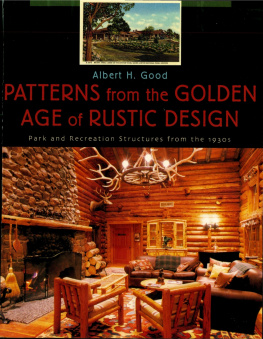

Albert H. Good - Patterns from the Golden Age of Rustic Design

Here you can read online Albert H. Good - Patterns from the Golden Age of Rustic Design full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Roberts Rinehart, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

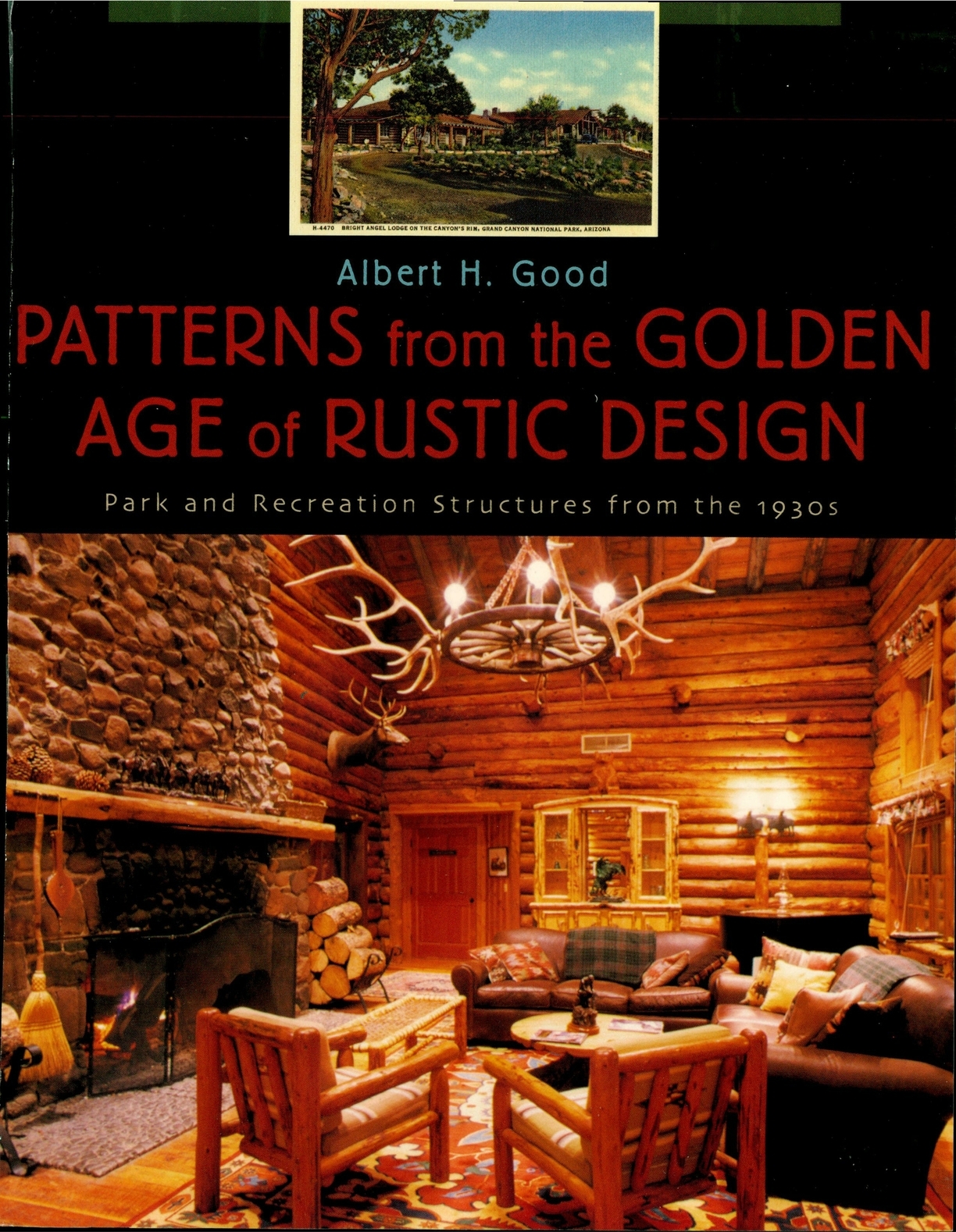

- Book:Patterns from the Golden Age of Rustic Design

- Author:

- Publisher:Roberts Rinehart

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Patterns from the Golden Age of Rustic Design: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Patterns from the Golden Age of Rustic Design" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Patterns from the Golden Age of Rustic Design — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Patterns from the Golden Age of Rustic Design" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

A CHERISHED DICTUM of the many friends of the natural park concept through its formative years has been that structures must be regarded as intrusions in areas set aside to be conserved in their natural state. This unequivocal pronouncement indeed nourished the budding park idea, and has been a favorable and protective influence in its flowering. General acceptance of the principle has so held in check structural desecration of parks that few persons have been moved to brand the statement a half truth, standing very much in need of qualifying amendment to suit todays many-sided park concept. To do so will doubtless be received as a minority report, if not as shameless heresy; nevertheless, the case will be here argued.

A CHERISHED DICTUM of the many friends of the natural park concept through its formative years has been that structures must be regarded as intrusions in areas set aside to be conserved in their natural state. This unequivocal pronouncement indeed nourished the budding park idea, and has been a favorable and protective influence in its flowering. General acceptance of the principle has so held in check structural desecration of parks that few persons have been moved to brand the statement a half truth, standing very much in need of qualifying amendment to suit todays many-sided park concept. To do so will doubtless be received as a minority report, if not as shameless heresy; nevertheless, the case will be here argued.

Time was when only areas of superb scenery, outstanding scientific interest, or major historical importance held interest for the sponsors of natural parks. There was proper concentration on saving the outstanding natural wonders first, and it was probably along with the acquisition of the first superlative areas that structures in parks came to be frowned on as alien and intrusive. Recall that among the sites early dedicated to the idea were the Valley of Yosemite and the Canyons of the Yellowstone and the Colorado! Quick resentment of invasion of such scenic splendor is altogether understandable. Here man must first have felt that his best-intentioned structural efforts had reached an all-time high for incongruity, that structures, however well designed, do not contribute to the beauty, but only to the use, of a park of conspicuous natural distinction. When he concluded that only the most persistent demands for a facility should trap him into playing the jester, he established a principle that remains paramount today for such areasto build only structures which are undeniably essential, and to know he is not equipped to embellish, but only to mar, Natures better canvases. Now and forever, the degree of his success within such areas will be measurable by the yardstick of his self-restraint.

Outstanding, inspiring, breath-taking superlatives in Nature exist by reason of the fact that some comparatively few acres stand out in sharp contrast with hundreds of thousands of relatively unexciting others. Park areas of transcendent quality are often too remote from population centers to be within reach of any great number of citizens. Broad sections of the land, densely populated, are without scenically superb endowment by Nature.

Sensing these facts, the natural park movement could not long remain preoccupied with top-flight Nature alone. The natural park idea was destined for a truly liberal evolution, influenced by such weighing factors as distribution of population, development of the automobile, increase of leisure time, and tardy realization that important among conservational responsibilities of parks was the human crop.

The fact that superlative Nature was beyond gunshot of concentrations of five or ten million people happily did not result in these populations being denied the recreational and inspirational benefits that subsuperlative Nature can provide. It was wisely reasoned that there is more nourishment in half a loaf in the larder than a full loaf beyond the horizonor no loaf at all. Many park preserves have come into being which cannot boast the highest peak or deepest canyon, bluest lake or tallest tree, but do succeed in delivering, f. o. b. metropolitan centers, hills and valleys to pass for superlative in contrast with tenement walls, and swimming, sun, and shade to seem heaven-sent to youth whose wading pools have been rain-flooded gutters of drab city streets.

Tracts, admittedly limited or even lacking in natural interest, but highly desirable by virtue of location, need, and every other influencing factor, bloom attractively on every side to the benefit of millions. It is inexact to term these, in the accepted denotation of the word, parksthey are reserves for recreation. More often than not their natural background is only that contrast-affording Nature which makes other areas superlative. Does such a background warrant the no dogs allowed attitude toward structures so fully justified where Nature plays the principal role? Does it not rather invite structures to trespass to a fulfilment of recreational potentialities and needs, and to bolster up a commonplace or ravaged Nature? It seems reasonable to assert that in just the degree natural beauty is lacking structures may legitimately seek to bring beauty to purpose.

Those who have been called on to plan the areas where structural trespass is not a justifiable taboo have sought to do so with a certain grace. We realize that the undertaking is legitimatized or not by harmony or the lack of it. We are learning that harmony is more likely to result from a use of native materials. We show signs of doubting the propriety of introducing boulders into settings where Nature failed to provide them, or of incorporating heavy alien timbers into structures in treeless areas. We sometimes even experience a faltering of faith in the precision materials produced by our machines, and so evidence an understanding of relative fitness.

As we have vaguely sensed these things, we incline to a humble respect for the past. We become aware of the unvoiced claims of those long-gone races and earlier generations that tracked the wilderness, plains, or desert before us. In fitting tribute we seek to grace our park structures by adaptation of their traditions and practices as we come to understand them.

Thus we are influenced by the early settlers, English and Dutch, along the Atlantic seaboard; something of Old France lingers along the trail of Pere Marquette and the fur traders. Reaching up from New Orleans, Florida, and Old Mexico, Spanish traditions and customs rightfully flourish. Over the covered wagon routes the ring of the pioneers axe is echoed in the efforts of today. The habits and primitive ingenuity of the American Indian persist and find varied expression over wide areas. Interpreted with intelligence, these influences promise an eventual park and recreation architecture, which, outside certain sacrosanct areas, need not cringe before a blanket indictment for unlawful entry.

CONFRONTED WITH THE PRIVILEGE of presenting representative structures and facilities that have found place in parks, from the truly natural park to the recreational reserve, many decisions have been necessary in determining a proper approach. Should such a compilation attribute to the reader no fundamental knowledge of the subject, and become a park primer treating the subject from the ground up literally and figuratively? Should it seek to embrace in all detail every subject of possible interest to the park-minded, assuming in the reader a consuming appetite for knowledgein bulk? Need it concern itself with formulae, diagrams, rules of thumb and rules of fact? Should it become a repository of material, technical and aesthetic, elementary and advanced, and already available from scattered sources?

It is the conclusion that the call is for none of these but only for a comprehensive presentation of park structures and facilities in which principles held in esteem by park planners, landscape designers, engineers, and architects have been happily joined in adequate provision for mans needs with a minimum sacrifice of the natural values present. By avoiding any tendency to be a primer, an encyclopedia, or a handbook of the subject, it is hoped to focus more directly on the current trend in park buildings. It is believed that by making the subjects herein widely available for comparative study, the influence engendered by each will merge into a forceful composite to the advancement of park technique.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Patterns from the Golden Age of Rustic Design»

Look at similar books to Patterns from the Golden Age of Rustic Design. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Patterns from the Golden Age of Rustic Design and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.