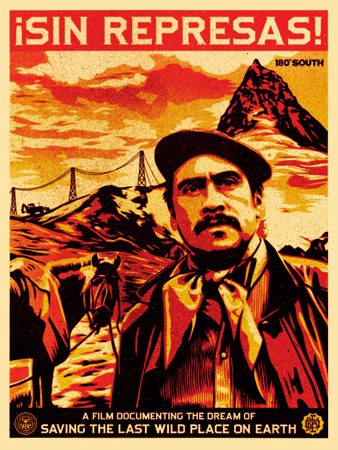

One of the biggest social and environmental issues facing Chile is the damming of rivers. Local residents have started a campaign against the dams called Sin Represas! (Without Dams). Money from Patagonias sale of a poster and T-shirt (art shown here) will be donated to charitable organizations connected to !Sin Represas! Art: Shepard Fairey

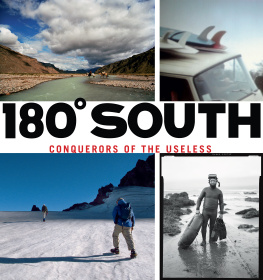

FUN HOGS

YVON CHOUINARD

Yvon Chouinard aboard the Cahuelmo. Chaitn, Chile. Photo: Jeff Johnson

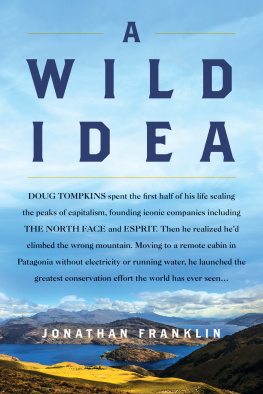

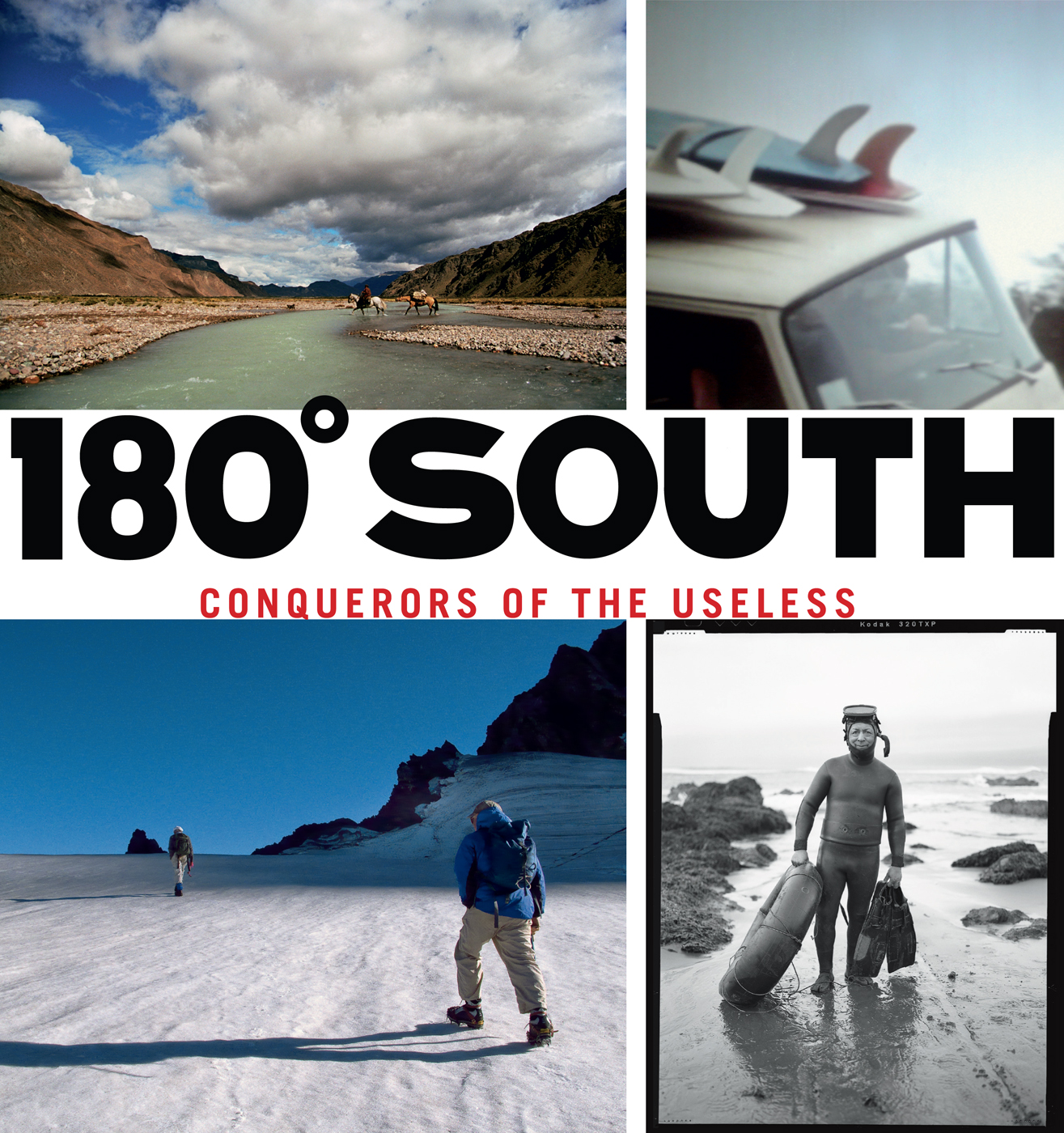

You never know how an adventure will influence the rest of your life. In 1968, when Doug Tompkins proposed that we drive from California to Patagonia in those days a name as remote and alluring as Timbuktu neither of us could know it would be the most important trip either of us would ever take. The goal was to put up a new route on an obscure tusk of granite called Cerro Fitz Roy and have some fun along the way. The experience led to an unlikely fate for a couple of dirtbags: we became philanthropists.

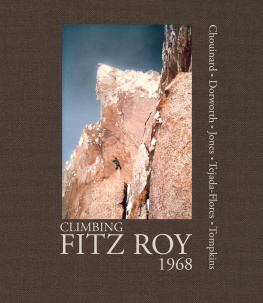

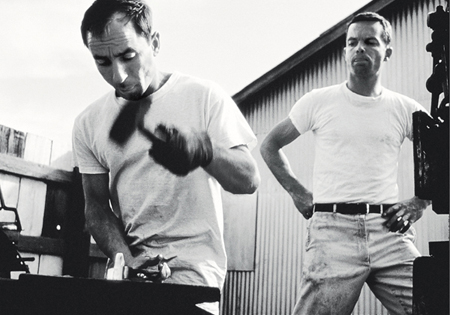

Doug owned a small outdoor store in San Francisco, where he had a few sleeping bags and tents sewn in the back room; I had a blacksmith shop in Ventura where we forged pitons and machined carabiners for a market that needed no research we and our friends were the customers.

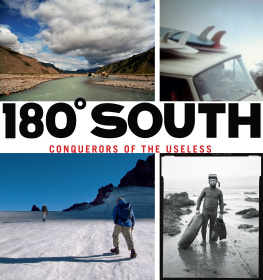

It took Doug and me only a couple of weeks to turn our work over to others, talk Dick Dorworth and Lito Tejada-Flores into driving down with us (English climber Chris Jones would hook up with us later), and secure a van a high-mileage 1965 Ford Econoline. I built a sleeping platform in the back, and then we shoehorned in four pairs of skis, eight climbing ropes, racks of carabiners and pitons, camping gear, cold-weather clothing, warm-weather clothing, wetsuits, and fishing rods. We tied two surfboards on the roof. We took along the banner Dougs wife, Susie, made for us to fly from Fitz Roys summit; its big block letters read VIVA LOS FUN HOGS.

We all had complementary talents. Because I had taken auto mechanics in high school, I was appointed team mechanic. Doug and I were the most experienced climbers; Doug and Dick were expert skiers. I was a surfer, and Lito was a climber and photographer to whom we assigned the task of documenting the trip with a wind-up 16mm Bolex we bought secondhand. Lito had never before made a movie or even shot a movie camera. We were living up to Dougs credo, borrowed from Napoleon, Commit first, then figure it out.

Only a week after leaving Ventura, we were surfing the breaks outside Mazatln. South of Mexico City the pavement gave way to a dirt road that, except for a few concrete stretches through capital cities and a gap in Panama, would continue to Patagonia. Once we crossed into Guatemala, however, we confronted a challenge greater than a dirt highway. We were sleeping on the ground around the van when an army patrol woke us, a 16-year-old kid pointing his machine gun from my head to Dicks. We managed to convince them we werent CIA agents, just tourists on a surf trip, then made a beeline for the border of Costa Rica, which had the only sane government in the region and great surf breaks.

We had to scuttle our plan to stay there for a while when the volcano above our break erupted. So much ash fell between sets that the decks of our surfboards turned black and it was almost impossible to breathe.

Tom Frost and Yvon Chouinard at the forge in the early years. Ventura, California. Photo: Patagonia Archives

We drove south to Panama to ride breaks that probably had never been surfed before, and then, to get around the roadless Darin Gap, drove our van onboard a Spanish freighter bound for Cartagena, Colombia. Dick, famous for his night driving skills and aided by cassette tapes of Joplin, Dylan, and Hendrix, and a few other means power-drove all the way to Ecuador, where I knew of a surf spot Mike Doyle had discovered.

All this time Lito filmed our adventure with the wind-up Bolex. Doug had talked me into sharing the costs of the camera and film with him. He was convinced that once home, we the producers could sell the film to make enough to pay for the trip and then some. (When we got back, we spent more money editing the footage into a one-hour film, Mountain of Storms, which made it into a few specialty film festivals but was never distributed.)

We surfed in Ecuador, then sold our boards in Peru. In Chile we pulled out the skis and skinned up and skied down Lliama, a big volcano outside Temuco, and farther south, Osorno, sometimes called the Fuji of South America.

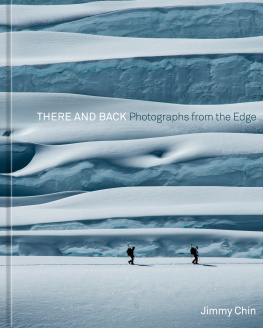

Just south of Puerto Montt the highway came to an end, blocked by deep fjords and the great tidal glaciers descending from the continental icecaps. We loaded the van on small ferries and crossed sapphire-blue lakes framed by beech forests and snow-capped volcanoes, off-loaded the van, and drove the short distance to the next lake crossing. In Argentina, on the leeward side of the Andes, the landscape changed suddenly from temperate rain forest to open steppes, and the Econoline, seasoned by over 12,000 miles of hard driving, barreled down the celebrated Route 40, the dirt road that, on the Argentinean side of the Andes, connects northern to southern Patagonia.

Miles later we left Route 40 and followed a road more like a horse track around Lago Viedma, one of a series of large, glacially carved lakes in the southern Andes. This was the worst road any of us had encountered, and we didnt see another vehicle for 180 miles. Then the trail petered out entirely. In those years only a footbridge crossed the Rio de las Vueltas, so we parked the Econoline and talked some army soldiers into helping us carry our gear to base camp. The only other humans in the region were the gaucho Rojo, and the widow Sepulveda and her sons, who ran a sheep station three days by horse from Lago del Desierto.

At that point we had been on the road for nearly four months; it would take us another two months to climb Fitz Roy. The peak had been summited only twice, first by the iconoclastic Frenchman Lionel Terray, who wrote that Fitz Roy was one of two climbs he had no desire to repeat. Terray built his reputation on ascents of peaks that were obscure to laymen but considered classics by climbers for their beauty or the difficulty of their routes. He understood that how you reached the summit was more important than the feat itself. His approach appealed to those of us who had cut our teeth on first ascents of Yosemites high walls, where you got to the top only to realize there wasnt anything there. Terray said it all when he titled his autobiography Conquistadors of the Useless.