J. Devika

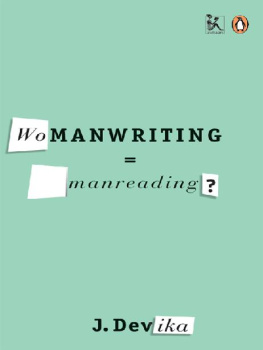

WOMANWRITING = MANREADING?

Contents

ZUBAANPENGUIN BOOKS

WOMANWRITING = MANREADING?

J. Devika has written on the intertwined histories of gender, culture, politics and development in her home state, Kerala. She is bilingual and translates both fiction and non-fiction between Malayalam and English, and also writes on contemporary Kerala on www.kafila.org. She currently teaches and researches in the Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram.

The Triumph (and the Harrumph) of the Malayalee Male Critic

SEIZING AN OPPORTUNITY

The present is a strategically important time for feminist literary criticism in Malayalam. Since the 1990s, the concept of the national-popular forged by the mainstream political left in the 1950s has been under severe strain. This was not only because of liberalization and the rise of consumerism precipitated by the migration of Malayalees (speakers of Malayalam, the language of Kerala) to the Gulf since the early 1970s, but also because of the increasingly strident voices of excluded social groupsDalits, Adivasis, women and others. Feminism, however, has increasingly faced rough weather. The reservation of 33 per cent seats for women in the three-tier Panchayati Raj system and the special focus on women as agents of development in local-level planning in the mid-1990s ensured the hegemony of a certain version of liberal feminism by the state; in the same period, feminists in Kerala fought long, tiring battles over sexual violence against powerful members and adherents of political parties (Devika and Kodoth 2001). Feminism was increasingly pluralized in the 1990s, but mainstream feminists remained suspicious of criticisms of elitism among feminists.

Perhaps the only field in which the feminist perspective made steady gains was literature. The rise of women authors writing against patriarchy in Malayalam was paralleled by the slow but steady loss of intellectual legitimacy suffered by liberal humanist literary criticism since the 1990s. In the past three decades, the numbers of women authors have gone up in the major genres. They have also won many of the most important literary prizes; many are bestselling authors. Not surprisingly, we find that in surveys of contemporary Malayalam literature, womens anti-patriarchal writing (much of which is explicitly feminist) is frequently hailed as a promising developmentfrom different political perspectives. Thus the well-known poet and radical left critic Satchidanandan referred to it as the most powerful avant-garde in contemporary Malayalam literature (2002:817); the essays in the volume Pennezhuthu (Womanwriting) (Jayakrishnan 2002) try to reconcile it with liberal humanism. It has received acceptance within standard literary history too (for example, Pillai 2009). There is also acceptance of the relevance of feminist literary criticism in Malayalam among leading male literary critics (Vijayan 1992; Raveendran 1997, 2002; Prabhakaran 2002; Pokker 2002; Rajakrishnan 2006; Tharamel 2008).

However, it seems that more has to be done, and urgently, if we want to preserve the mileage gained. This became apparent to me while taking part in a TV talk show in 2009 on the proposed reservation of 50 per cent seats in the Panchayati Raj system for women in Kerala, to which I had been invited as one of four guest speakers. I had been invited as a feminist researcher writing on politics and gender in contemporary Kerala. The other female guest was a young woman politician, associated with the Communist Party of India (Marxist) who had been active in Keralas political decentralization. There were two male guests too, who, however, displayed no direct interest in the topic to be discussed. Indeed, as we soon learned, they had no views at all on it. However, they possessed a passport of a different sort which allowed them immediate entry into any kind of public discussion in Keralaone of them was a well-known literary author, the winner of prestigious literary prizes in Malayalam, and the other, an aesthete. In other words, direct or indirect participation in the literary world is a magic talisman that opens the doors of the publicmostly to men, though women in the past few decades have fought for and sometimes gained (partial and/or gendered) entry. And it is well known by now that Keralas public is emphatically masculinist and mostly male.

What set me thinking was not so much their vulgar display of masculine hubris in the discussion, as their apparently unshakeable sense of entitlement as possessors of refined aesthetic sensibilities to issue true statements on womenon womens ostensibly essential natures, social condition, abilities, inclinations, preferences and weaknesses. Persistent efforts to point out empirical errors, logical fallacies and the effects of rhetoric in their argument about womens essential incapacity for public life did not even make a dent in their confidence about their knowledge of women. The contrast between the woman politician and woman researcher on one side, and the male literary genius and male aesthete on the other, could not be more glaring: the former clearly struggling for full citizenship and voice and the latter, convinced of their superior refinement, determined to exclude women in general from full citizenship. The members of the Purushapeedhana Parihaara Vedi (Forum to Resolve the Oppression of Men) in the audience turned out to be the most ardent supporters of the genius and his companion; their misogyny blended with such seamless perfection that it almost echoed the intensely masculine insecurities of Malayalee modernism which the genius represented.

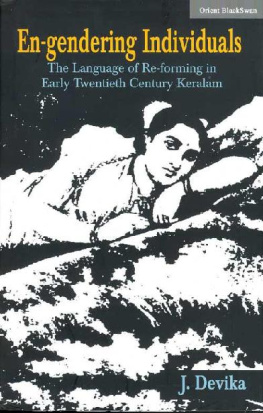

My earlier research into the history of modern gender in early-twentieth-century Kerala allowed me to connect this unshakeable sense of masculine power with a key feature of the early history of social and community reformism in Keralathe power of Reformer-Man (Devika 2007). There was broad consensus among the advocates of social change of this period that reconstituting social life in terms of modern gender relations required the institution of a non-reversible relation of power between those who came into contact with the norms and mores of modern society earlier and those who could not. The former were of course more likely to be men and the latter, women. The Reformer-Mans power was widely accepted by the early twentieth century as an indispensable condition for the realization of the projected alternative to the prevailing social order based on caste difference and inequality: a society organized by modern gender. To me, the privileged male members of the upper echelons of the contemporary literary field seem to be claiming, very comfortably, Reformer-Mans authority over women and their matters, in full confidence of the non-reversibility of that relationship.

Indeed, this took me back to fairly recent debates in Kerala over the significance of marginal peoples writing and their claim to the status of literary author. The most heated of these was around the autobiography of a sex worker, Nalini Jameela, which appeared in 2005 and became an all-time bestseller in Malayalam. Many leading writersnot necessarily bearers of conservative political labelsexpressed outrage against the media attention the book received, expressing explicit concern about the danger it posed. The book, they claimed, would hamper Malayalee peoples aesthetic education and disrupt the social function of literature. That is, books like Jameelas would not, apparently, achieve the aesthetic culturing of readers, the transformation of readers into self-governing liberal subjects.