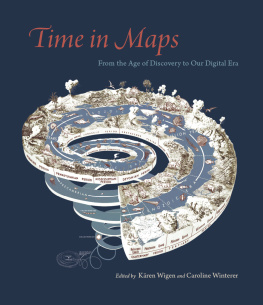

Caroline Winterer - Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era

Here you can read online Caroline Winterer - Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: University of Chicago Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

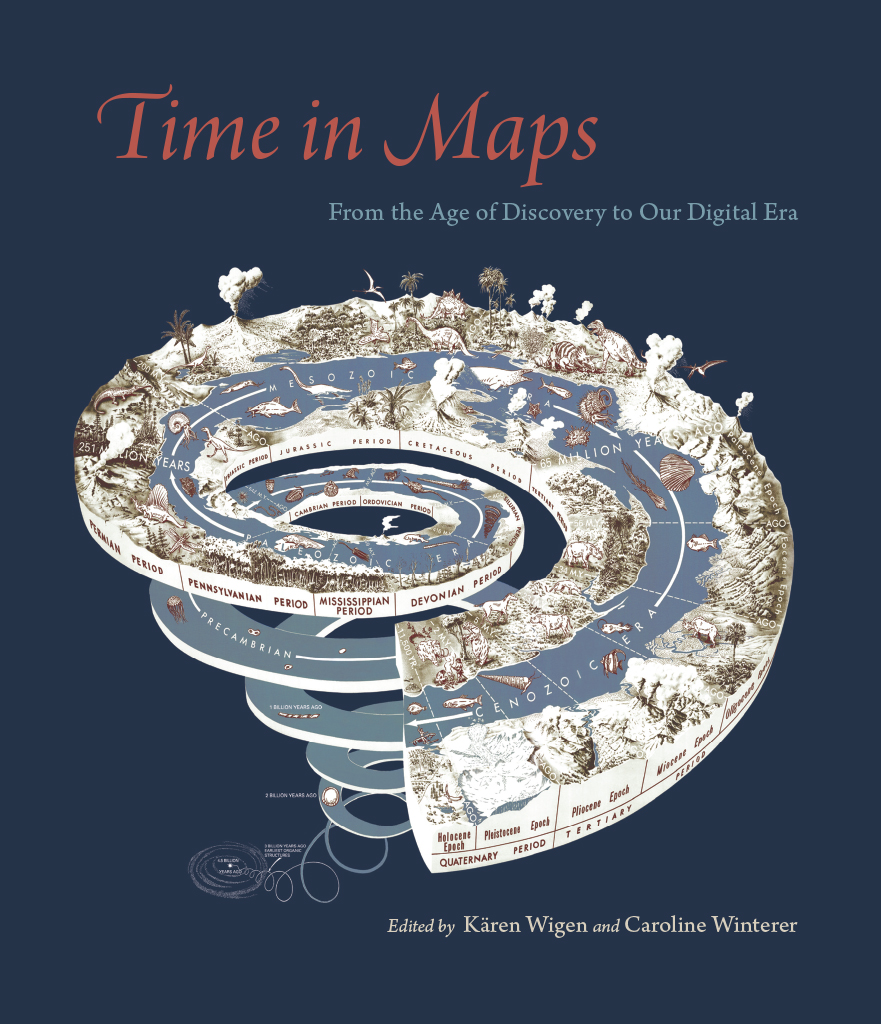

- Book:Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Chicago Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Edited by Kren Wigen and Caroline Winterer

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago & London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in Canada

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

isbn-13: 978-0-226-71859-0 (cloth)

isbn-13: 978-0-226-71862-0 (e-book)

doi: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226718620.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wigen, Kren, 1958- editor. | Winterer, Caroline, 1966- editor. | David Rumsey Map Center, host institution.

Title: Time in maps : from the Age of Discovery to our digital era / edited by Kren Wigen and Caroline Winterer.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2020. |Papers from a conference held at the David Rumsey Map Center at Stanford University in December 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019057905 | ISBN 9780226718590 (cloth) | ISBN9780226718620 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: CartographyHistoryCongresses. | Time in cartographyCongresses | LCGFT: Conference papers and proceedings.

Classification: LCC GA108.7 .T56 2020 | DDC 912.09dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019057905

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Elizabeth Fischbach and John Mustain

: : Caroline Winterer and Kren Wigen

: : William Rankin

: : Kren Wigen

: : Richard A. Pegg

: : Barbara E. Mundy

: : Veronica Della Dora

: : Daniel Rosenberg

: : Caroline Winterer

: : Susan Schulten

: : James R. Akerman

Abby Smith Rumsey

We all know where we arenearing the end of the second decade of the twenty-first century. Philosophers may argue that time is a mental construct, but our bodies know better. Time is a place we inhabit. How do we know where we are? The same way mammals and birds do. We process information through the hippocampus, a small seahorse-shaped organ in the brain that maps our perceptions onto a grid composed of cunningly named place cells. As for time, the body has its own internally generated clock that responds to cues from external stimulilight, temperature, smell, and so on. From these time and space coordinates, we conjure a mental model of the world by which we navigate our environment.

It is no wonder that all cultures create practices that mark time and space. Humans tell themselves where they come from as a way of knowing who they are and where they belong. Nor is it surprising that their temporospatial imaginations vary greatly across time. At the Time in Space conference, presentations ranged from the late Aztec period to the early modern Japanese and twentieth-century American tourist maps. The fruitfulness of the ensuing conversations, well reflected in this volume, demonstrates how much more there is to know about the past as we learn to read the evidence in map archives.

Historians write about the past from documentary evidence produced by cultures with writing systems whose documents survive and are made accessible through archives and librarieslamentably, a fractional record of human consciousness. Until recently maps have been marginalized by the profession that trains its experts in textual but not visual analysis. Libraries and archives that serve historians rarely ease access to maps through item-level cataloging, let alone by recording each map in an atlas.

Digital technologies have changed all that. Decades ago, the development of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) heralded a new engagement with mapping and primed our appetite for more. We now have unprecedented online access to cartographic sources through high-resolution images accompanied by rich metadata and an expanding suite of tools for magnification, geo-referencing, overlays, timelines, and animations, among others. Analog maps and globes have been recovered as core historical documents, and historians are learning how to read and interpret them on their own terms, not as derivative or illustrative objects and not just as subjects to be theorized. Like other documentary forms, cartography uses specific tools of representationcompression and scale, color and font, symbology and iconography, global views and insetsall placed within one frame that reveals what is otherwise obscured by noise. Cartographers practice of collapsing three dimensions into twoflat mapsor reducing three dimensions to miniatureglobesare brilliant cognitive sleights of hand whereby too much information is rendered legible.

GIS deploys new forms of representation, such as layering data and dynamic mapping. But historians here point out that GIS-derived animated timelines showing change over time emphasize the linearity of a narrative, always within the framework of before and after. Printed maps are necessarily static and allow our attention to linger, dilate, and roam over all the contents within the framea very different cognitive mode. These essays argue that such maps are agents of thought, generative of new cognitive modes.

Conference participants were struck by how powerfully maps can represent ideas, things seemingly immaterial that nonetheless leave traces all across the landscape. Ideas wear the guise of metaphors such as veils pulled back to uncover knowledge, trees of time with many branches, rivers of influence and exchange, footprints as synecdoche signifying the traversal of time. They reinforce the notion that our experience of time and space is fundamentally grounded in the physicalour bodies and what they perceive.

The essayists grapple forthrightly with the teleologies of historical maps. In particular they call out our contemporary biases against both sacred chronologies of sin and salvation and secular tales of progress toward enlightenment or Manifest Destiny. The scholars ask what maps can and cannot represent (as opposed to illustrate), how they do so, and how they fail. Good mapmakers know that compression and abstraction, if done sloppily, tend to emphasize novelty and technique for their own sake (perhaps colors too bright or type too bold) while failing to accurately represent context or relationships of distance, topography, and contiguity. Examination of failed maps was among the highlights of the conference, incidentally. The presenters offered keen insights into the normally invisible mechanics of cartographic time and space.

Maps establish the context through which we perceive associations. They can prompt us to infer causality, even if the inference is unintended, misleading, or signified something quite different then to its audience than it does now to us. Data visualization maps, though, such as the justly renowned Charles-Joseph Minard 1869 flow map, Figurative Map of the successive losses in men of the French Army in the Russian campaign 18121813, are designed to associate effect with cause. By specifying calendar time and local temperatures on the ground, Minard as good as states that the unimaginable loss of life was due to the severity of the Russian winter. The map refrains from suggesting why the campaign was conducted in winter. Its verbal restraint and visual clarity invite us to ponder the horror and draw our own conclusions. Thus it makes what is unimaginable self-evident.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era»

Look at similar books to Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.