Contents

Guide

Page List

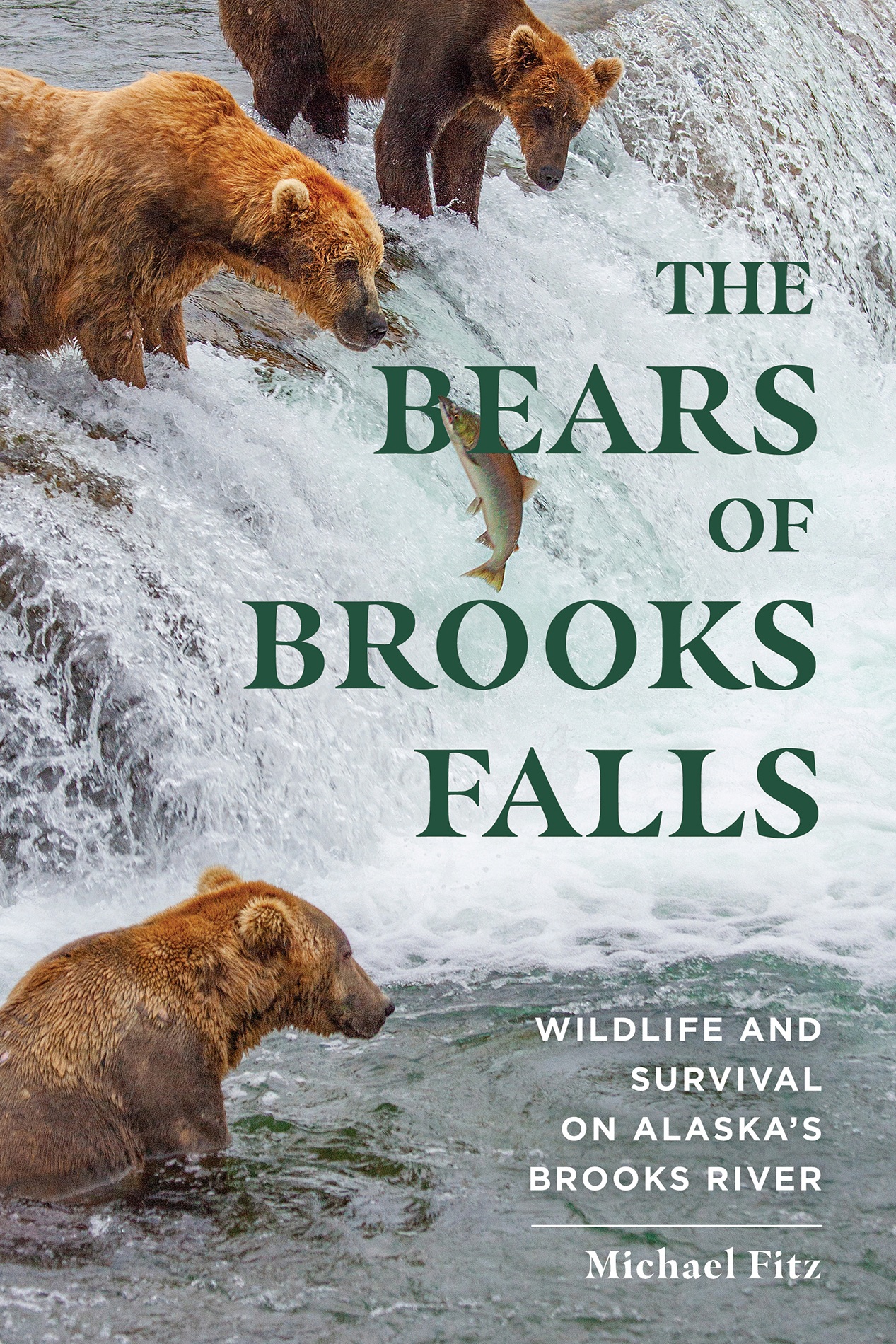

THE BEARS OF BROOKS FALLS

Wildlife and Survival on Alaskas Brooks River

MICHAEL FITZ

CONTENTS

O n the lip of Brooks Falls stands a bear eagerly seeking salmon. Grazer is no rookie here and it shows. She walks to the lip without hesitation and stands firmly against the force of rushing water. She knows exactly where to place her feet and exactly when to lunge, but her skills will be put to the test this year. Shes fishing to fuel more than just her own survival.

Her three young cubs sit warily on the near bank and watch their mother intently. At their vulnerable age, barely two months out of the womb-like den, her success is their success. Mothers milk has been their sole source of calories since they were born in midwinter. Grazer nursed them through spring, using her last precious stores of body fat to fuel their growth and provide them with the strength to embark on the familys migration to the river. Until the salmon arrived, her meals were mostly grassroughage that cant sustain the familys nutritional needs indefinitely.

Several other bears occupy the water below the falls. Two large and very dominant males, known as 747 and 856, bully their way to the most preferred fishing spots. The others jostle for access to any place they can fit in. Enough salmon are here to keep the bears attention, but not enough to allow them to become sated. They wait patiently for their prey to make a mistake.

Instinct compels the salmon to brave the waterfall and return to their spawning grounds. Since hatching three to five years ago, the fish have spent years running a gauntlet of predators, but Brooks Falls presents a new challenge. Theyve encountered nothing quite like it on their journey as near-adults. Now they must overcome the 6-foot-high obstacle or die trying.

Suddenly, a salmon shoots from the water beneath Grazer. She leans toward the fish as it strives to reach the upper lip, but its leap lacks the energy and trajectory necessary to surmount the waterfall and the salmon crashes back into the foam. A moment later, another salmon makes an attempt. Its aim is accurate enough and its momentum is great enough to jump beyond the top of the falls, perhaps its last major obstacle before spawning, if only mom wasnt in the way. With precision, Grazer catches the fish in her jaws and bites down hard. The salmon struggles but not for long. Grazer moves away from the waterfalls edge and devours the whole 5-pound fish in less than a minute. Soon, it will be digested and processed into the fatty milk needed to nurse her growing cubs.

On the Alaska Peninsula,where exceptional landscapes are commonplace, a small river and its namesake waterfall attract attention far beyond its scale. Physically, Brooks River rarely inspires superlatives. Barely a mile and a half long and 50 yards wide, it hasnt carved any deep and torturous canyons. It isnt prone to flood nor does it begin from a tumultuous cascade high in the mountains. Its water is not appropriated for human thirst, agriculture, shipping, or hydropower. Even the rivers single waterfall could be regarded as ordinary in a land filled with active volcanoes, pristine lakes, and a wild, storm-lashed coastline.

Yet, Brooks River is unlike any other place.

Almost 300 miles southwest of Anchorage, Brooks River reigns as the biological and cultural heart of Katmai National Park and Preserve. Katmai is the fourth largest national park in the United States and is larger than any in the contiguous 48 states, yet in the minds of many a small waterfall has become its singular feature. Brooks Falls is no Niagara Falls, Yellowstone Falls, or Yosemite Falls, but what this small waterfall lacks in physical grandeur it exceeds in life. Brooks Falls, and the spectacle that takes place here, is synonymous with wild Alaska.

During my time as National Park Service ranger at Brooks Camp, and later as the resident naturalist with explore.org, Ive never tired of the scene at the waterfallthe fish overcoming tremendous odds to survive and procreate; the bears grabbing salmon out of the air, competing for space, and raising their cubs. Many of the same bears fish at the river day after day, year after year, and I watched them for hours learning who outranked who, how they fished, how they lived. I began to recognize their individuality, seeing, perhaps for the first time, that wild animals werent mindless automatons acting solely on instinct.

Next page