Contents

This eBook is licensed to Simon Karoly, simonkaroly123@gmail.com on 03/17/2021

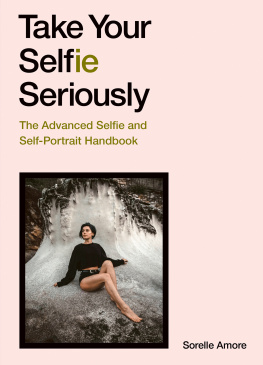

The World in a Selfie

This eBook is licensed to Simon Karoly, simonkaroly123@gmail.com on 03/17/2021

The World in a Selfie

An Inquiry into the

Tourist Age

Marco DEramo

This eBook is licensed to Simon Karoly, simonkaroly123@gmail.com on 03/17/2021

This English-language edition first published by Verso 2021

First published as Il selfie del mondo

Feltrinelli 2017

Translation Bethan Bowett-Jones and David Broder 2021

An earlier version of Chapter 8 appeared as UNESCOcide,

in New Left Review, no. 88, JulyAugust 2014.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-107-2

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-110-2 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-109-6 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: DEramo, Marco, 1947author.

Title: The world in a selfie: an inquiry into the tourist age / Marco DEramo; translated by Bethan Bowett-Jones and David Broder.

Other titles: Il selfie del mondo. English

Description: First English-language Edition Hardback. | Brooklyn: Verso is the imprint of New Left Books, 2021. | Series: Campi del sapere | First published: Milano: Feltrinelli, 2017, under title Il selfie del mondo. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: The World in a Selfie offers a spirited critique of the cultural politics of a tourist age. Tourism is not just the most important industry of our century, generating huge waves of people and capital, calling forth a dedicated infrastructure, and upsetting and repurposing the architecture and topography of our cities. It also encapsulates the problem of modernity: the search for authenticity in a world of ersatz pleasures Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020045101 (print) | LCCN 2020045102 (ebook) | ISBN 9781788731072 (Hardback) | ISBN 9781788731102 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Tourism Social aspects. | Tourism.

Classification: LCC G156.5.S63 D4713 2021 (print) | LCC G156.5.S63 (ebook) | DDC 306.4/819 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020045101

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020045102

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays

This eBook is licensed to Simon Karoly, simonkaroly123@gmail.com on 03/17/2021

Contents

This eBook is licensed to Simon Karoly, simonkaroly123@gmail.com on 03/17/2021

April 2020, a metropolis of your choice: Paris, New York, London, Barcelona, Berlin, San Francisco, Rome, Moscow. Your city is a metaphysical painting by de Chirico. It is deserted, streets empty, monuments and skyscrapers petrified, stripped naked by the absence of traffic, buses, pedestrians. We, the inhabitants, locked up in our homes, visit it on TV screens, on monitors, on mobile phones. How much would we give to experience it in person! To walk it in solitude, to feel it, to imbibe it in silence.

But we cant. We are confined to our homes by the coronavirus pandemic, all of us longing for the city out there, a city finally restored, like weve never seen it before.

This was the common experience of urban residents over much of the planet. It was a fleeting experience, soon to be forgotten. But in those months it seemed irreversible to the citizens of half the world.

Even locked in our homes, the gaze we turned on our own cities was touristic, for the city that flashed onto our screens in our confinement fulfilled the dream of every tourist a place without other tourists, which is to say: without ourselves. The cities emptied by the virus were analogous to the pristine Caribbean beaches of the travel brochures. And yet, they are unreachable, because the moment we the confined are able to dive into the city again, it will immediately be degraded by traffic jams, crowds and our very presence.

Until then, the vast conurbations emptied by the virus are dead cities, non-cities. The shutters are closed, the meeting rooms silent, all interactions cancelled. Only the homeless occupy the sidewalks, sleeping even during the day. There is a sense of abandonment, as if some Pied Piper had taken all the residents with him.

The virus has emptied the city in the exact same way tourism usually does, when in summer the streets are abandoned by native residents fleeing to distant shores. There is an uncanny similarity between the emptiness of the tourist city and the city the virus has emptied of tourists. It shows how deeply touristic our very idea of the city is, how deeply rooted it is in our very core, how inseparable it is from our experience of urbanity.

No previous civilisation, from any century or any part of the globe, has ever known anything that could be described as a tourist city. It is a novelty peculiar to modernity or should that be, postmodernity?

Tourism belongs to that category of social phenomena, like sport or advertising, that are omnipresent, familiar, yet seldom truly explored in depth. And as with the study of sport or advertising, the bibliography of tourism studies is endless, yet finding new ideas is like looking for a needle in a haystack. Original contributions to the field can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

But tourism is even more important than sport or advertising so much so that we could quite plausibly term the current era the Age of Tourism, in the same way that we used to speak of the Age of Steel or the Age of Imperialism. Here we come to a paradox. Tourism trades in an intangible commodity; it belongs to the experience economy. The tourist is awestruck by the immensity of the Grand Canyon, by Machu Picchu at first light, by the Acropolis of Athens. But to retail such wish-fulfilments, tourism sets in motion a very prosaic infrastructure: airports and planes, railway stations and trains, hotels and food wholesalers, telecommunications and IT networks.

We are used to thinking of real industry as mining, steel manufacturing, ship and car building in short, in terms of coal, electricity and steel and so we view tourism as a kind of post-modern frill, as superstructural rather than foundational. But the truth is that tourism is the most important industry of the century.

When I presented this thesis three years ago in the first Italian edition of the book you have in your hands, I was looked at indulgently, as one who likes to exaggerate, who has a weakness for catchphrases. It is depressing that the most compelling evidence of this thesis had to be provided by a tiny virus, when the proof was already right there in front of our eyes.

Why hadnt tourisms importance fully registered before the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdowns? Because tourists themselves are hard to take seriously. They are often comically dressed, literally out of place, walking in mountain boots in the middle of the city, wearing ridiculous baseball caps alongside business-people in suits. Its hard to take tourists seriously.

And yet the tourism industry was worth 8,800 billion US dollars in 2018 (10.4 per cent of global GDP, or one and a half times the GDP of Japan, the third largest economy on the planet) and supported 319 million jobs (10 per cent of global employment).