Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

THEBLOOD

OF THECOLONY

Wine and the Rise and Fall of French Algeria

OWEN WHITE

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England2021

Copyright 2021 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

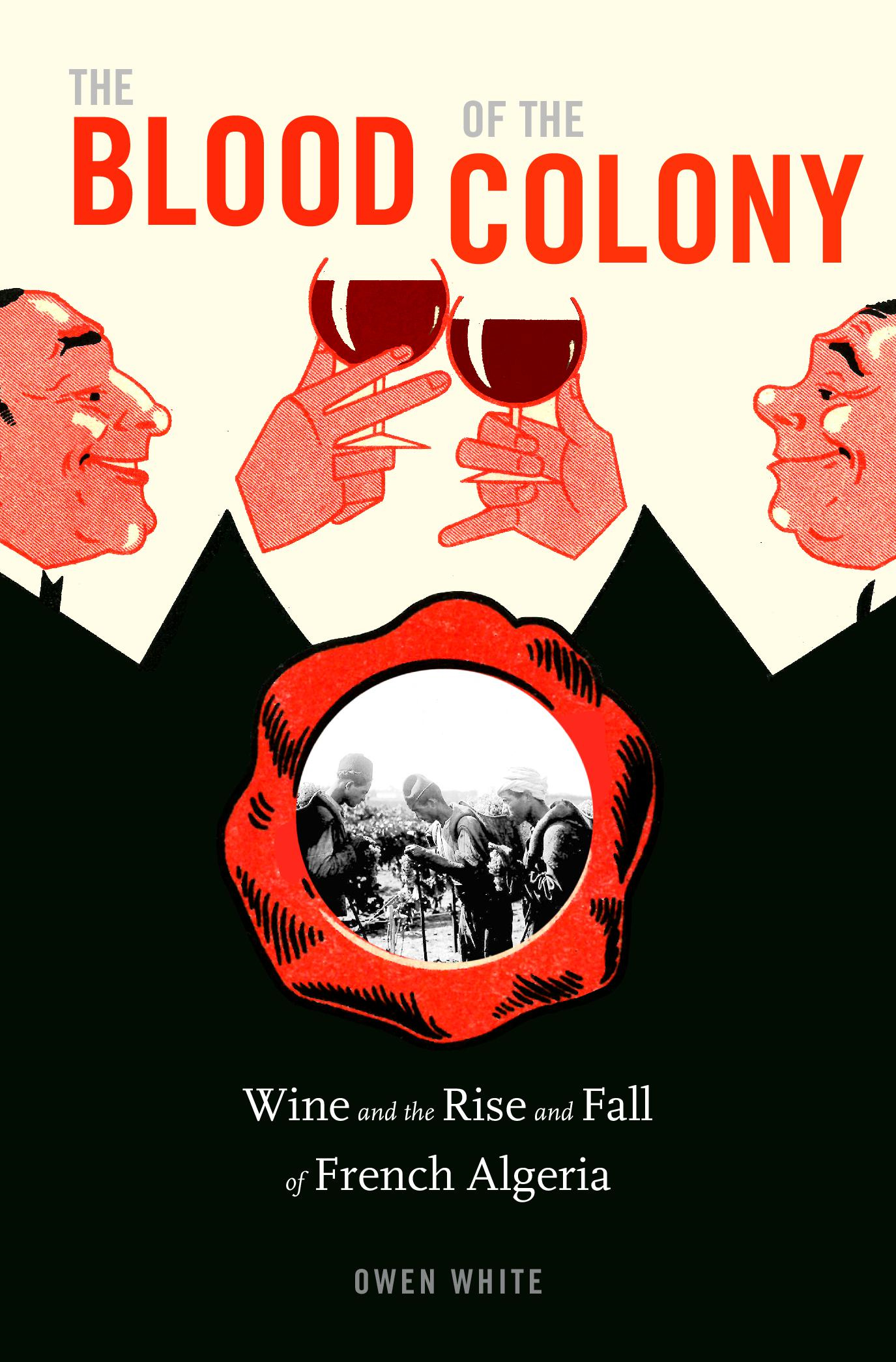

Jacket design: Tim Jones

Jacket artwork: Illustration from an advertisement produced c. 1950 for the Snclauze wine company, Oran, Algeria. Inset: Algerian vineyard workers harvesting grapes near Algiers, 1950s, Centre de Documentation Historique sur lAlgrie, Fonds Madeleine Iba-Zizen, ancienne Directrice de lEcole Normale dInstitutrices dAlger.

978-0-674-24844-1 (cloth)

978-0-674-24945-5 (EPUB)

978-0-674-24946-2 (MOBI)

978-0-674-24947-9 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: White, Owen (Associate professor of History), author.

Title: The blood of the colony : wine and the rise and fall of French Algeria / Owen White.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020017728

Subjects: LCSH: Wine industryAlgeriaHistory. | Wine and wine makingAlgeriaHistory. | DecolonizationAlgeria. | AlgeriaHistory18301962. | AlgeriaPolitics and government18301962. | FranceColoniesAfrica.

Classification: LCC HD9387.A4 W55 2021 | DDC 338.4/766320096509041dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020017728

To Patricia

Contents

Many towns and villages in Algeria changed their names after independence in 1962. Colonial-era names of places mentioned in the text are listed below alongside their postindependence names.

Colonial | Postindependence |

|---|

An-el-Arba | An El Arbaa |

An-Kial | An Kihal |

An-Tdls | An Tdls |

Ameur-el-An | Ahmar El An |

Bellecte | An Boudinar |

Bellevue | Sour |

Birkadem | Birkhadem |

Bne | Annaba |

Bougie | Bjaa |

Cassaigne | Sidi Ali |

Castiglione | Bou Ismal |

Courbet | Zemmouri |

Descartes | Ben Badis |

Djidjelli | Jijel |

Dollfusville | Oued Chorfa |

Dupleix | Damous |

Er-Rahel | Hassi El Ghella |

Fleurus | Hassiane Ettoual |

Fondouk | Khemis El Khechna |

Fontaine-du-Gnie | Hadjret Ennous |

Fort de lEau | Bordj El Kiffan |

Gaston-Doumergue | Oued Berkche |

Jemmapes | Azzaba |

Laferrire | Chaabat El Leham |

Lambse | Tazoult |

Lamoricire | Ouled Mimoun |

LArba | Larba |

Le Gu de Constantine | Djasr Kasentina |

Les Abdellys | Sidi Abdelli |

Lourmel | El Amria |

Maison-Blanche | Dar El Beda |

Maison-Carre | El Harrach |

Marengo | Hadjout |

Margueritte | An Torki |

Mercier-Lacombe | Sfisef |

Mirabeau | Dra Ben Khedda |

Mondovi | Dran |

Montagnac | Remchi |

Mouzaaville | Mouzaa |

Novi | Sidi Ghiles |

Orlansville | El Asnam (changed to Chlef in 1980) |

Palestro | Lakhdaria |

Palissy | Sidi Khaled |

Philippeville | Skikda |

Rio Salado | El Malah |

Rivet | Meftah |

Saint-Denis du Sig | Sig |

Saint-Maur | Tamzoura |

Sidi-Ferruch | Sidi Fredj |

1 kilometer = 0.62 miles

1 hectare = 2.47 acres; 100 hectares = 1 square kilometer = 0.38 square miles

1 hectoliter = 100 liters = 26.4 liquid gallons (US) or 22 imperial gallons (UK)

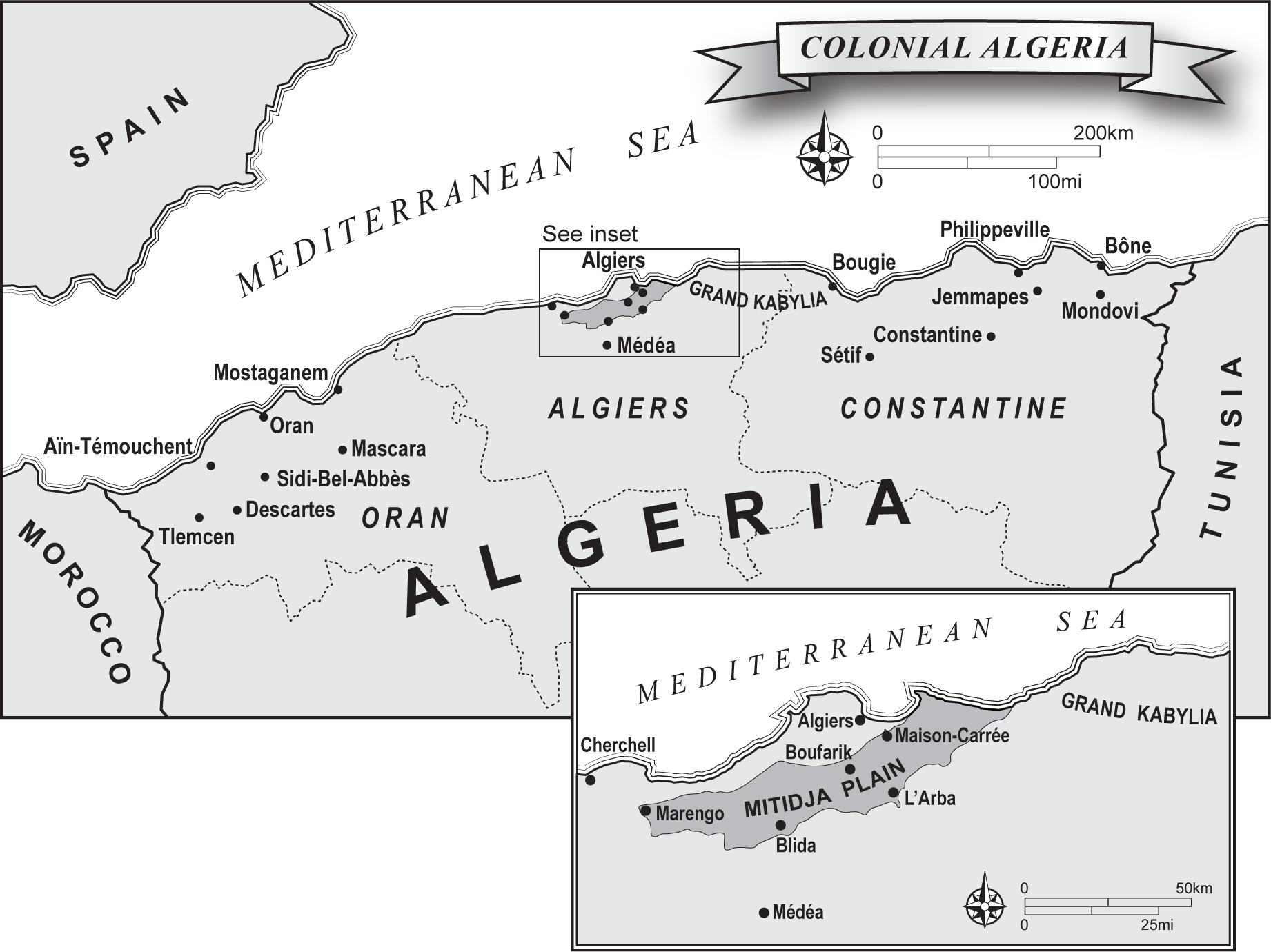

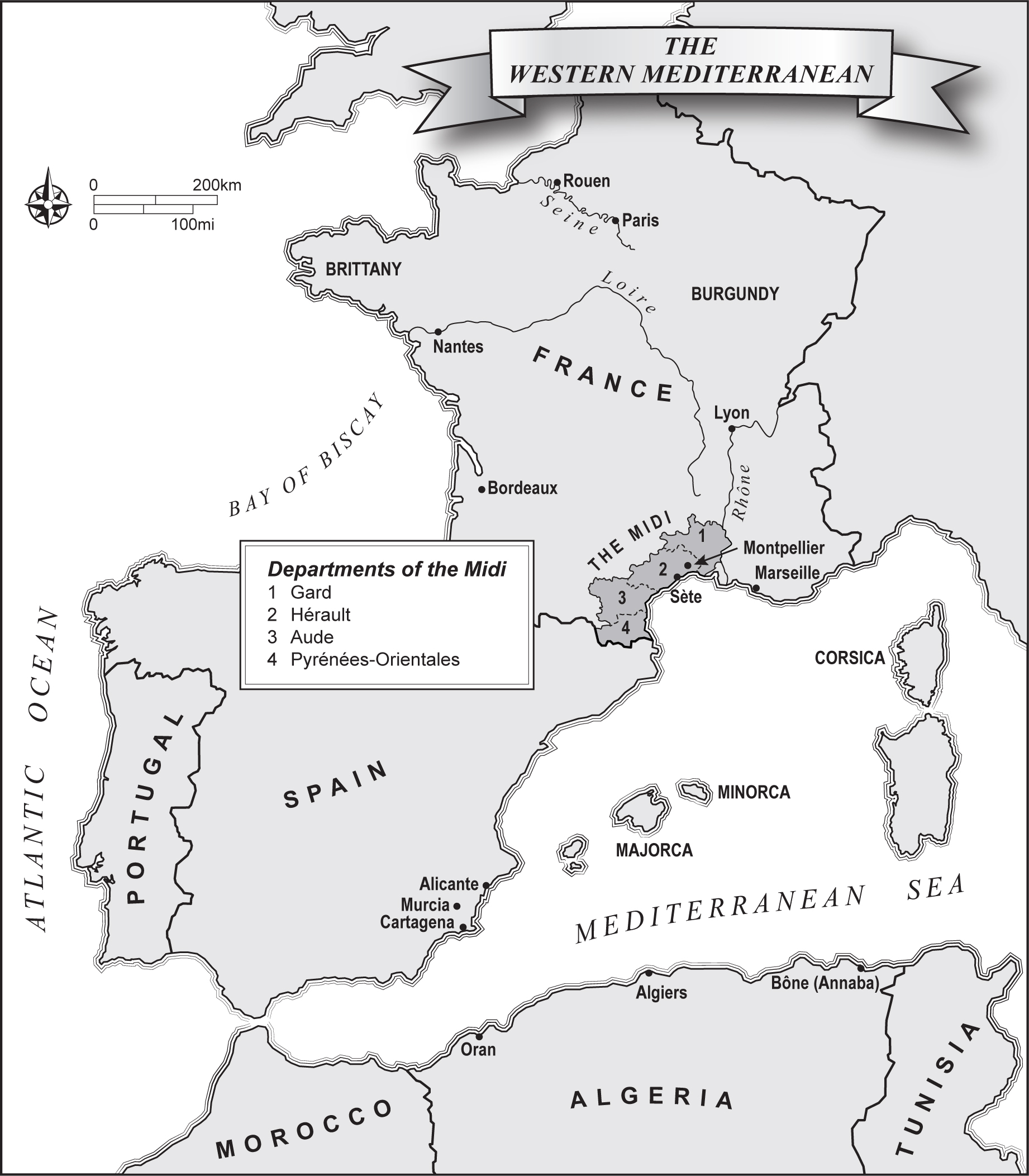

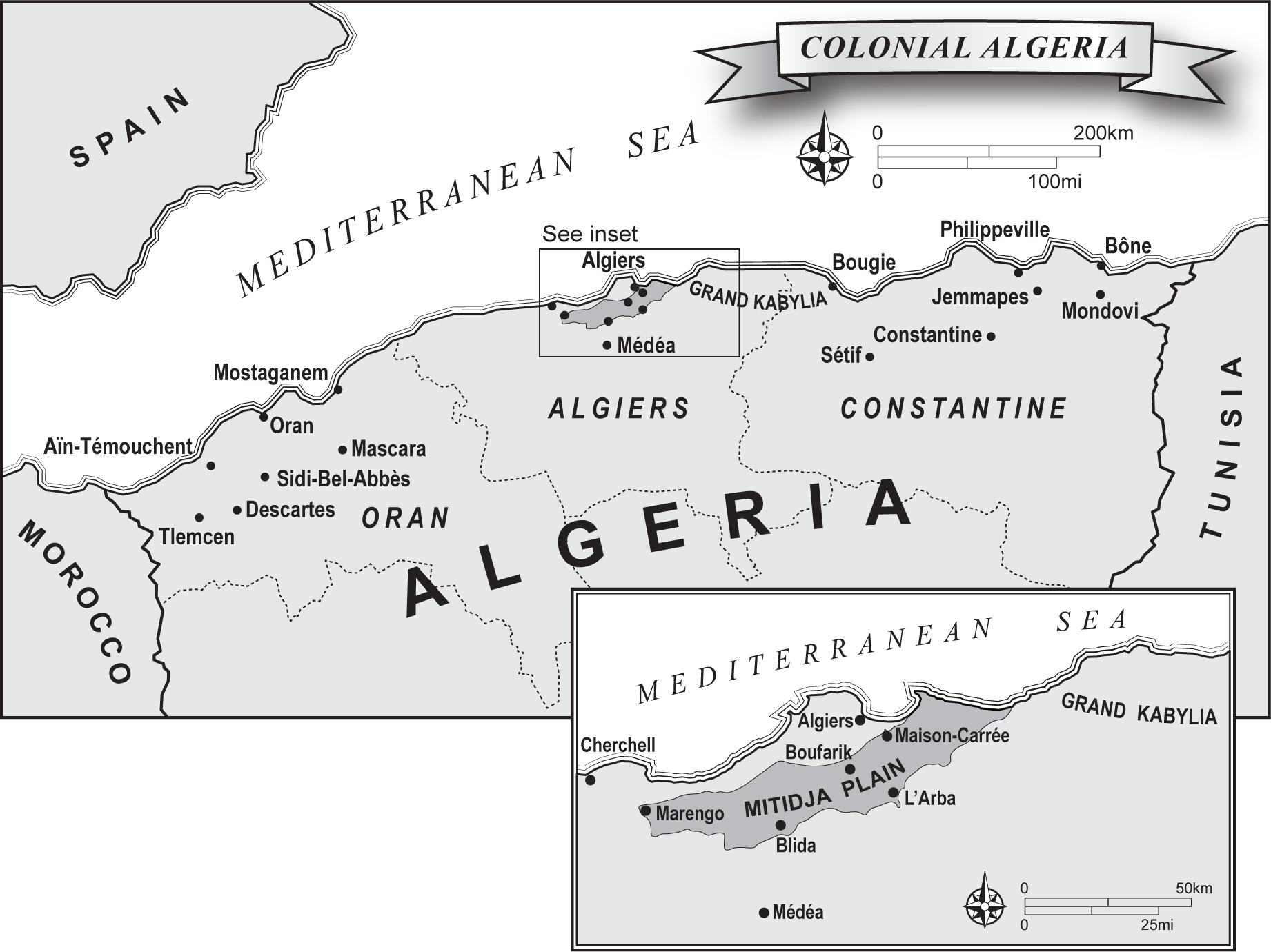

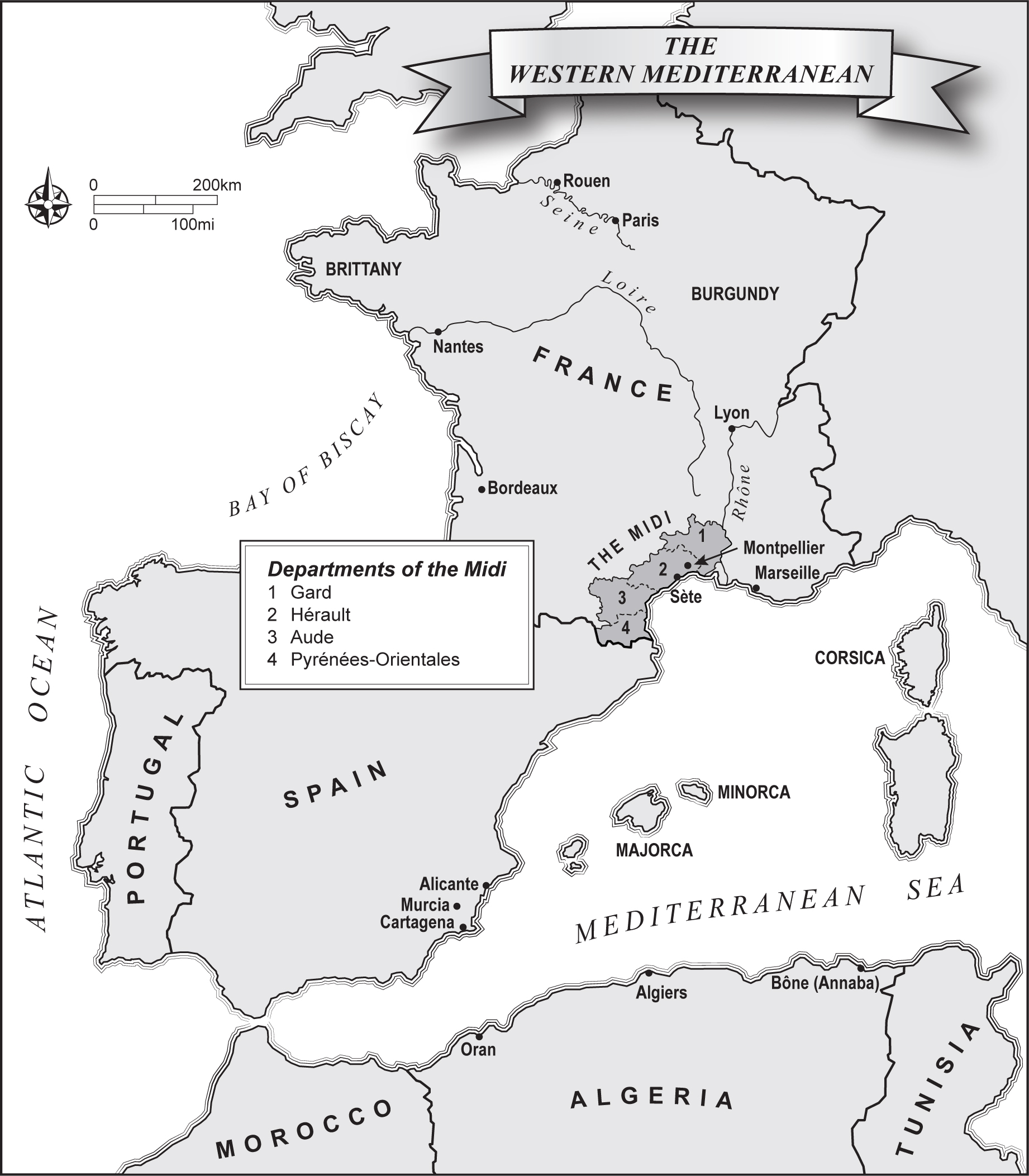

MAP 1Colonial Algeria

MAP 2The Western Mediterranean

For most of the twentieth century, Algeria was the fourth-biggest wine producer in the world. By the 2010s, the three leading producers were the same as in 1900: France, Italy, and Spain. Algeria no longer placed anywhere near the top twenty.

Underlying these basic facts is an extraordinary example of the capacity of modern European imperialists to transform lands in their own image. In the last decades of the nineteenth century, settlers from countries on the European side of the Mediterranean profited from the access to land created by Frances conquest of Algeria to plant tens of thousands of hectares of grapevines. As the rows of vines lengthened, they gave new definition to the imperial edifice known as French Algeria. Wine became the colonys primary export, making fortunes for some while also drawing large numbers of Algerian Muslims into salaried labor. Some of those Algerian workers would eventually help bring French Algeria to a bloody end. Independent Algeria, a Muslim-majority country with a substantial wine industry, then had to decide how far it should undo the transformations the colonists had wrought.

Wine was so central to the economic life of French Algeria, the most important component of the worlds second-largest empire, that it can be used to trace the rise and fall of the colony itself. That is exactly what this book sets out to do.

To study a colonized territory in terms of its rise and fall is to risk embracing a clich of writing about empire. Some historians criticize the rise-and-fall paradigm for reducing complex power dynamics to a simple parabola, as if empires were subject to the law of gravity. As I researched the story of wine in Algeria from the start of the French conquest in 1830 through independence in 1962 and the half-century or so beyond, however, the arc of the production figures came to look very much like a rough measure of the strength of Frances imperial influence.

The chronological structure of the following chapters should make the imperial trajectory clear. Despite the resources deployed in support of military invasion and European settlement in Algeria, the colonys early progress was halting and fragile. But it seemed clear to many that viticulture (the cultivation of grapevines) stood a very good chance of success on the slopes and plains that lay within about sixty kilometers of the Mediterranean. Settlers wide-scale adoption of wine production later in the century placed the colony on a much firmer footing and went along with a doubling of the European population, from about 300,000 in 1870 to 600,000 in 1900. A new wave of vine planting after World War I coincided with what could be seen as the apogee of French Algeria around the time of its centenary in 1930. Though the wine industry maintained its importance thereafter, it faced increasing challenges from rural flight, labor protest, the hardships imposed by World War II, and, ultimately, the nationalist insurrection that catalyzed the end of French Algeria. After independence, wine was the most obvious vestige of the colonial economy until a concerted effort to reduce its prominence (and Frances hold over Algeria) in the 1970s.