Geisteswissenschaften InternationalTranslation Funding for Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany

A joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Office, and the German Publishers & Booksellers Association.

Designed by James J. Johnson and set in New Aster type by Westchester

Book Group, Danbury, Connecticut.

Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

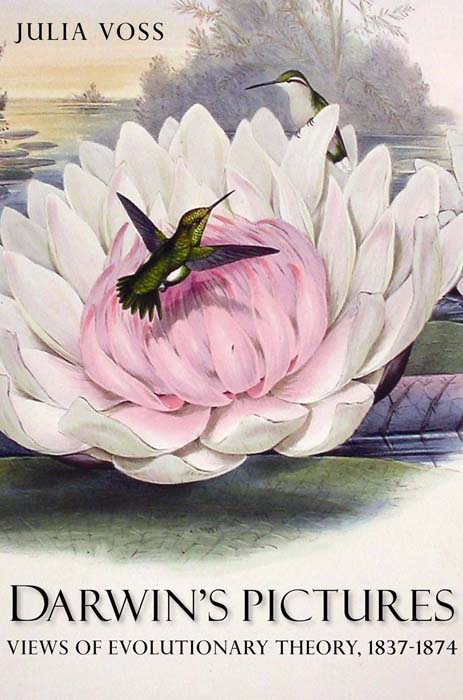

Voss, Julia. 1974

[Darwins Bilder. English]

Darwins pictures: views of evolutionary theory, 18371874 / Julia Voss; translated by Lori Lantz.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-14174-0 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. Evolution (Biology) 2. Darwin, Charles, 18091882. 3. Zoological illustrationHistory. I. Title.

QH366.2.V67413 2010

576.8dc22

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would not exist without the support of many people and institutions. I would like to thank Hans-Jrg Rheinberger as well as my colleagues at the Max Planck Insitute, especially Peter Geimer, Michael Hagner, Anke te Heesen, Bernhard Kleeberg, Wolfgang Lefvre, Staffan Mller-Wille, Henning Schmidgen, Skuli Sigurdsson, and Margarete Vhringer.

I am very grateful to Nick Hopwood for reading the manuscript and for his valuable suggestions, and to Philipp Osten and Cara Schweitzer, who also read the manuscript.

I also owe thanks to Frank Steinheimer for his help related to the ornithological collection of the British Museum and the Natural History Museum in Berlin and for the discussions about the history of ornithology, which never failed to widen my horizons.

I also owe a debt of gratitude to the staff of the Cambridge University Library and the Darwin Correspondence project, especially Paul White, who gave me much advice and constructive criticism.

Thank you to Tori Reeve for her assistance at the Down House archive.

The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, the Volkswagen Foundation, and the Akademie Schloss Solitude all provided valuable financial or institutional assistance.

In addition, Jochen Bttner, Alexander Damianisch, Max Mller-Hrlin, and Kostas Murkudis provided highly appreciated support, corrections, advice, and more.

I thank Barbara Liepert of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Sunday edition for sending me around the world in the tracks of Darwin and Wallace.

I thank my two anonymous referees for their helpful and supportive criticism. My sincere thanks go to Jean Black, Joseph Calamia, and Jeffrey Schier of Yale University Press for making this book possible and for parenting the project in such an enjoyable way. I thank the Brsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels for subsiding the translation. Finally, I cordially thank Lori Lantz for her elegant translation.

And last, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my parents.

INTRODUCTION

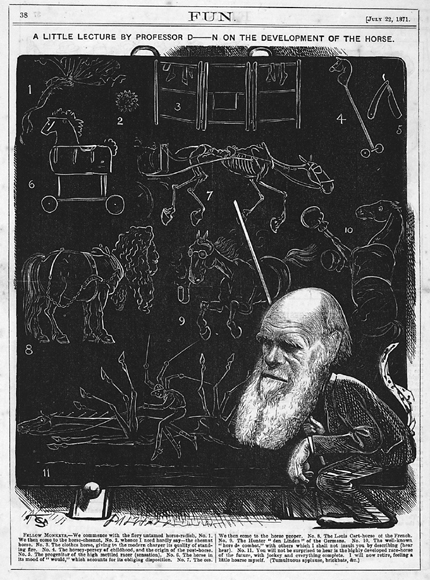

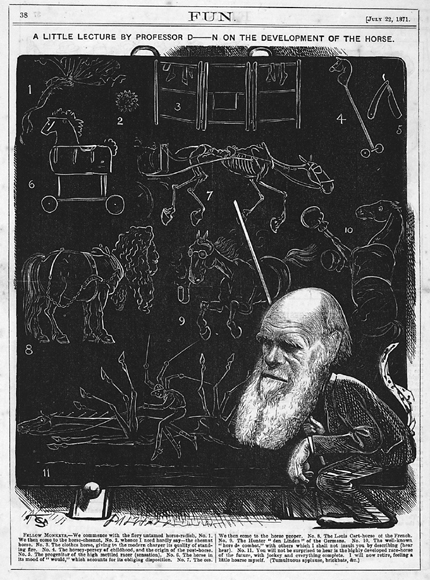

I N July 1871 the English satirical magazine Fun published a caricature of the theory of evolution and its creator (

The picture from Fun combines two elements. The first is Charles Darwin himself, squatting and with a handkerchief fluttering from his pants pocket like an animals tailan image playing on the idea of mankinds kinship with the apes. The other component is the series of drawings mounted on a blackboard, at which Darwin gestures with a pointer. The eleven numbered drawings illustrate a little lecture by Professor D-N on the development of the horse. Number 1 opens the series with a picture of horseradish, while number 11 concludes it with one of an English

Figure 1. Caricature from the July 22, 1871, issue of Fun magazine (Darwin Archive [DAR 255.183], with the permission of the Cambridge University Library Syndicate)

As a historical document parodying actual events, the caricature falls short. From the thorough work of Darwins biographers we know, for example, that he never gave a single public lecture. Publicity-shy and plagued by chronic stomach problems, he avoided speaking in public his entire life. Photographs or engravings do exist, however, that show both his ally Thomas Henry Huxley and his opponent Richard Owen standing in lecture halls and pointing at blackboards. Darwin, in turn, never taught at a university or spoke before a large audience. Furthermore, the historical facts do not correspond to the contents of the lecture Darwin is shown presenting; the evolution of horses was not a topic he explored. Instead, it was Huxley and Owen who lectured on the fossil remains of the horse family, whose origins date to the Paleolithic era. Huxley spoke about the horse fossils to an overflowing lecture hall at the Royal Institution in April 1870, claiming that they offered proof of the existence of evolution. Owen, in turn, had already published on the topic in the 1840s, asserting that the phenomenon proved his archetype theory, in which everything in the animal world was based on one of four structural plans.

Yet, despite these errors, the caricature draws our attention to an important characteristic of evolutionary theory: the high level of visibility it enjoyed during the nineteenth century. Darwin as well as his theory were familiar enough to be parodied in a popular picture, a situation which is quite unusual in the history of science. Very few scientists or scientific images enjoy the prominence granted to politicians, actors, or famous works of artall more common subjects of caricature. But scholarly literature has shown how closely Darwin is identified with his work, as the catchword Darwinism suggests. The worldview based in evolutionary teachings could just as easily have been called Wallacism after Alfred Russel Wallace, who formulated And Darwins theories, as we will see, are closely linked with particular modes of visual representation.

When this book was originally published in Germany three years ago, little was known of the visual history of evolutionary theory. In a pioneering effort, art historian Phillip Prodger had explored Darwins photographic archive and the scientists close collaboration with photographers as he studied the expression of the emotions in man and animals.

Exhibitions marking the 150th anniversary of the publication of Origin of Species in 2009 further expanded our awareness of the visual culture that surrounds evolutionary theory in general and Darwins writings in particular. The Darwin effect, a term coined by American art historian Linda Nochlin to describe the immediate impact of Darwins theory on certain artists, has turned out to be an even broader phenomenon than Nochlin suspected. From the most prominent proponents of impressionism and symbolism to less celebrated but commercially successful and widely known visual artiststhe ramifications of evolutionary thought could be seen everywhere. Exhibitions such as