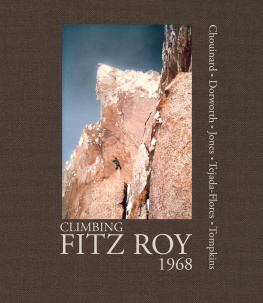

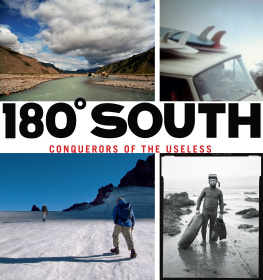

CLIMBING

FITZ ROY

1968

Reflections on the Lost Photos of the Third Ascent

Yvon Chouinard, Dick Dorworth, Chris Jones, Lito Tejada-Flores, and Doug Tompkins

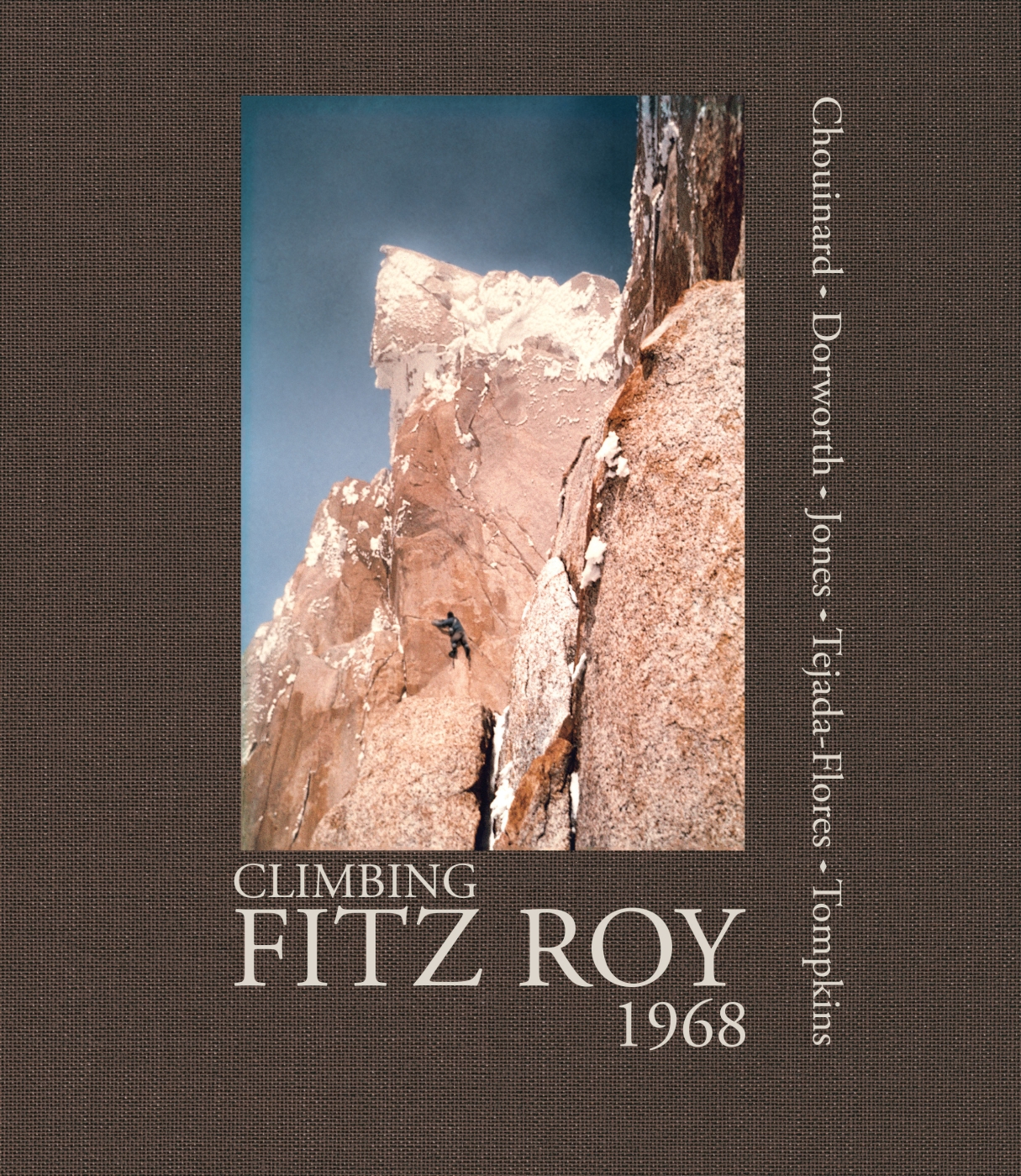

An early view of the Fitz Roy group from the main (dirt) road. Nothing prepared us for this sight of astonishing mountains rising out of dusty and dry plains. - CJ

Foreword

An Extraordinary Power

W hen I met the Funhogs in Lima, Peru, I was amazed that not one of them had a still camera. I had just finished a climb in the Cordillera Huayhuash, where each of my three companions had two Nikon 35 mm SLR cameras and a suite of lenses. While Paul Dix and Roger Hart were photojournalists eking out a living in South America, Dean Caldwell and I had aspirations, at the very least, of showing slides to local climbing clubs back home. These slide shows were part of the climbing ritual, even how you established your bona fides.

My own interest in photography was sparked in my early teens by the incandescent images in Life and Paris Match by photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Alfred Eisenstaedt. At age sixteen, I visited my relatives in the Netherlands and was mesmerized by the Leica 35 mm cameras in a store window. The camera used by my heroes! At that time, post-war Britain had draconian import duties on cameras; we could afford the camera, but the duty would be prohibitive. Still, I bought the one in the window, even though I had to smuggle it through customs. I can still feel the dread as I walked toward the customs agent, with what seemed an enormous and telltale shape in my trouser pocket. My mother, equally nervous, engaged the agent in some chitchat, and somehow we got through.

I loved that Leica IIIC; it was a beautiful object and had a silky smooth action. I spent hours in the murky light of the school darkroom, developing and then enlarging black-and-white film. In 1957, my boys school staged an opera, Circe, written by the music teacher. I cannily talked my way into being the show photographer. Although I sold many dozens of prints, the pictures were rather flat. Of course, schoolboys in Grecian garb and garish makeup were not really attractive in the first place.

Climbing, however, was a more natural subject matter for me. I often toted the Leica along, though not always, for even such a small camera was hard to manage on difficult climbs. Once I moved to California, the work of local masters such as Ansel Adams and Edward Weston inspired me to take a photography class from Jack Welpott. Under his tutelage, San Franciscos decaying industrial buildings and the Big Sur coast became my subjects.

Returning to the Funhog saga, once we reached Santiago, Chile, we began to round up supplies. The list in my notebook said, Film: Ektachrome; Kodak Plus K (a black-and-white film). Then Id written a note: 7 films for $28,about two shots a day for the trip! We used black-and-white film to create prints; color was too expensive. Furthermore, black and white was the medium of serious photographers.

For me the most telling pictures from Peru were of the Andean people. Paul Dix and Roger Hart had made stunning images, the beauty of the people shining through. But curiously, we did not photograph each other in the same way. It seems to me we were too inhibited to poke a lens at our pals, and they in turn were reluctant to poseor in some cases even to sit still or look at the camera. We did not recognize that we were becoming actors on the alpine stage. Where are the insightful climbing portraits from America or even Europe from the 1960s and 1970s? Where was our Annie Leibovitz? I know now what we should have done, but out of trepidation we missed the decisive moment.

Lower down the mountain I sometimes used my Pentax 35 mm SLR with its interchangeable lenses, but on the technical climbs it was too cumbersome. On difficult terrain, I much preferred the far smaller Rollei 35. With an excellent Tessar lens, the Rollei 35 was compact enough to slip into your pocket; it was always at hand and ready to go.

WAS I THE PERSON, THE CLIMBER, THAT I BELIEVED I HAD BEEN? THOSE EVENTS SHAPED WHO I WAS, AND NOW THEY WERE RECEDING INTO THE DISTANCE.

Once home in January 1969, I went through the usual process of removing the Kodak-provided cardboard slide mounts, washing the slides, and then laboriously mounting them between glass with an adhesive edge tape. They were then stored in boxes with slots and a space for captions. But after a small flurry of shows, the slide containers slowly gathered dust over the years. Moved from home to home, they remained undisturbed.

On July 31, 1996, our home was destroyed in a wildfire. With the surrounding roads closed, air tankers dropping fire retardant and firefighters fully engaged, my wife, Sharon, and I reached our home via a dirt track on the back of a neighbors motorbike. To our relief, our wheaten terrier Sadie was wandering around in the parking areathe firefighters had discovered her lying by the door as they entered the house and revived her with oxygen. Henry, our other wheaten, and our cats, Rufous and Zoe, all perished. It was a terrible blow. Negatives, prints, notebooks, slidesmuch of the fabric of my lifewere all gone.

While I had not looked at the artifacts for years, their loss had a strange effect. I began to wonder whether I had really lived through all those experiences. Was I the person, the climber, that I believed I had been? Those events shaped who I was, and now they were receding into the distance. Fortunately, a 1998 phone call from my English climbing companion, Jerry Lovatt, pushed these doubts aside. He asked me to be the keynote speaker at an Alaska symposium to be staged by the Alpine Club in North Wales; I was legitimate after all! When I accepted the invitation, I did not have one slide for such a talk. Former partners helped me out with duplicate slides of my lost photos. But none of the Funhogs I contacted could find their copies. Somehow, those images of an unforgettable climb had drifted away.

Several years later, and quite by chance, Dick Dorworth came up with the missing photos. In a real sense, he returned these events to me, to us. When I think of my life, it is often through the photographs of those times.

I can still remember the prints in photo albums and the framed ones that hung on my walls. Those original pictures are long gone, yet I can still see them in my minds eye, and through those reimagined images, the equally long-gone events come back to life. Photographs, for me, have an extraordinary power.

Chris Jones Glen

Ellen, California

Foreword

Perseverance, Patience, and a Bit of Luck

E arly on the morning of December 20, 1998, I was in the tiny studio apartment I rented in Ketchum, Idaho, drinking coffee and getting ready to go skiing. The phone rang. On the other end of the line was a British accent asking, Where were you on this day thirty years ago?

Caught off guard, my mind drew a blank. I dont know, I replied.

Ahhhhhhh, does the name Fitz Roy ring a bell?

Of course it did, and it all came back into focus. We had climbed Fitz Roy thirty years earlier. Is this Chris?

And of course it was, Chris Jones, the expat Brit who lives in California, the fine climbing historian, friend, and Funhog companion and still photographer on the grand journey to climb Fitz Roy, checking in to commemorate our great adventure together.