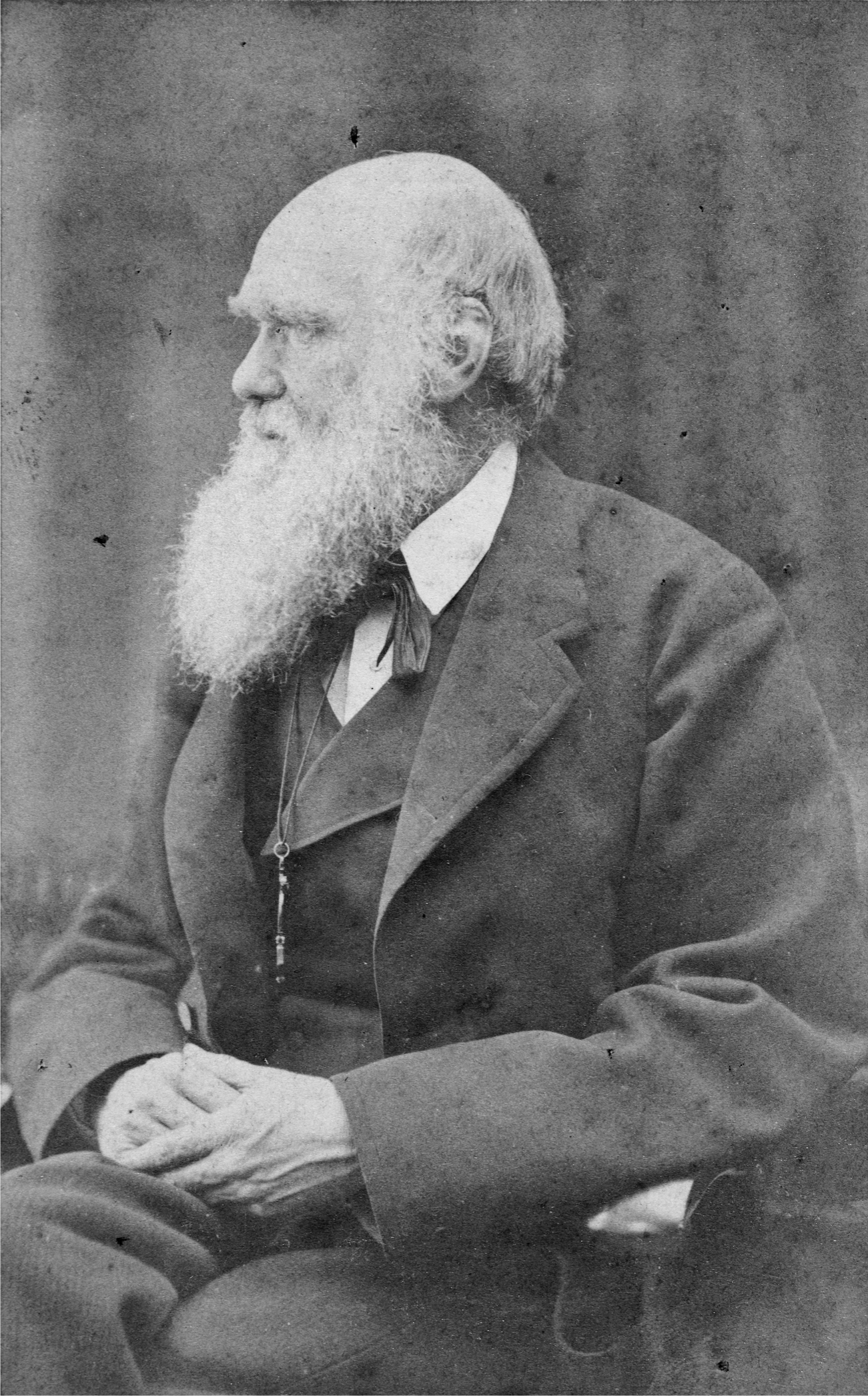

. Charles Darwin in 1871

. Gibraltar Neanderthal skull

.Australopithecus skull and reconstruction

PREFACE

ON A COLD AND DRIZZLY February afternoon, I walked from bustling Euston Station to 4 Chester Place Road, a luxurious, cream-colored three-story, five-bedroom flat with large windows facing west toward the greenery of one of Londons royal parks. I didnt knock, knowing of course that Sarah, Emma, or Charles would not be there to answer. For several minutes, I stared up at the large second-floor windows, trying to imagine the scene a century and a half earlier when Charles Darwin held in his hands, for the first and only time, the ancient fossilized skull of an extinct human.

From August 25 to September 1, 1864, the resident of 4 Chester Place Road, Sarah Elizabeth Wedgwood, hosted her younger sister Emma Darwin and Emmas husband, Charles. Charles had been quite ill, and the Darwins had traveled from their country home at Downe, in Kent, to stay for a week to, as Charles wrote, see how I stand a change.

The Wedgwood flat was in the perfect location for Charles. It was about a kilometer from the home of geologist Charles Lyell, a close friend and colleague of Darwins, and within walking distance to the botanical gardens maintained by the Royal Botanical Society and the Zoological Society of London. It would be a good place for Charles to rest his body while keeping his mind active as he finished his manuscript on climbing plants. As he wrote at the end of 1864, I have suffered from almost incessant vomiting for nine months, & that has so weakened my brain, that any excitement brings on whizzing & fainting feelings.

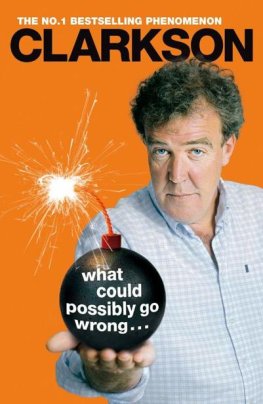

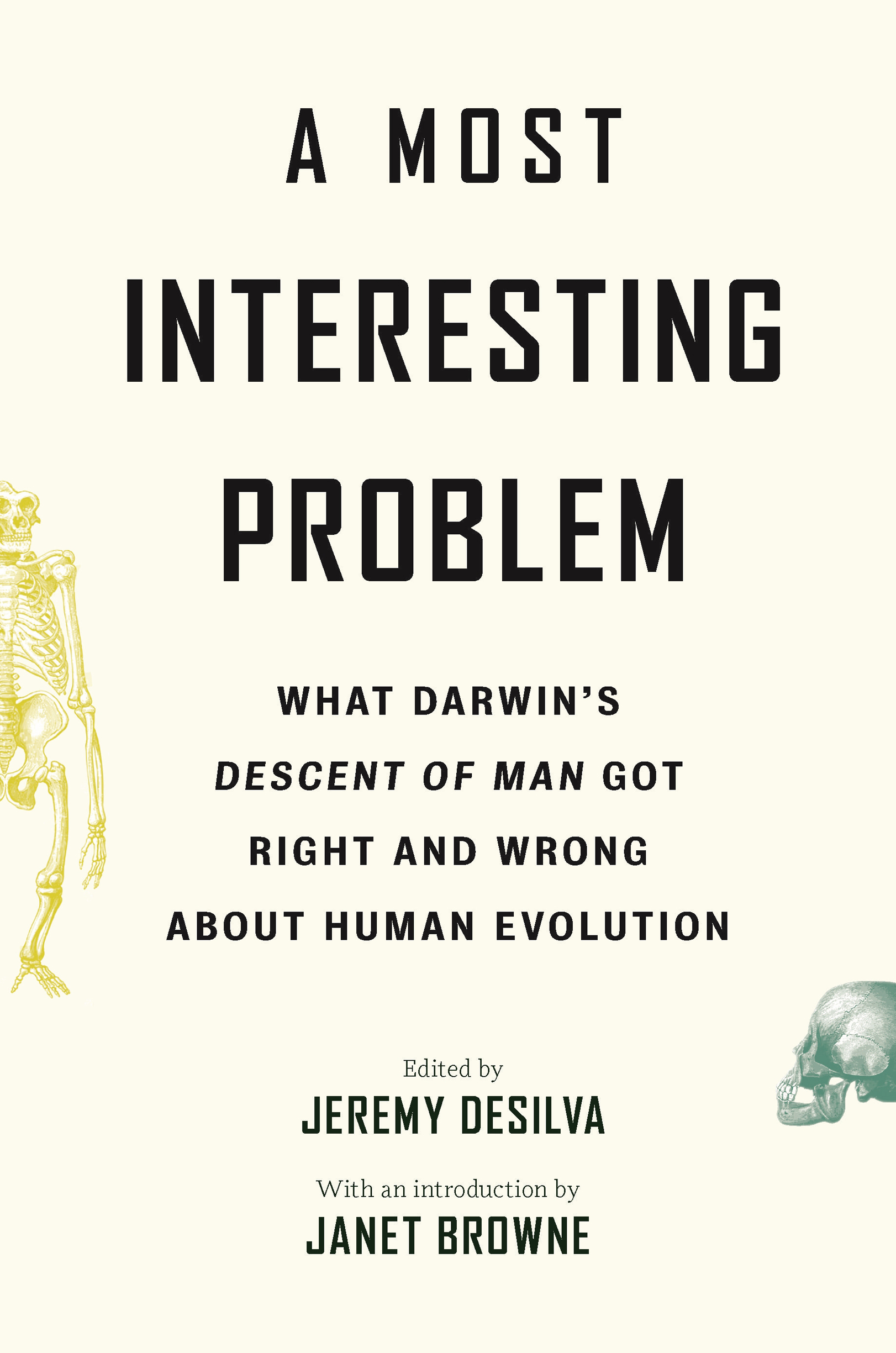

The unusual fossilized skull brought to Darwin in the summer of 1864 had been discovered in Forbes Quarry, Gibraltar, in 1848 (see

What is remarkable about this event is just how small an impact this fossil skull had on Darwin. The only evidence that this meeting occurred at all is a throwaway line in a September 1, 1864, letter Darwin wrote to Joseph Dalton Hooker when he returned to Down House. Both Lyell & Falconer called on me & I was very glad to see them. F. brought me the wonderful Gibralter [sic] skull.Farewell. Ever Yours | C. Darwin, he wrote to his good friend on a Thursday evening. Falconer himself recorded nothing about the meeting and died just five months later. If Darwin made sketches of the skull or jotted down any notes, they are lost.

As a paleoanthropologist who studies the human fossil record, I find this unsettling. How could the great Charles Darwin hold this skullrecognized today as a female Neanderthaland not see, with his legendary observational skills, the significance of it?

As I looked up into the windows of 4 Chester Place Road, I imagined Darwin holding the ancient skull. He turns it with delicate hands and stares into the large, round eyes of the Gibraltar Neanderthal, rubbing his thumb against the thick, double-arched brow ridges. He marvels at the enormous size of the nasal cavity. Upon turning the skull to the side, he remarks to Falconer how the skull sweeps back and lacks the tall forehead of a modern human. Falconer reminds Darwin that just a year earlier, at the British Association for the Advancement of Science meeting, William King had presented evidence based on a partial skeleton from Feldhofer Cave in Neander valley, Germany, for an extinct population of Europeans he called Homo neanderthalensis. One odd skull can be dismissed. But two? Two is a pattern, I imagine Darwin saying with a smile.

But probably none of that happened.

PREFACE. Gibraltar Neanderthal skull. ( Chris Stringer/The Natural History Museum, London)

It is more likely that Darwin thanked Falconer for coming and apologized for his ill health, which had made him weak, unfocused, and at times depressed. Perhaps in this state, he could not focus on the Gibraltar skull without feeling faint and instead made a few cursory observations before carefully handing it back to Falconer.

Perhaps too it was difficult for Darwin to see the details of the Gibraltar skull that are so compelling to paleoanthropologists today. In 1864, the skull still had not been fully cleaned of its rocky matrix. The details of the nasal cavity, for instance, were obscured by cemented sand. Or maybe he did study it carefully but recalled Thomas Henry Huxleys observations of the skull from the Feldhofer Cave. Huxley, whom Darwin trusted on matters related to human anatomy and evolution, wrote just a year earlier, in