How to Reform

Capitalism

The School of Life

Other books in this series:

Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person

On Confidence

Why We Hate Cheap Things

How to Find Love

Self-Knowledge

The Sorrows of Work

The Sorrows of Love

How to Reform

Capitalism

The School of Life

Published in 2017 by The School of Life

70 Marchmont Street, London WC1N 1AB

Copyright The School of Life 2017

Designed and typeset by Marcia Mihotich

Printed in Latvia by Livonia Print

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without express prior consent of the publisher.

A proportion of this book has appeared online at

thebookoflife.org

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to make restitution at the earliest opportunity.

The School of Life offers programmes, publications and services to assist modern individuals in their quest to live more engaged and meaningful lives. Weve also developed a collection of content-rich, design-led retail products to promote useful insights and ideas from culture.

www.theschooloflife.com

ISBN 978-1-9997471-6-9

Contents

I

The Nautilus

and Capitalism

Science fiction is one of the most popular but at the same time one of the least prestigious of the literary arts, frequently dismissed as a sub-genre consumed primarily by young males obsessed by the goriest or oddest possibilities for the future of our species.

Yet science fiction is a much-underestimated tool in business; in its utopian (as opposed to dystopian) versions, it invites us to explore imaginatively what we might want the future to be like a little ahead of our practical abilities to mould it as we would wish.

Science fiction may not contain precise answers (how actually to make a jet-pack or a robot that loves us) but it encourages us in something that is logically prior to, and in its own way as important as, technological mastery: the identification of issues we would like to see solved. Changes in society and business seldom begin with actual inventions; they begin with acts of the imagination, with a sharpened sense of a need for something new, be this for an engine, a piece of legislation or a social movement. The details of change may eventually get worked out in laboratories, committee rooms and parliaments, but the crystallisation of the wish for change takes place at a prior stage, in the imaginations of people who know how to envisage what doesnt yet exist.

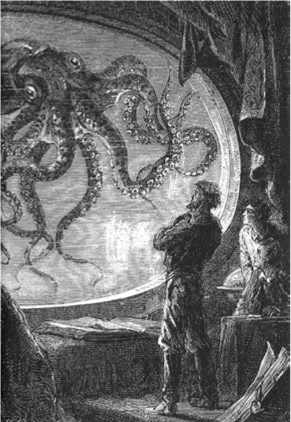

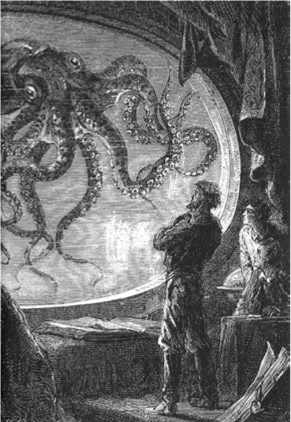

In his novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, published in Paris in 1870, Jules Verne (18281905) narrated the adventures of the Nautilus, a large submarine that tours the worlds oceans often at great depth (the 20,000 leagues about 80,000 kilometres refer to the distance travelled). When writing the story, Verne didnt worry too much about solving every technical issue involved with undersea exploration: he was intent on pinning down capacities he felt it would one day be important to have. He described the Nautilus as being equipped with a huge window even though he had no idea how to make glass that could withstand immense barometric pressures. He imagined the vessel having a machine that could make seawater potable, although the science behind desalination was extremely primitive at the time. And he described the Nautilus as being powered by batteries even though this technology was in its infancy.

Jules Verne was not an enemy of technology. He was deeply fascinated by practical problems. But in writing his novels, he held off from worrying too much about the how questions. He wanted to picture the way things could be, while warding off for a time the many practical objections that would one day have to be addressed. He was thereby able to bring the idea of the submarine into the minds of millions while the technology slowly emerged that would allow the reality to take hold.

Alphonse de Neuville and Edouard Riou, Illustrations for Jules Vernes

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, 1871

Wouldnt glass shatter at that pressure?

Keeping certain questions at bay for long enough to shape a vision.

The key mental move in science fiction what would we want life to be like one day? has traditionally been focused on technology. However, there is no reason why we would not perform equally dramatic thought experiments in other fields, in relation to family life, relationships and, as were about to do here, capitalism.

Asking oneself what a better version of something might be like, without direct tools for a fix to hand, can feel immature and naive. Yet its by formulating visions of the future that we can more clearly start to define what might be wrong with what we have - and set the wheels of change in motion. Through science fiction experiments, we can get into the habit of counteracting detrimental tendencies to inhibit our thinking around wished-for scenarios that seem (in gloomy present moments at least) deeply unlikely. Such experiments are often hugely relevant, because when we look back in history we can see that so many machines, projects and ways of life that once appeared simply utopian have come to pass. Not least Captain Kirks phone.

Captain Kirks communicator from Star Trek, 1966

Sometimes ideas drafted in science fiction pave the way

for real-life developments.

We all have a science fiction side to our brains, which we are normally careful to disguise for fear of humiliation. Yet, as Verne showed us, our visions are what carve out the space in which later developments can occur.

What follows is an attempt to work out aspects of a wiser future for capitalism.

2

Artists and

Supermarket

Tycoons

The Shanghai-based artist Xu Zhen (born 1977) is one of the most celebrated Chinese artists of our age. He operates in a variety of media, including video, sculpture and fine art. His work displays a deep interest in business; he appears at once charmed and horrified by commercial life. In recent years, he has become especially fascinated by supermarkets. Hes interested, in part, in how lovely they can be.

Xu Zhen loves the alluring packaging, the abundance (the feel of lifting something off a shelf and seeing multiple versions of it waiting just behind) and the exquisite precision with which items are displayed. He particularly likes the claim of comprehensiveness that supermarkets implicitly make: the suggestion that they can, within their cavernous interiors, provide us with everything we could possibly need to thrive.

At the same time, Xu Zhen feels that there is something quite wrong with real supermarkets and with commercial life in general. The products sold are rarely the things we genuinely need. Despite the enormous choice, what we require to thrive isnt on offer. Meanwhile, the backstories of the brightly coloured things on sale are often exploitative and dark. Everything has been carefully calculated to get us to spend more than we mean to. Theres cynicism throughout the system.

Next page