TotinhaI adore you!

Youve made these past

four years the best of our life.

He was just not impeded by any kind of realities or practicalitiesit was like, What do you want? Dont limit your potential with a lack of imagination. If you dont think big, its never going to happen. I dont think he cared too much what other people thought. I dont think he was trying to please anybody else. And get out of my way, Im going for this vision that Ive created. And thats potent. Its heady.

QUINCEY TOMPKINS , oldest daughter of Doug Tompkins

He was fearless. He never turned his back on a difficult problem, a difficult conclusion, or an overwhelming challengean overhanging cliff on a climb, or a planet where loss of habitat and global warming were putting the future in danger. Doug never stopped, never slowed; he was the quintessential man of actiona force of nature, for nature.

LITO TEJADA-FLORES , filmmaker and climber

At the summit, we got nailed by this huge ice storm, and Doug thought he knew the way down and started leading us. Suddenly he stopped. He froze. He was at the edge of a precipice a thousand feet down. He was completely wrong. Then I pulled a compass outwhat I call a Boy Scout compass. We were 180 degrees off and Yvon Chouinard gets right up in my face and said, Isnt this great! Makes the whole trip worth it! And I am thinking, What kind of maniacs am I with?

TOM BROKAW , NBC television anchorman, author of The Greatest Generation

Doug learned fast; he felt like he was invincible because the normal amounts of risk didnt apply to him. If you ever flew with Doug in his plane, youd know what I mean. He took us on a flight over Patagonia, and it was all I could do to keep my stomach down. He would set it on one wing and spin around and around looking at something. He clearly had that quick-twitch, fighter-pilot stuff.

DAVE SHORE , rafting guide

Contents

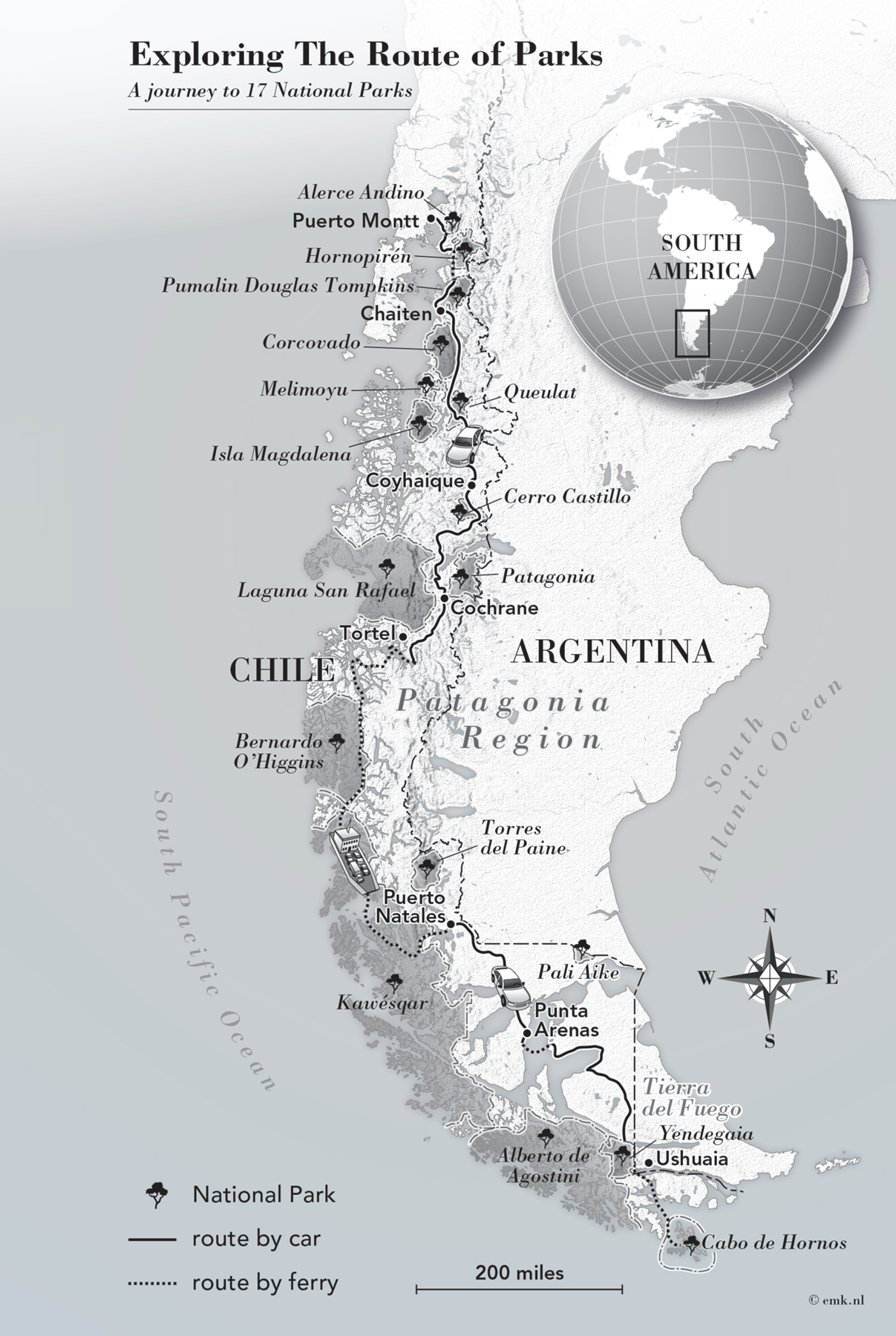

I lived many years in awe of Doug Tompkins. Hed done the impossibleclimbed to the heights of corporate America and then cashed in his chips, taken his millions, and fought for nature. I admired his fight for native forests, grasslands, rivers, and wetlands. I visited many of the remarkable national parks he created in South America. When my Uruguayan friend Rafa called to tell me that Doug had died in a kayak accident in December 2015, I immediately felt like an idiot. How had I not spent more time with this genius in my midst? How had I only interviewed him a half-dozen times in his last ten years?

As I set off to write this book I sought to capture the essence of his remarkable life, and I felt qualified for the challenge. My passion for the great outdoors set in earlybouldering in New Hampshire and swamp exploring in Massachusetts. Like Doug, I was a downhill ski racer and loved testing the limits of speed and control. Doug took his passions to San Francisco, then in 1989 flew down to southern Chile. I too followed a similar path, traveling from San Francisco in 1989 to explore southern Chile by mountain bike. Like Doug, I have spent half my life in the United States and half in South America.

When I first queried Kris Tompkins for permission to write a book about her late husband Doug, I knew I didnt have to ask. In fact, she confirmed that when she told me, You dont need my okay; you can just go and write it. Kris was right, but that was never the book I wanted to create. I was interested in the inside story of a remarkable man. I interviewed Doug enough during my nineteen years reporting for The Guardian to know his close friends were protective and almost tribal in their secrecy. Then Kris said no. They couldnt help me on the book. Eight months later, I asked Kris again for her permission and collaboration. Again I was told no. Kris was too busy.

I tried again. If she didnt have the time, could she at least give her blessing? Could we agree to walk separately down the same path? The biography would not be authorized but collaborative. We could share notes, impressions, and stories in the wake of her husbands shocking death. Here we found a common ground that, after two years, blossomed into a collaboration beyond my imagination and eventually hours of face-to-face conversations with Kris.

Kris received my calls, read my emails, gave long interviews in Valle Chacabuco and Pumaln Park in Chile, met with me in Rincon del Socorro in Argentina, and, as I was finishing the book, made time for video calls from her home in California. She shared Dougs love notes, private emails, personal photo collection, and stories of their life together. She shared his passion for conservation and was generous in sharing his life with me.

For nearly four years, I explored the world of Doug Tompkins. At his park in Patagonia I took an afternoon walk through Chacabuco Valley, aware that wild pumas roamed nearby. Instead of scary it was invigorating; a sense of longing awoke inside meas if I needed a reminder that humans too are part of the food chain.

While visiting the national parks Doug had established in Argentina, I could hear but not see a family of howler monkeys high in the trees. My seven-year-old daughter, Akira, mimicked the call and the howlers descended, curious about this strange little monkeyroughly their size. For minutes they stared eye to eye at one another, calling back and forth. Akira continued mimicking monkey talk, and the howlers chattered among themselves excitedly as they discussed the meaning of this new voice in the woods. Everyone present felt the connection, the communicating, the communion. I had brought my children on the reporting trip hoping that in the wild spots that Doug Tompkins saved perhaps some wild would rub off. Might they return home themselves rewilded? Akiras encounter with the howlers made it all seem possible.

This book is my journey into one mans love affair with the wild. The wild mountains, forests, and rivers. Doug Tompkins was also wild. Competitive, hyperactive, and as flawed as his friend and neighbor Steve Jobs, with whom he argued at parties. Tompkins was an environmentalist who drove a red Ferrari. A multimillionaire who preferred to sleep on a friends couch. He was a stickler for details, yet he hardly noticed his two daughters right before his eyes. Hard-nosed, arrogant, and argumentative, he despised compromise.

The world for Doug Tompkins was black and green: you were either a scourge or a seedling. He never seemed to worry what others thought. When the media savaged him, Tompkins laughed. He told Thomas Kimber, a young entrepreneur who was his neighbor, It doesnt matter; in fifty years they will be building statues of me.

Like the way he drove cars and paddled kayaks, Doug Tompkins rarely looked back. Yet, for all his faults, I found myself transfixed by this rock climber who at the age of forty-nine and atop the peak of capitalism took a deep look around and admitted to himself, Ive climbed the wrong mountain.

To understand this complex man, I conducted roughly 165 interviews ranging from his seventh-grade classmate Stone Ermentrout to his lifelong friend Yvon Chouinard. I sat for interviews with Susie, his first wife; both his daughters; and dozens of employees who loved him plus a half dozen who loathed him. Notably, by the time of his death, Tompkins had converted many adversaries into allies. Critics who thought he was exaggerating the demise of planet Earthpeople who wondered what he meant when he said that extinction was the mother of all crisisbegan to see that he had offered them not a doomsday scenario but a glimpse of the future.