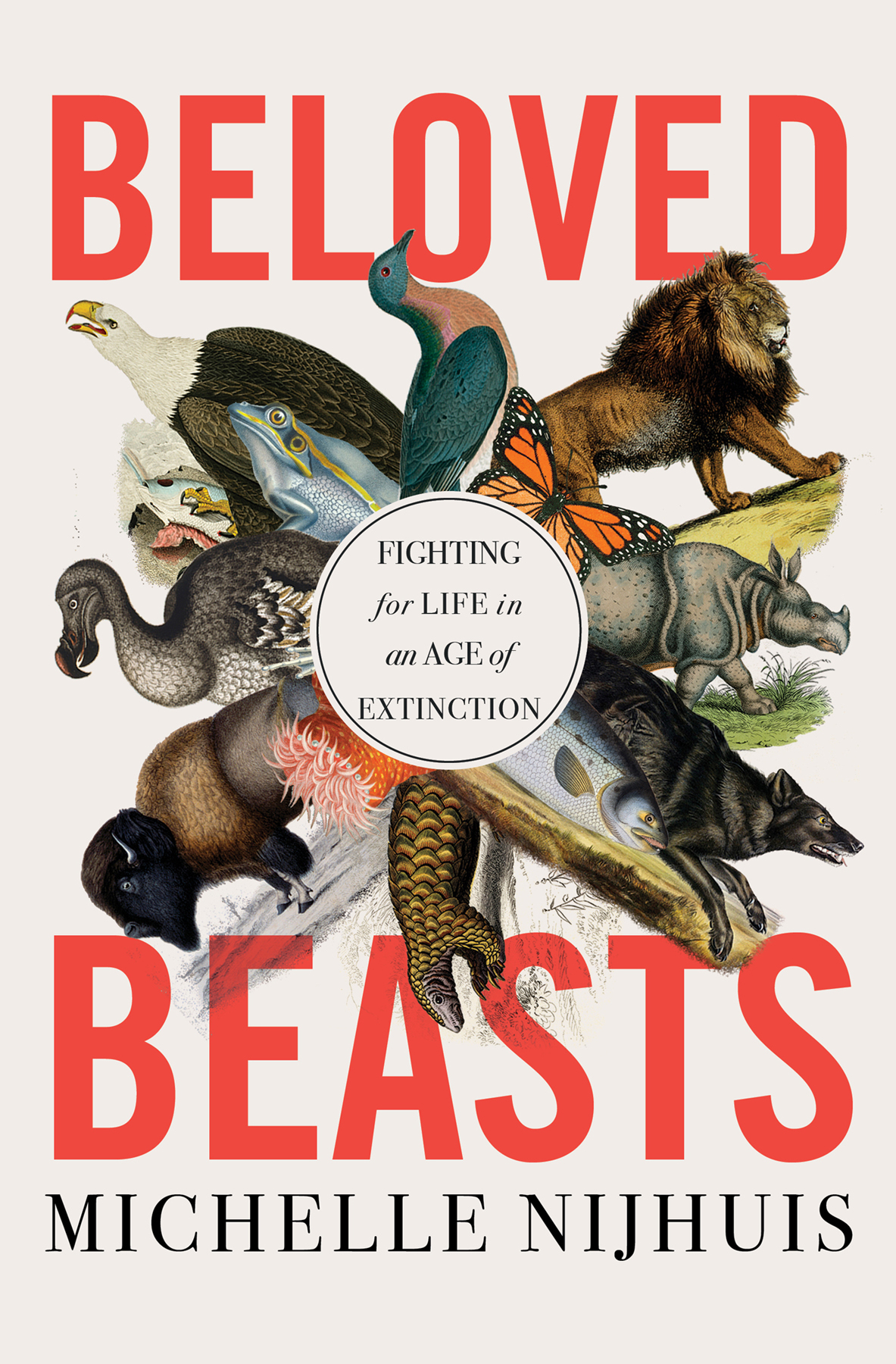

Michelle Nijhuis - Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction

Here you can read online Michelle Nijhuis - Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: W. W. Norton & Co, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction

- Author:

- Publisher:W. W. Norton & Co

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

BELOVED

BEASTS

MICHELLE NIJHUIS

Maybe this is not a song about becoming extinct, though.

Maybe this is a song about becoming.

E. M. LEWIS

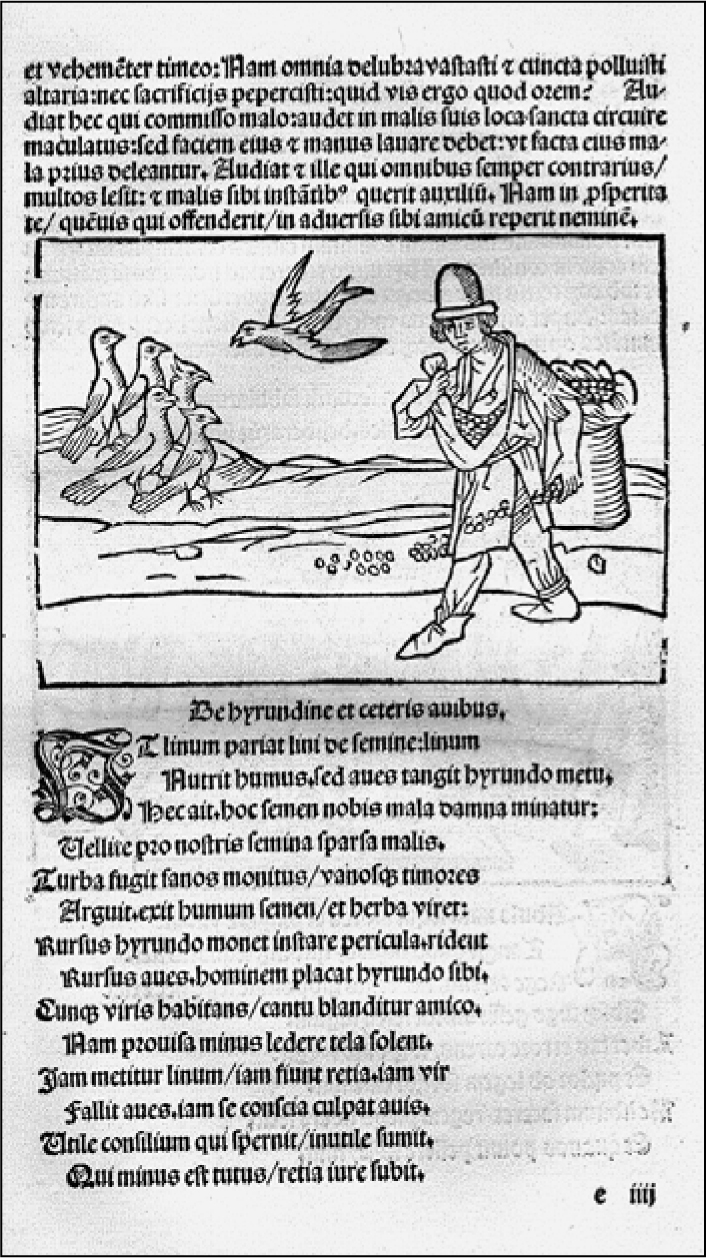

When the swallow first noticed the mistletoe sprouting from the branches of the oaks, she gathered the other birds together, warning that humans would use a paste made from the mistletoe berries to trap them. Unless the birds could manage to tear the plants from the branches, she said, they should band together and beg the humans for mercy and refuge. The other birds laughed at the swallow, so she approached the humans alone. Charmed by her intelligence, the humans gave her sanctuary under their eaves.

Then, they proceeded to kill and eat the other birds.

T his story is one of Aesops fablesor, more precisely, its said to be one of the fables told by an ancient wit called Aesop. Almost nothing is known about Aesop himself, and he may not have existed at all. If he did, he likely lived in the sixth century BCE. He was probably enslaved, possibly imprisoned, and perhaps taken into the confidence of his wealthy captors, his status elevated by his celebrated cleverness. Aristotle, born some two hundred years later, concluded that Aesop was Greek, but others thought he was Anatolian. Some said he was born mute; some said he solved the problems of kings; some said he was the companion of a famous courtesan, in spite of his resemblance to a turnip with teeth. He told odd, unforgettable stories about tortoises and hares, lions and mice, boys and wolves. Legend has it that he talked his way out of trouble many times, until the day his tongue failed to save him and he was thrown off a Delphic cliff, much to the displeasure of the gods.

Generations of tellers have blended Aesops fables with other stories, altering the morals to suit their own time and place. Present-day listeners will never know how his stories sounded when they were first told, or what they were intended to mean. What we do know is that they are rooted in the beginnings of whats often called Western civilization. And while Aesops animal characters are usually proxies for humans, they are animal enough to show us that, even then, humans valued the members of other species in many ways: as individuals and types, calories and bait, companions and omens. Aesops jokes lay in these contrasts, and his jokes were often on us.

What Aesop didnt know, couldnt know, was that more than two thousand years after his death, a few of the inheritors of his fables would recognize a more profound paradox in their own relationships with other species. The swallow, they would realize, was not the only kind of creature in need of sanctuary from themselves.

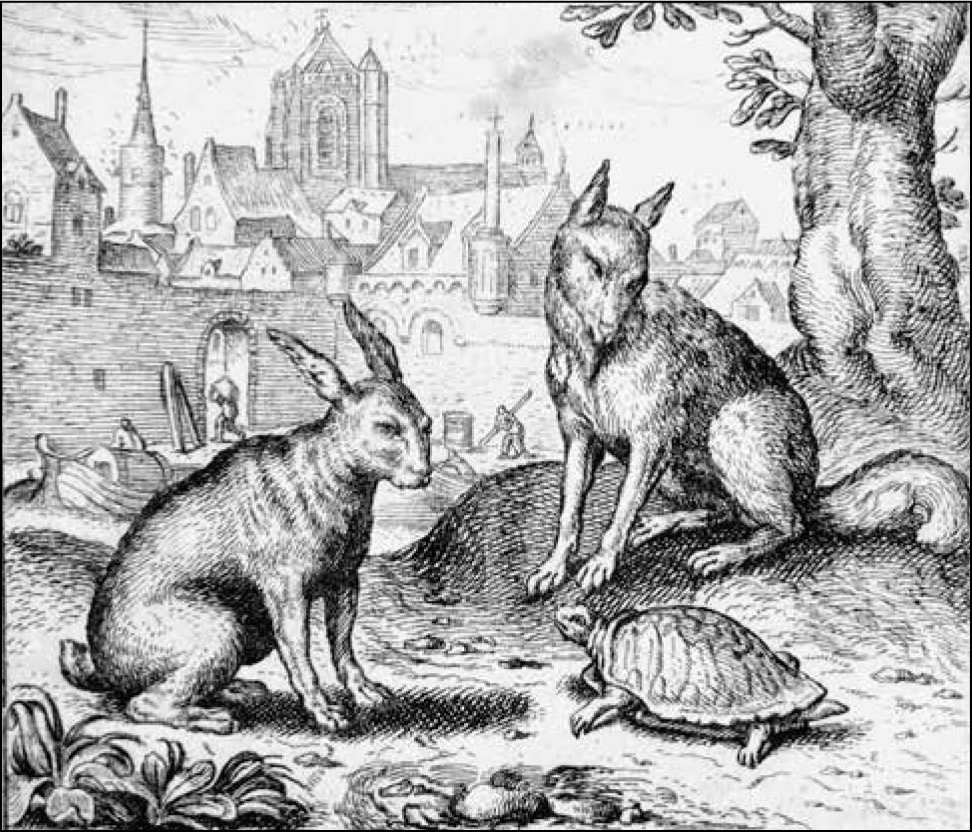

I n the spring of 1994, when I had half an undergraduate degree in biology and precious few practical skills, I was hired as a field assistant on a wildlife research project in the desert of the southwestern United States. My job would have tickled Aesop; every morning before dawn, I hiked alone over the sandstone to a designated spot. There, I waited until the ground warmed and the tortoise Id been assigned to watch dragged herself out of her burrow, blinking with what looked like weary exasperation. I spent the next few hours hovering at a distance, sneaking sips of water as I took notes on when and what the tortoise ate. When the day grew hot and the tortoise finally retreated into the shade, I stumbled back across the burning sand, fighting the feeling that, once again, I had somehow lost the race.

Desert tortoises were, and are, protected as a threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, and my weird, dreamy job was surrounded by bitter and sometimes violent arguments over their future. What struck me was how deep these arguments ran; while people fought over how to give sanctuary to tortoiseswhich construction projects or public-land grazing leases to curtail, which off-road vehicle tracks to closethey were also fighting about why and even whether they should be expected to protect tortoises at all. In the red rock canyons that once sheltered the Ancestral Puebloans, in meeting rooms and courtrooms and small-town coffee shops, people were arguing over nothing less than humanitys proper place on earth.

Woodcut illustrating The Swallow and the Other Birds, 1501.

Engraving illustrating The Tortoise and the Hare, 1609.

After I returned to college and finished my degree, I spent several more years as an itinerant biologist. I searched California streams for endangered frogs and counted wildfire-charred plants in the Sonoran Desert, working with people who poked rattlesnakes for fun and called flowers by their Latin and Greek names. I learned about other species and my own, and later, as a journalist, I started to write about the relationships between them.

For more than twenty years, Ive followed the arguments over the future of other species, and most of them sound familiar: were still fighting over whether and why to provide sanctuary, and still waiting too long to figure out how. This stuckness has a lot to do with money and politics, of course, but it also has a lot to do with historyand with how we see (and dont see) that history today.

After all, it wasnt so long ago that many people in North America and Europe thought they understood their relationships with other animals, and with the groups of organisms called species. The Bible said that God granted humans dominion over the fish of the sea, the fowl of the air, and every living thing that moved upon the earth, and that more or less settled itdespite Aesops rude reminders that the fish and fowl occasionally won.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, these complacent humans learned that they were both less exceptional and more powerful than they had believed. From Charles Darwins theory of evolution, they learned that their ties to other animals were far closer than previously thought. They also came to realize that their rapidly industrializing and globalizing societies could drive species into extinctionand, in fact, had already done so, first on remote ocean islands and then much closer to home.

The most powerful, and powerfully destructive, civilizations on earth are still absorbing this double shock. No matter our creed or culture, most of us would agree that the animals we domesticate for companionship, labor, and sustenance shouldnt be abused (though our definitions of abuse may vary widely). Less clear are our responsibilities toward animals hunted for food and sportand even murkier are those toward animals who are annoying, dangerous, or allegedly useless. The understanding that humans are capable of exterminating entire groups of organisms raised a new question: Why should any of us make sacrifices, even in the short term, to ensure the persistence of other species on the planet?

Until very recently, Western philosophers and religious scholars paid little attention to such questions, and many scientists shied away from them. Laws that try to answer them often raise more dilemmas than they settle.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction»

Look at similar books to Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.