tools for grassroots activists

Edited by

Nora Gallagher & Lisa Myers

Cover: A coastal grizzly greets the dawn in Katmai National Park, Alaska.

A howling coyote answers a call from the valley below. Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. Florian Schulz

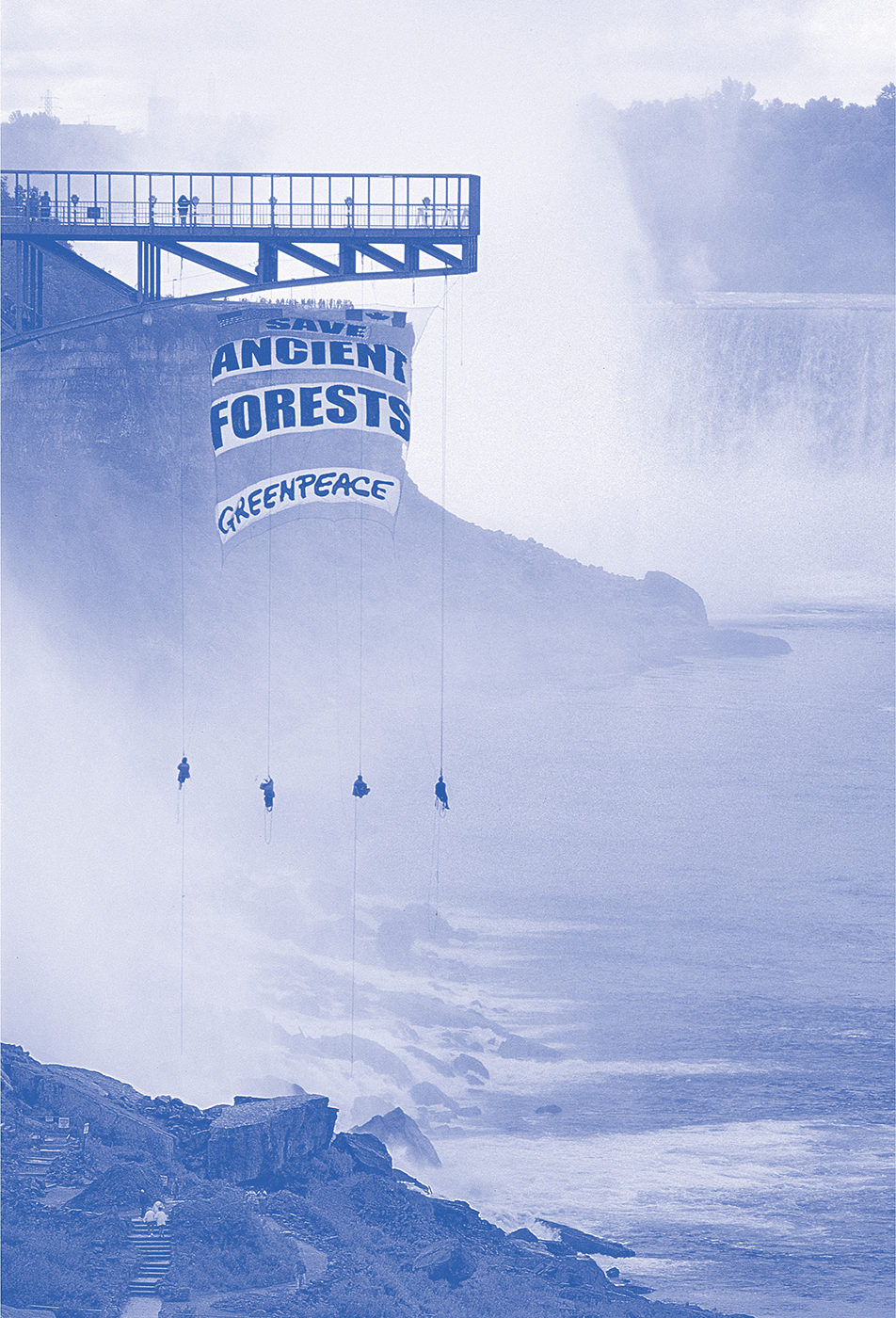

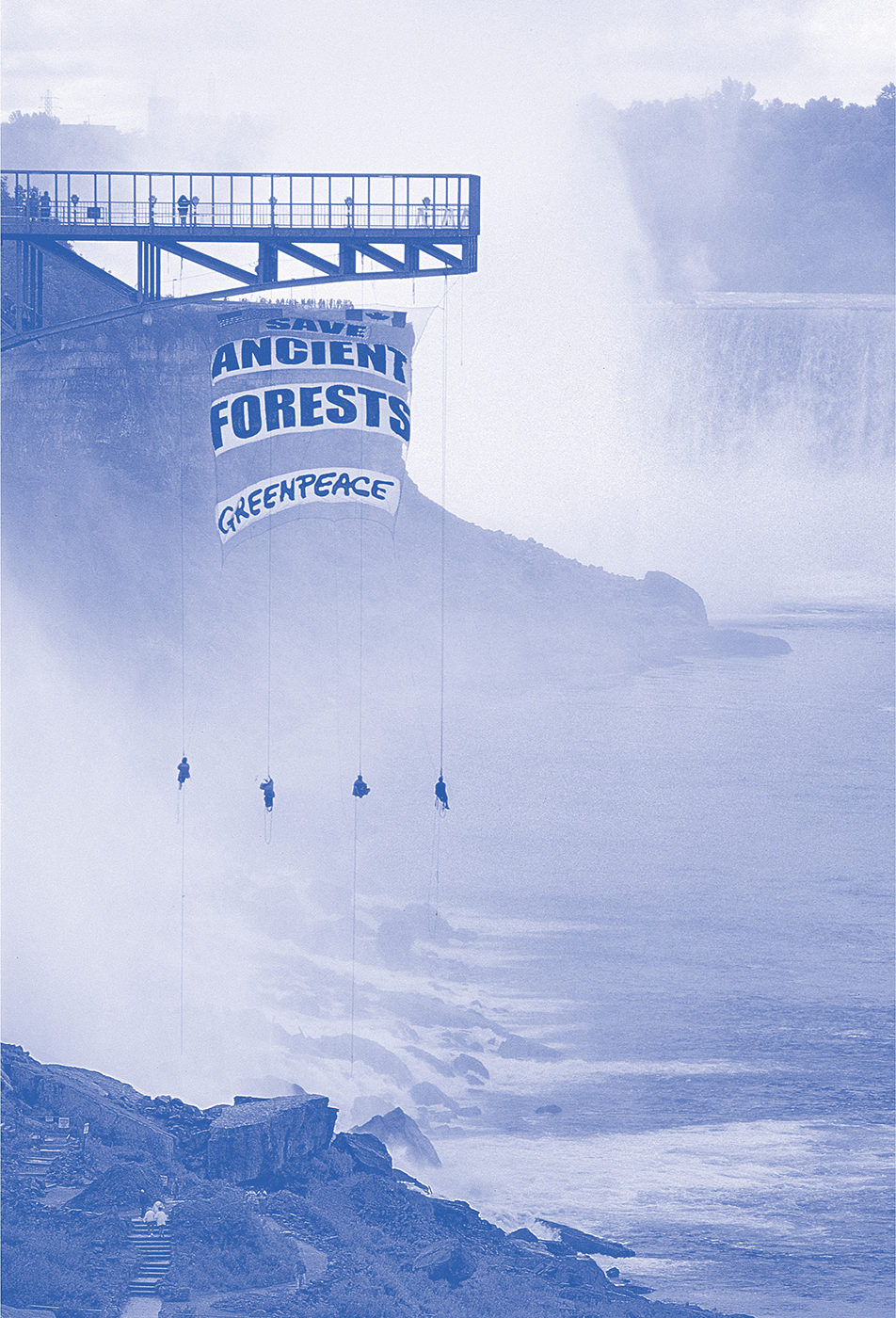

Greenpeace activists hang a banner off the Prospect Point observation tower above Niagara Falls to protest forest destruction, ca. 1998. New York. Joe Traver/Greenpeace

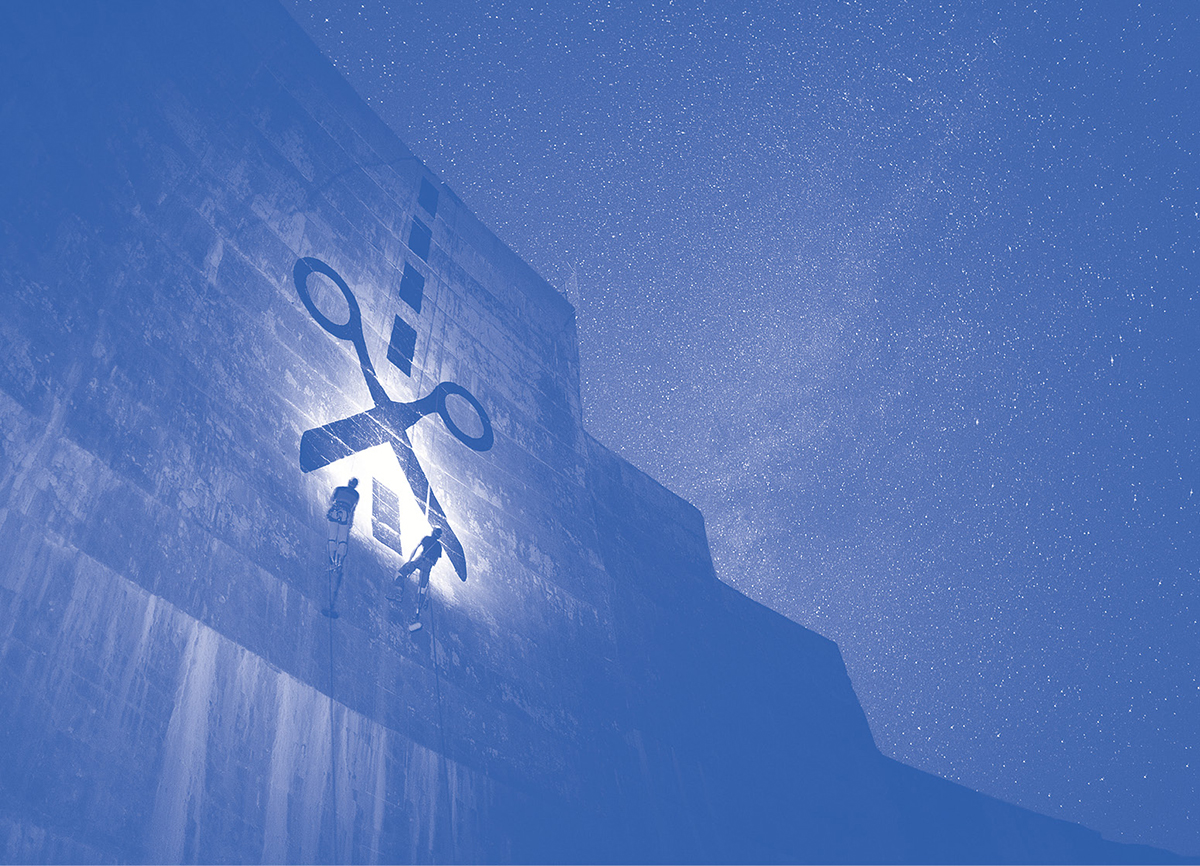

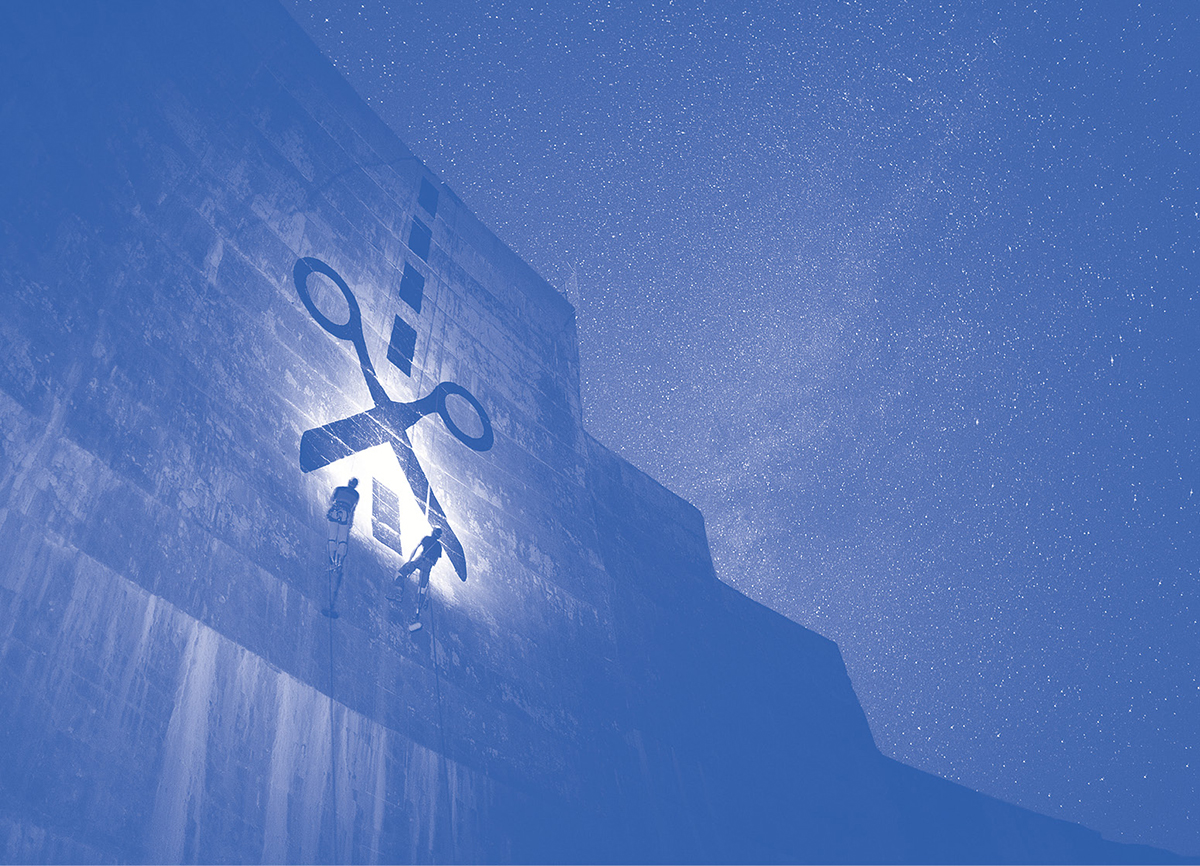

2:30 a.m. on the Matilija Dam, with another 100 feet of dotted line left to paint. California. DamNation Collection

tools for grassroots activists

Best Practices for Success in the Environmental Movement

Edited by

Nora Gallagher &Lisa Myers

Introduction by Yvon Chouinard

Riders in the 2007 Cabalgata Patagonia Sin Represas (Horseback Ride for a Patagonia Without Dams) protest HidroAysn and its plan to put five massive hydroelectric dams on the Ro Baker and Ro Pascua, Chile. Henry Tarmy

The confluence of the Ro Baker and the Ro Nef, Aysn, Chile. Ross Donihue/Marty Schnure

contents

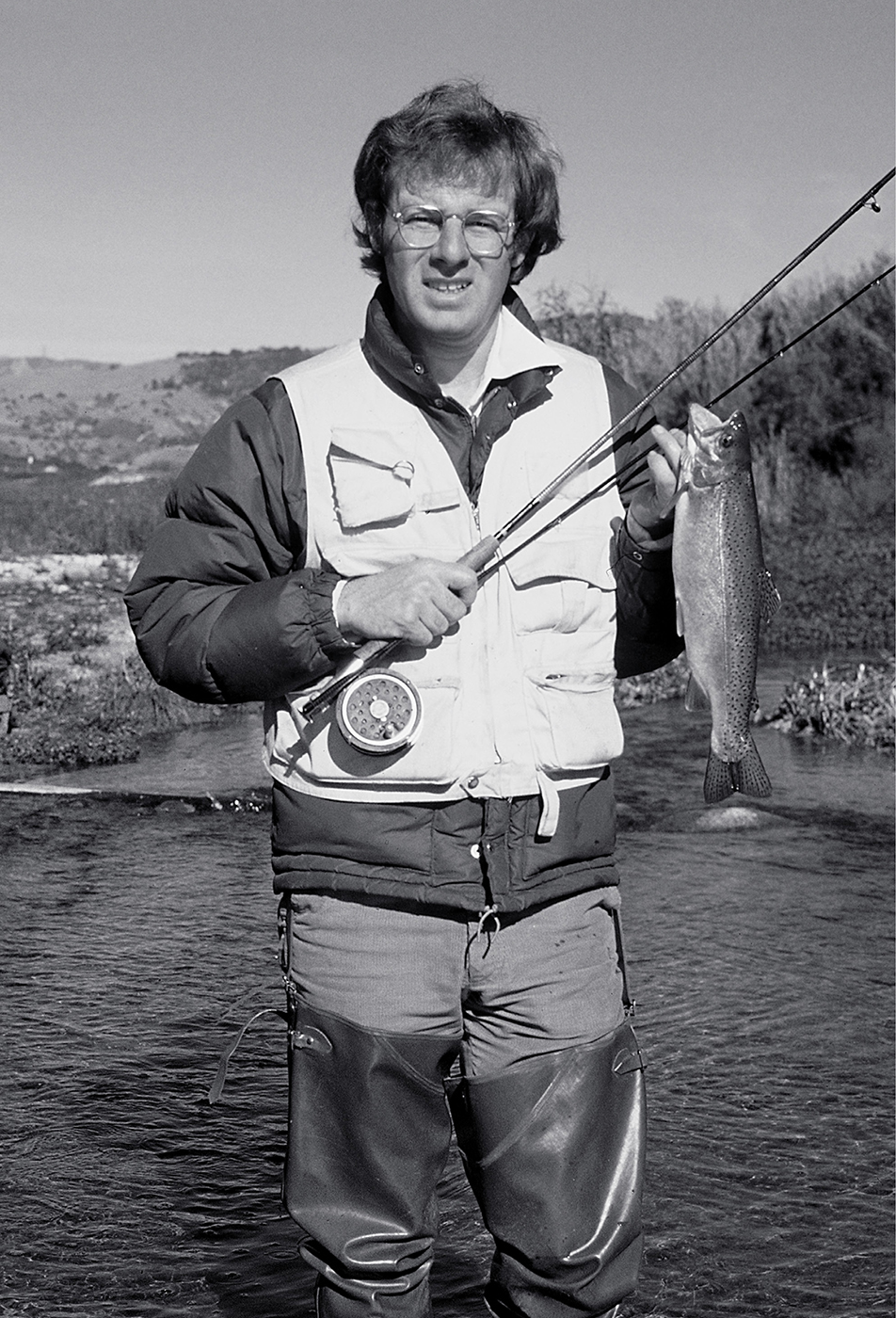

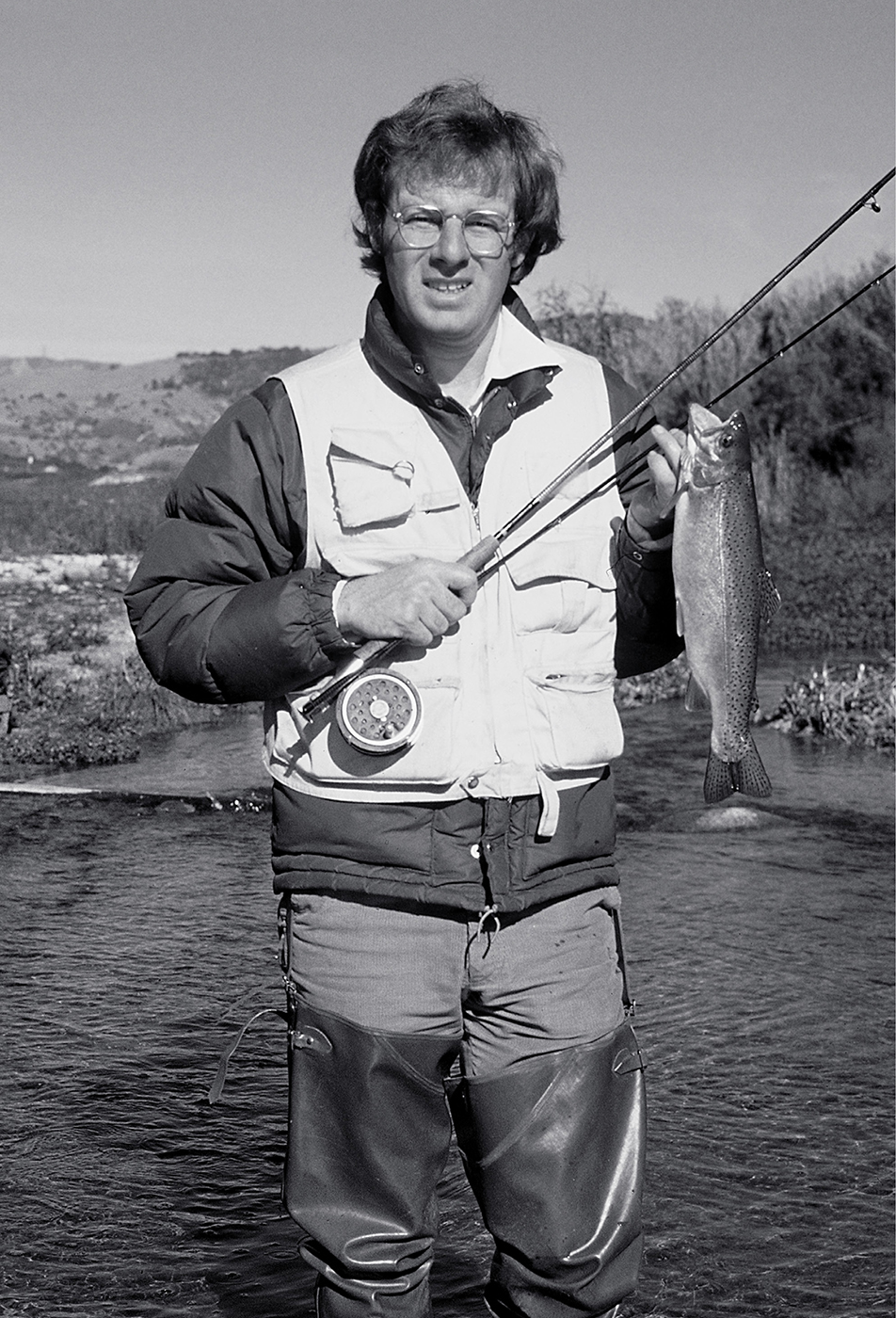

Mark Capelli fishing for southern steelhead in the Ventura River, ca. 1978. Ventura, California. Photo Courtesy of Mark Capelli

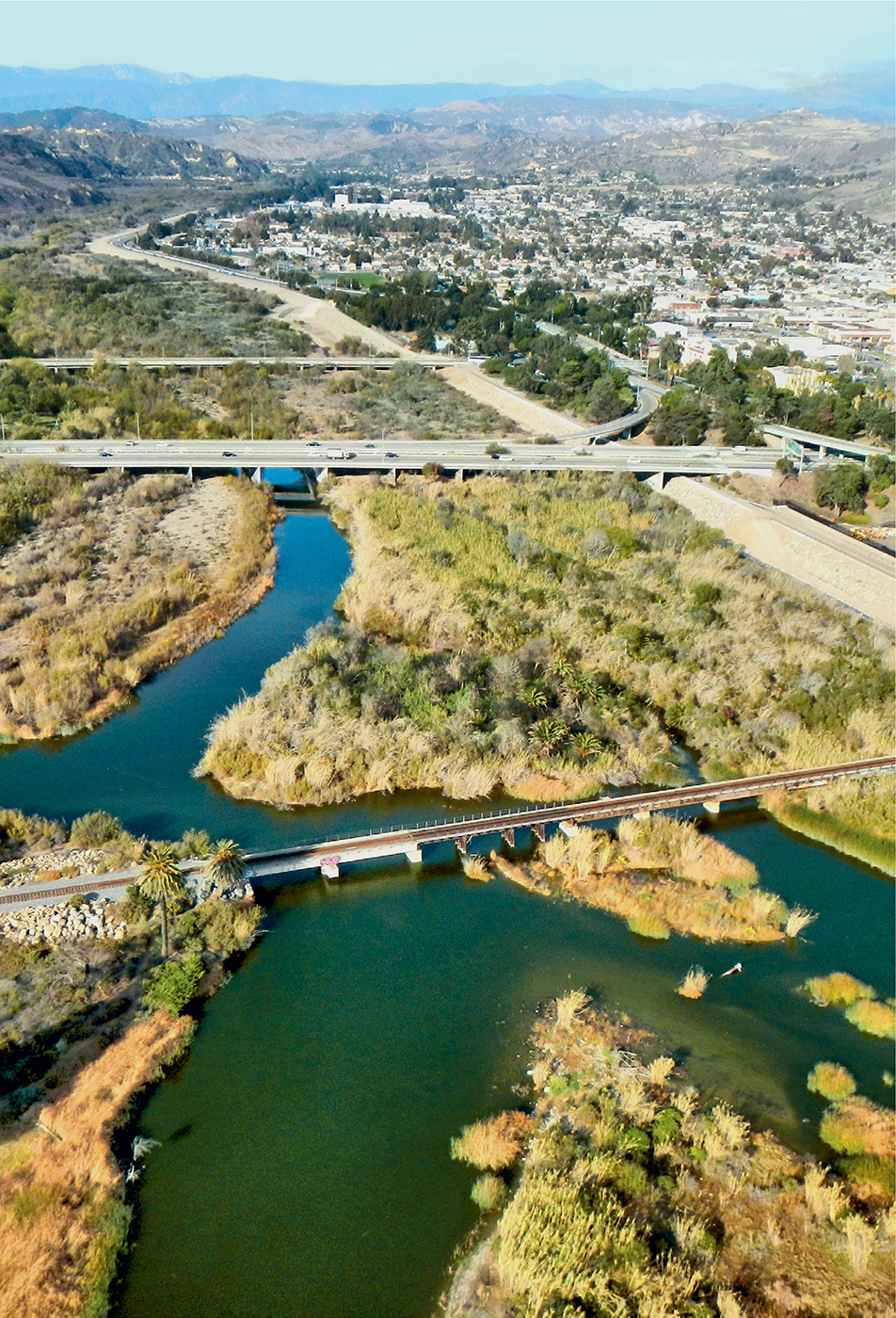

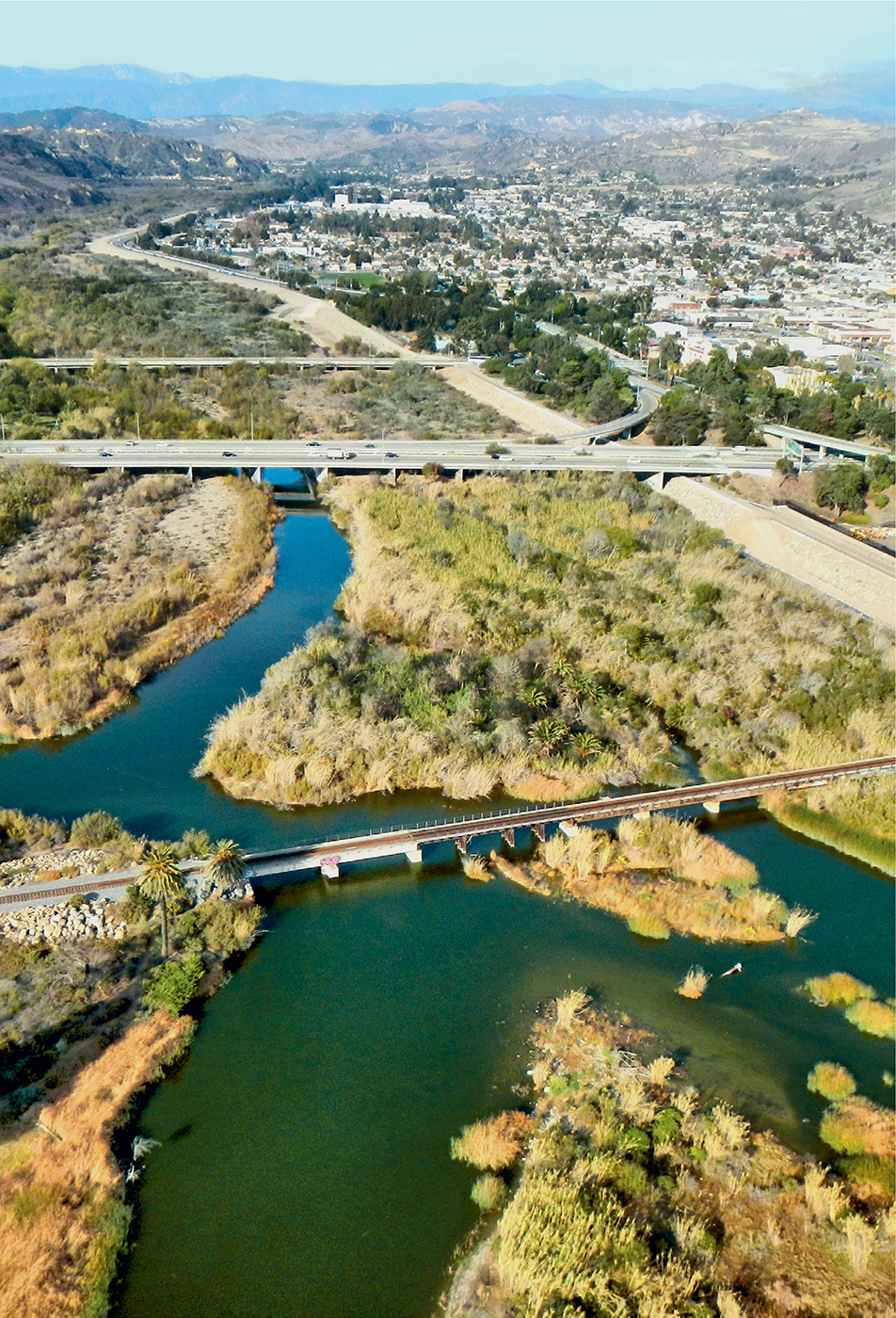

Aerial view of the mouth of the Ventura River in 2014. Ventura, California. Rick Wilborn

Why a Tools Conference?

Yvon Chouinard

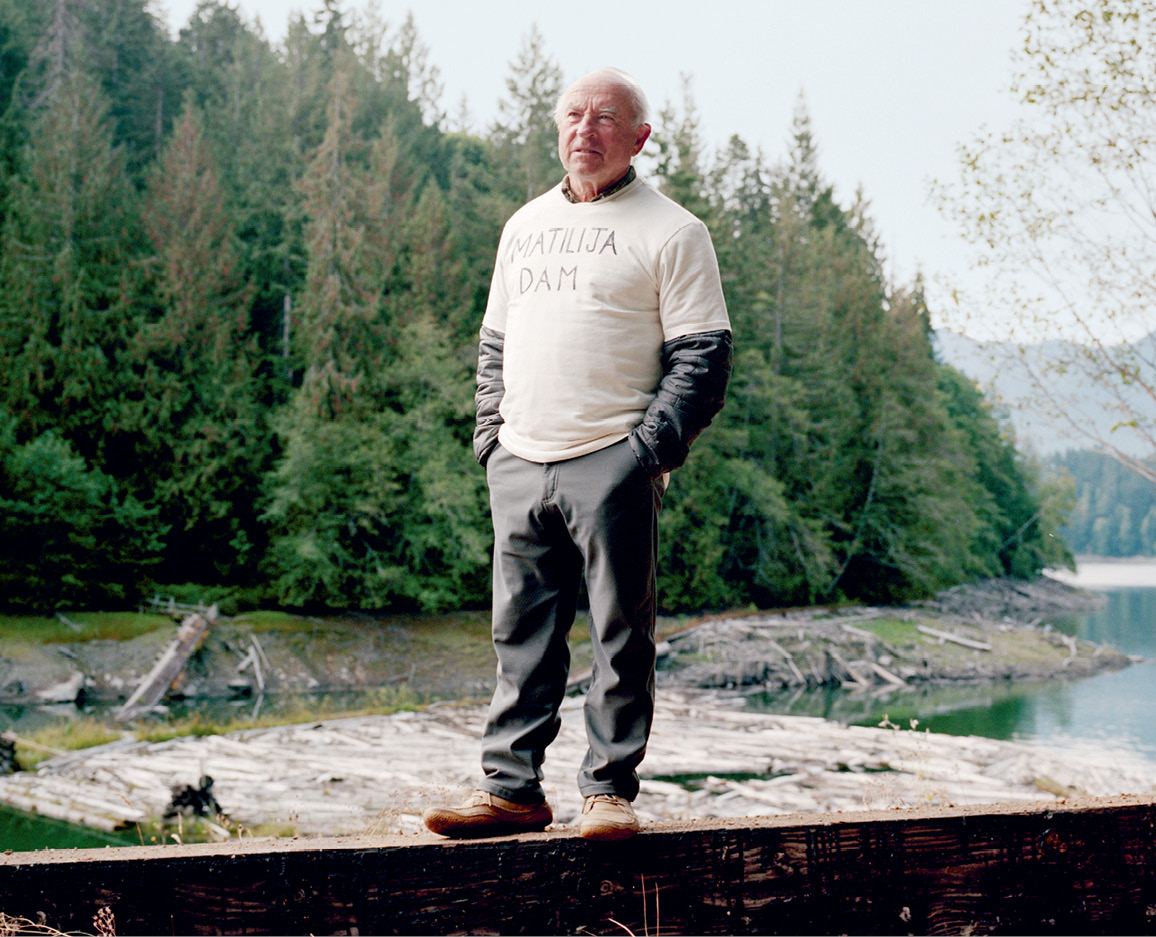

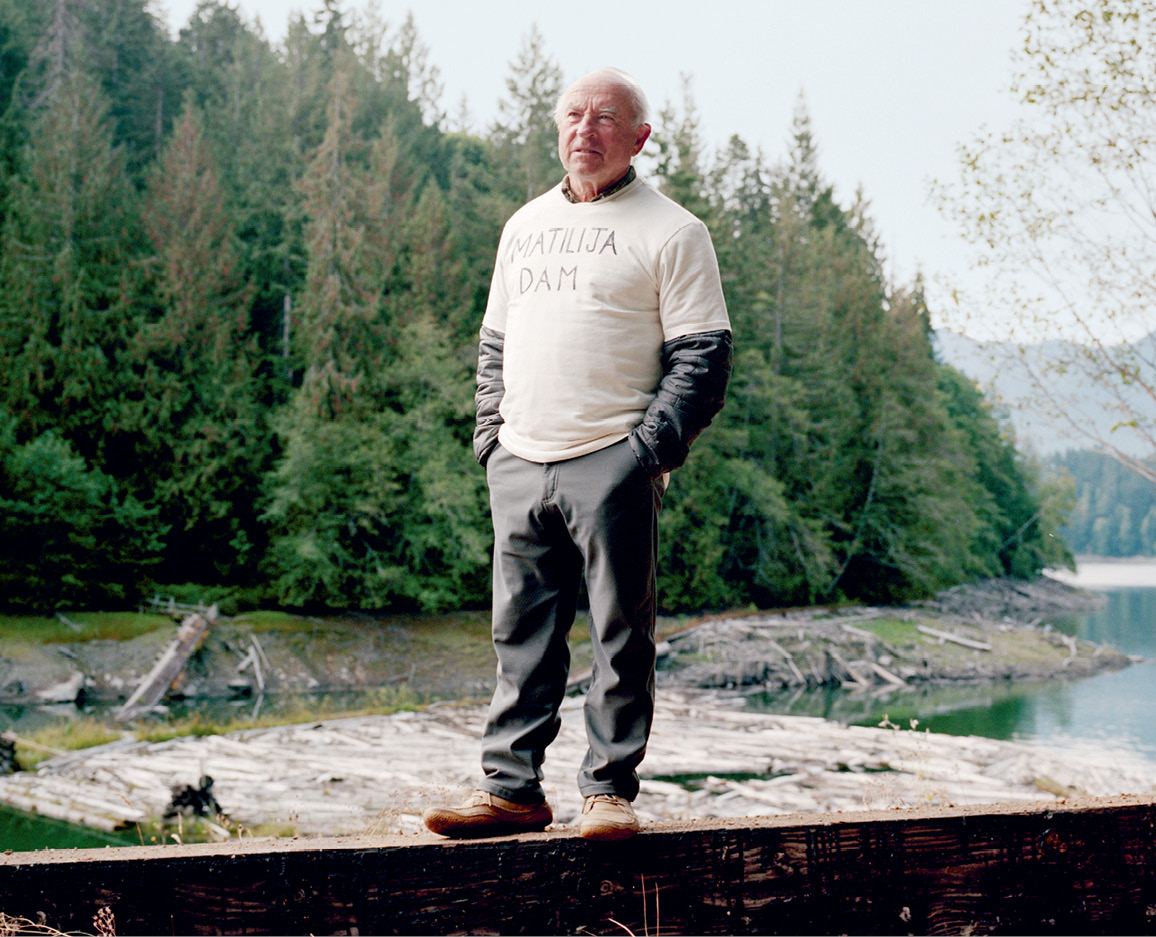

Yvon Chouinard at the Elwha Dam removal ceremony in 2011. Yvon is representing his own hometown action with his T-shirt calling for the removal of the Matilija Dam in Ventura County. Olympic Peninsula, Washington. Michael Hanson

Over the years, Ive been influenced by many nature writers like Henry David Thoreau, Rachel Carson, and Edward Abbey. I pretty much got to know what the problems were but it was lost on me what I, as one person, could do to fix them.

The first time I came to realize the power of an individual to effect major change was in the early seventies. A group of us went to our local theater to watch a surf movie. At the end, a young surfer asked the audience to attend a city council meeting to speak out against the citys plan to channel and develop the mouth of the Ventura River, one of the best surf points in the area and only five hundred yards from Patagonias office.

Several of us went to the meeting to protest the possible disruption of our surf break. We knew vaguely that the Ventura River had once been a major spawning creek for steelhead and chinook salmon. In fact, in the 1940s, the river had an annual run of four to five thousand sea-run rainbows. Then two dams were built and the water was diverted, killing the fish run and causing the bars at the mouth of the river to be starved of sand. Except for winter rains, the only water left in the river flowed from the one-stage sewage treatment plant. At the city council meeting, several city-paid experts testified that the river was dead and that channeling would have no effect on the birds and other wildlife at the estuary or on the surf break.

Then Mark Capelli, a young graduate student, gave a slide show of photos he had taken along the river, of the birds that lived in the willows, the muskrats, water snakes, and eels that spawned in the estuary. When he showed the slides of steelhead smolt, everyone stood up and cheered. Yes, several dozen steelhead still came to spawn in our dead river.

The development plan was defeated. We gave Mark office space, a mailbox, and small contributions to help fight the battle for the river. As more development plans cropped up, the Friends of the Ventura River worked to defeat them and to clean up the water and increase its flow. A second stage was added to the sewage plant and then a third. Wildlife increased and a few more steelhead began to spawn. Mark taught us two important lessons: grassroots efforts could make a difference, and degraded habitat could, with effort, be restored. Inspired by his work, we began to make regular donations to small groups working to save or restore natural habitat, rather than give the money to large, nongovernmental organizations with a big staff and overhead, and corporate connections.

There are many scientists and smart people who work tirelessly to bring us knowledge and facts, but they are too introverted or afraid of losing their jobs to champion their beliefs. Science without action is dead science. I also dont have the courage to be on the front lines, but at least Ive learned the power of activism and I want to support it.

We held our first Tools Conference in 1994 at Chico Hot Springs, Montana. We knew wed hit pay dirt when the local newspaper ran a front-page story about how we greenies asked the hotel we were staying in not to change the sheets every day to save water, a revolutionary idea at the time.

While I am often embarrassed to admit to being a businessmanIve been known to call them sleazeballsI realize that many activists could learn some of the skills that businesspeople possess. When I told that first group of activists that they were businesspeople, there was some snickering in the group. They all thought business was the enemy. I told them that their little NGOs had expenses, did marketing, and had to follow budgets: they had all the problems of business. At that time, many universities had schools of business that had no classes in environmental responsibility, and the schools of environmental studies had no classes in business. I thought I would bring some activists together with purposeful people who knew about strategic planning, community organizing, technology, and money.

Participants from the 2015 Tools Conference. Fallen Leaf Lake, California. Amy Kumler

Now, twenty-one years later, the Tools Conference has really come into its own. Every two years, we bring together 100 activists at Stanford Sierra Camp on Fallen Leaf Lake near South Lake Tahoe and let them feast on what the best trainers available in their fields can give them: grassroots organizing, lobbying, planning strategy and communications, getting the most out of social media, fundraising, using Google tools, and how to work with business. And we dont just bring in good trainers, we bring in the best.

Next page

A howling coyote answers a call from the valley below. Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. Florian Schulz

A howling coyote answers a call from the valley below. Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. Florian Schulz Greenpeace activists hang a banner off the Prospect Point observation tower above Niagara Falls to protest forest destruction, ca. 1998. New York. Joe Traver/Greenpeace

Greenpeace activists hang a banner off the Prospect Point observation tower above Niagara Falls to protest forest destruction, ca. 1998. New York. Joe Traver/Greenpeace 2:30 a.m. on the Matilija Dam, with another 100 feet of dotted line left to paint. California. DamNation Collection

2:30 a.m. on the Matilija Dam, with another 100 feet of dotted line left to paint. California. DamNation Collection

Riders in the 2007 Cabalgata Patagonia Sin Represas (Horseback Ride for a Patagonia Without Dams) protest HidroAysn and its plan to put five massive hydroelectric dams on the Ro Baker and Ro Pascua, Chile. Henry Tarmy

Riders in the 2007 Cabalgata Patagonia Sin Represas (Horseback Ride for a Patagonia Without Dams) protest HidroAysn and its plan to put five massive hydroelectric dams on the Ro Baker and Ro Pascua, Chile. Henry Tarmy The confluence of the Ro Baker and the Ro Nef, Aysn, Chile. Ross Donihue/Marty Schnure

The confluence of the Ro Baker and the Ro Nef, Aysn, Chile. Ross Donihue/Marty Schnure Mark Capelli fishing for southern steelhead in the Ventura River, ca. 1978. Ventura, California. Photo Courtesy of Mark Capelli

Mark Capelli fishing for southern steelhead in the Ventura River, ca. 1978. Ventura, California. Photo Courtesy of Mark Capelli Aerial view of the mouth of the Ventura River in 2014. Ventura, California. Rick Wilborn

Aerial view of the mouth of the Ventura River in 2014. Ventura, California. Rick Wilborn Yvon Chouinard at the Elwha Dam removal ceremony in 2011. Yvon is representing his own hometown action with his T-shirt calling for the removal of the Matilija Dam in Ventura County. Olympic Peninsula, Washington. Michael Hanson

Yvon Chouinard at the Elwha Dam removal ceremony in 2011. Yvon is representing his own hometown action with his T-shirt calling for the removal of the Matilija Dam in Ventura County. Olympic Peninsula, Washington. Michael Hanson Participants from the 2015 Tools Conference. Fallen Leaf Lake, California. Amy Kumler

Participants from the 2015 Tools Conference. Fallen Leaf Lake, California. Amy Kumler