Darwins Dogs

How Darwins pets helped form a world-changing theory of evolution

Emma Townshend

First published in 2009

by Frances Lincoln Ltd, 7477 White Lion Street, London N1 9PF

www.franceslincoln.com

This e-book edition first published in 2014

Darwins Dogs

Text Copyright Emma Townshend 2009

Illustrations As listed opposite

All rights reserved

This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN TBC

Design: www.williamhall.co.uk

Digital edition: 978-1-78101-172-0

Softcover edition: 978-0-71123-065-1

Darwins Dogs

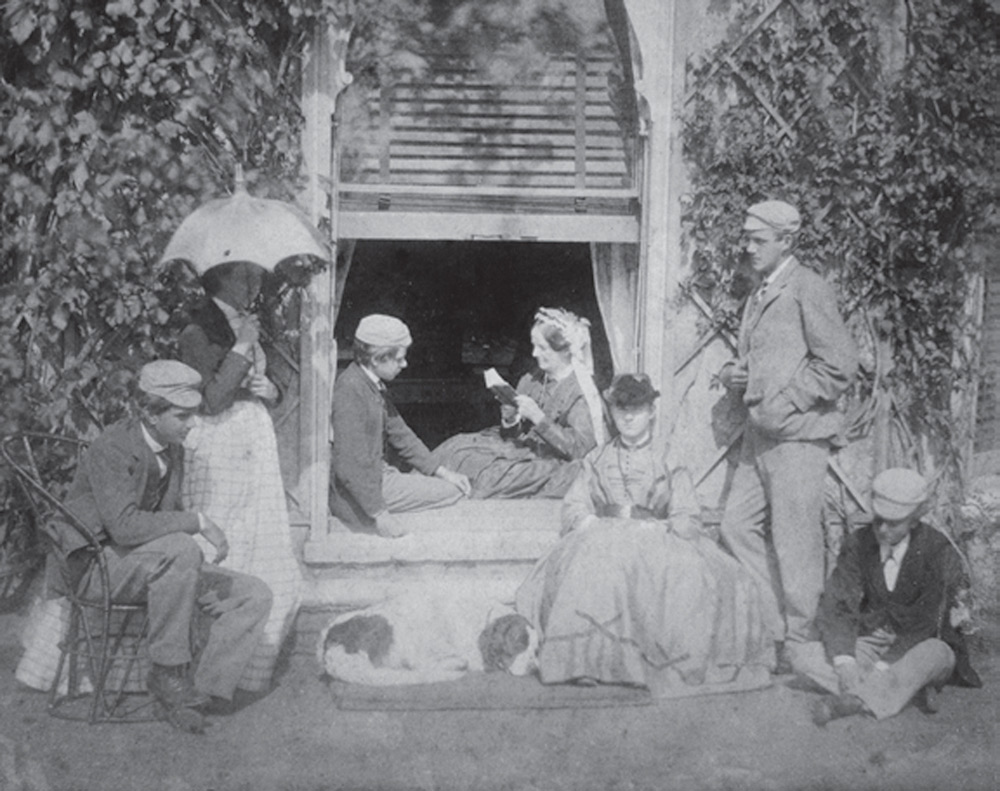

It is a summers day in the early 1860s. The family of Charles Darwin, the notable naturalist and author of The Origin of Species, pose for a photo with their pet dog. The photo is framed around a window facing onto the lawn at their home in Down, Kent. Mrs Emma Darwin, mother of a splendid brood of almost grown-up children, sits in the window frame, wearing a bonnet and reading a book. On the far left of the image sits Leonard, a tall teenager of about thirteen in a jaunty cap. Next is Henrietta, the daughter who assisted her father with his work, standing underneath a parasol. On the windowsill with his mother is Horace, who was only twelve or so; he would later found a world-famous company making scientific instruments. Sitting in wide skirts and a funny awkward little hat that hints at the trickiness of her character is Elizabeth, known as Bessy, who was around sixteen at the time of the photo. And standing to the right of the window is Francis, just a year younger than Bessy, who would share most fully in his fathers scientific work, and inherit most strongly the family passion for dogs.

There is one other person in the photograph: seated on the ground is an unidentified visitor, given a less prominent place in the photo than the dog. We wont ever know the name of the visitor who came to Kent for one sunny day in around 1863, but we suspect the dog is Bob, a big black and white retriever who was made famous forever when his master described his hothouse face in one of his last books, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872).

A hothouse face is one familiar to every dog owner. Its a disappointed, hurt expression, with ears forward, full of pleading and the last traces of hope. In Bobs case, the disappointment concerned the missed chance of a walk. When Darwin left the house by the lawn door, Bob always believed they were both heading off down the garden for the mornings constitutional. He was excited. But if Darwin was actually going off to work in his little conservatory where he did his plant experiments, Bob was prone to take up a dejected attitude at the turning in the path.

For Darwin, the hothouse face almost made him not want to leave Bob, and to carry on walking. But Darwin didnt accuse the dog of doing anything calculated: It cannot be supposed that he knew that I should understand his expression, and that he could thus soften my heart and make me give up visiting the hothouse. For Darwin, the dog was simply acting on its instinct, trying to change his owners behaviour, to make him leave work and go for the desired walk. Even in a simple interaction between owner and dog, Darwin analysed and noted, fascinated by the animal right in front of him.

Darwin recorded his dogs in his books and letters, though rarely as memorably as in the case of Bob. We have few photos of Darwins dogs, loved as they were, because the Darwin family lived just on the cusp of photography becoming available to all. Darwin always consoled himself that hed gone to the effort of having a glass daguerrotype taken of his daughter Annie, in a special trip to London two years before she died in 1851. Yet a mere decade later, a photographer could pack up their portable equipment and come to the house to record all the family, including Bob.

Though Victorian professional photographers advanced their skills with remarkable rapidity, the average black and white image still took many seconds to form, even outdoors on a bright sunny day. The dog in the photo sits at the familys feet, with his head down as if hes been tied to the floor. Perhaps he was tied: Bob has none of the ghostly white traces around his head indicating that he wriggled while the photographer exposed his plate. He seems to have lain perfectly calmly. But organising the photo must have been at least a little complicated nonetheless; perhaps thats the reason for the half-smiles on the faces of Darwins wife Emma, and daughter Elizabeth.

The taking of a photograph perfectly sums up the huge gap between human being and animal. Dogs live within our households as members of the family. But whilst even quite small children can have the need to sit still for a short time explained to them, a dog must be ordered to stay. A dog cannot be persuaded by a bribe, or reasoned with using logic; only a direct order keeps a dog in place. Neither conversation nor persuasion are ever possible. There is an enormous divide between the human and animal worlds.

If the taking of a simple photo is subject to such a communication gap, youd think that humans and dogs getting along in everyday life would be a complicated and chancy business, full of risks. Dogs are, after all, descended from wild animals who hunted for their survival. Human beings living with animals? The analytic intellectual ape, side-by-side with the unpredictable, inexplicable dog mind? Surely the lack of verbal communication, and the fact of two minds so different in so many ways, would render the relationship at least, well, tricky?

Yet for many, the relationship between human being and dog is the calmest, happiest one in their life. The least demanding, and often the most quietly rewarding. Globally, more than 200 million human beings living on the planet today choose to invite one of these animals into their lives: living with them in their homes, sleeping with them in their bedrooms, sharing with them their own food, leaving them alone with their newborn babies. And Darwin was one of them.

When we think of Charles Darwins work on the animal kingdom, we might think of him handling the tiny bodies of Galapagos finches, or examining the massive shells of those islands native tortoises. We think of exotic animals, like gorillas and other monkeys, in the jungles of Africa or Papua New Guinea, thousands of miles from England. Yet the animals with which Darwin had the most profound and sustained contact were the ones that lived with him in his home. Throughout his childhood, and for the years of his grown-up life with his own family at Down House, Darwin owned dogs.

His life with dogs began with Shelah, Spark and Czar, the three most-loved dogs of his teenage years. Then at Cambridge University, he hunted with his cousin, William D. Fox, taking along their dogs Sappho, Fan and Dash. Next came another hunting dog, Pincher, and the little dog Nina, both left behind when Darwin set off for his five-year voyage on the HMS