Table of Contents

Commonwealth of Australia 2021

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced or distributed by any process or stored in any retrieval system or data base without prior written permission from the copyright holder. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to:

| Postal Address: | Australian Biological Resources Study | Email: |

| GPO Box 858 |

| Canberra ACT 2601 |

| Australia |

| Editor | Tony Orchard |

| Assistant Editors | Brigitte Kuchlmayr, Annabel Wheeler |

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government, the Portfolio Ministers for the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) or CSIRO Publishing.

While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth, CSIRO and CSIRO Publishing do not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication.

This book is available from:

| Postal Address: | CSIRO Publishing | Tel: | +61 3 9545 8400 |

| Locked Bag 10 | Email: |

| Clayton South VIC 3169 | Web: | www.publish.csiro.au |

| Australia |

This work may be cited as:

Steven L. Stephenson, Secretive Slime Moulds. Myxomycetes of Australia. ABRS, Canberra; CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne (2021).

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

| ISBN | 978 1 486 31413 3 (hbk) |

| 978 1 486 31414 0 (epdf) |

| 978 1 486 31415 7 (epub) |

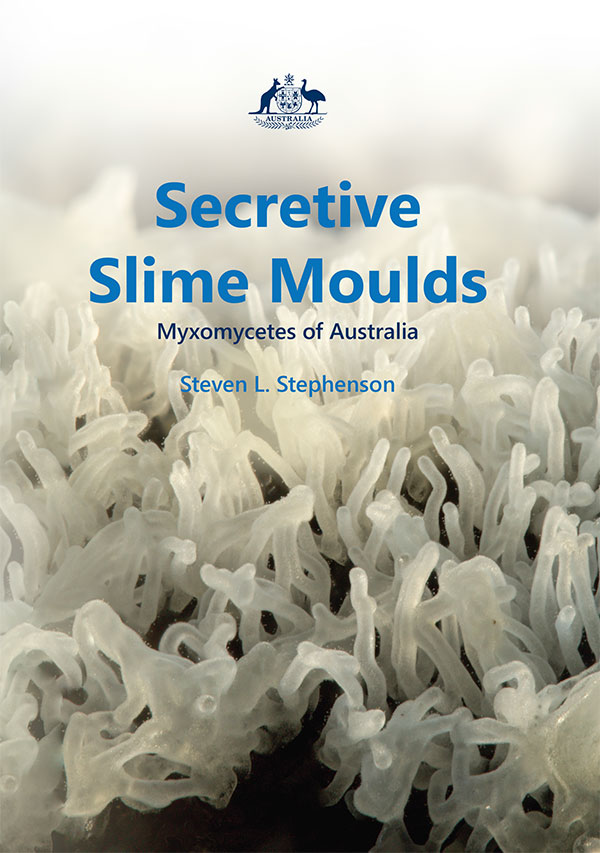

Cover Photographs

| Front and background: | Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa P. Vallier |

| Back cover (top to bottom): | Arcyria cinerea P. Vallier |

| Cribraria mirabilis S. Lloyd |

| Physarum roseum T. & J. Van der Heul |

| Cover designer: | Brigitte Kuchlmayr |

Published by ABRS, Canberra & CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne

Printed in Australia by Courtney Colour

Contents

Dr Steven L. Stephenson, Research Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701, United States of America.

Illustrators

Dmitry Leontyev, Department of Botany, H. S. Skovoroda Kharkiv National Pedagogical University, Valentynivska 2, Kharkiv 61168, Ukraine.

Angela Mele, 4038 Cleveland Ave, Apt. 2E, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, United States of America.

Photographers

Peter & Elaine Davison, 148 Bateman Road, Mt Pleasant, Western Australia 6153, Australia.

Bruce Fuhrer, 25 Sunhill Avenue, Ringwood Victoria 3134, Australia.

Teresa & John Van der Heul, 84 Noble Parade, Dalmeny, New South Wales 2546, Australia.

Heino Lepp, PO Box 38, Belconnen, Australian Capital Territory 2616, Australia.

Sarah Lloyd, 206 Denmans Road, Birralee, Tasmania 7303, Australia.

Gabriel Moreno, Edificio Biologa, Fac. Ciencias, Dpt. Ciencias de la Vida (Botnica), Univ. Alcal, 28805 Alcal de Henares, Madrid, Spain.

Yura Novozhilov, Laboratory of Systematics and Geography of Fungi, Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 197376, St. Petersburg, Str. Prof. Popov, 2, Russia.

John Shadwick, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701, United States of America.

Paul Vallier, 119 Old Maryborough Road, Gympie, Queensland 4570, Australia.

Steve Young, Steve Young Photography, Korora (Coffs Harbour), New South Wales 2450, Australia.

Preliminary pages illustrations: Angela Mele:

page i:Badhamia foliicola

page iii:Cribraria cancellata

page iv: Perichaena vermicularis

page v:Diachea leucopodia

page vi:Stemonitis fusca

Myxomycetes (also known as plasmodial slime moulds or myxogastrids) have been known from their fruiting bodies since at least the middle of the seventeenth century, when the first recognizable description of a member of the group (the very common species now known as Lycogala epidendrum) was provided by the German mycologist Thomas Panckow (). However, since the fruiting bodies produced by some species of myxomycetes can achieve considerable size (those of Fuligoseptica commonly exceed 10 cm or more in total extent), there is little doubt that myxomycetes have been observed in nature as long as mankind has existed. Evidence from molecular studies indicates that myxomycetes have a long evolutionary history and probably were present on the earth several hundred million years ago. Myxomycetes do not have a particularly attractive name, but many examples produce fruiting bodies that are miniature objects of considerable beauty. However, because of their small size, all but the largest and most conspicuous examples tend to be overlooked in nature.

Since their discovery, myxomycetes have been variously classified as plants, animals or fungi ( more than 185 years ago, is derived from the words myxa (meaning slime) and mycetes (referring to fungi). However, myxomycetes are profoundly different from the true fungi and actually belong to another kingdom, the Protista (sometimes called Protoctista).

Approximately 1000 species of myxomycetes have been described to date (

The fact that the vast majority of myxomycetes can be assigned to one of two groups on the basis of the spore colour in mass is not a new concept. It was first proposed by Joszef ). The 1925 edition is noteworthy in the context of the present monograph because it contains references to species of myxomycetes that had been reported from Australia prior to the third decade of the twentieth century.

The first report of myxomycetes from Australia was by the Reverend Miles ) relating to myxomycetes appeared during the major portion of the second half of the twentieth century. Only one of these (Ing & Spooner, who reported 16 species) mentioned more than a few species.

The first truly comprehensive checklist of the myxomycetes of Australia (). Moreover, a number of specimens collected in Australia are problematic and have not yet been assigned to any currently recognized species. In some cases, these probably represent incompletely developed or aberrant specimens, but in some instances it is likely that they are undescribed species.