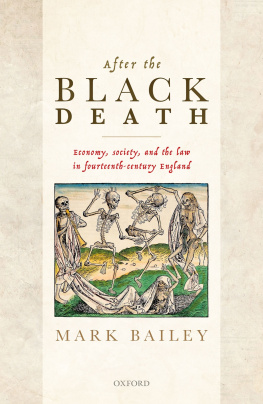

After the Black Death

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Mark Bailey 2021

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2021

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020952083

ISBN 9780198857884

ebook ISBN 9780192599742

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198857884.001.0001

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Preface

In 1991 I wrote an article documenting a dramatic rise in storminess in the North Sea basin between the 1280s and 1340s, which resulted in extensive damage to English coastal communities between the Humber and Sussex (the storminess, not the article) and pointed to an unusual period of sustained, severe, weather conditions. I had neither the courage nor the conviction to draw the obvious conclusion: something significant was happening to the climate, which in turn was driving major economic change. Even if I had, the academic community would have received the argument with polite but deep scepticism. The prevailing intellectual paradigm within economic and social history promoted a binary separation between human agency in long-term change (endogenous factors) and the agency of the environment and microbes (exogenous). Not only were the two regarded as autonomous and independent variables but exogenous factors were deemed to be subordinate to endogenous. Since then, however, global societys preoccupation with climate change, and the advances in our knowledge about past climates gained through scientific research, have comprehensively shifted the paradigm. In 2020 it is now obvious that the storminess in the North Sea was one manifestation of monumental long-term changes in the climate of the Northern hemisphere, which unleashed forces that no human agency on earth could control. Environmental history is now taken very seriously, and climate and human agency are understood to be complex and interdependent variables.

Similar observations hold for our changing interpretation of disease in general, and the Black Death in particular. Nineteenth-century historians were convinced of its primacy in driving social, economic, and cultural change, but views changed during the twentieth century when historians relentlessly downplayed its long-term influence. This downplaying was based in part upon on empirical research into original documents, but it also drew upon a growing societal scepticism about the importance of exogenous factors such as disease. Thirty appalling years of conflict and suffering between 1914 and 1945two world wars, and a global influenza pandemichad generated the highest aggregate level of mortality in the history of humanity, but even these unprecedented catastrophes had not prevented miraculous advances in science and medicine, or subsequent exponential growth in technology and wealth generation. The lesson of the twentieth century seemed to be that neither the human capacity for self-destruction nor the devastation wrought by invisible microbes could trump the creative forces of endogenous change: necessity inexorably stimulated humanity to invent. At the end of the twentieth century, however, two new and terrifying diseases shook this confidence and complacency. AIDS and Ebola reminded society of the capacity of pathogens to jump species and to mutate in ways that can outstrip the medical communitys ability to cope. It cannot be coincidental that, from the 1990s, historians have been much more receptive about the transformative power of epidemic diseases and, as shows, the scholarship on the Black Death changed accordingly.

This preface was written during the UKs lockdown period at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in May 2020. The experience of watching medical science and support structures stretching to breaking point; governments intervening drastically to protect the welfare of their peoples, without necessarily defining exactly what that meant; the introduction of draconian quarantining measures; the emergence of conspiracy theories about the origins of the disease; pointing the finger of blame for its spread; and the appreciation and admiration for frontline carers during the pandemic, all provide partial insights into what coping with the Black Death must have been like in the late 1340s.