Quick-recognition text hierarchy

Read this book in the way that suits you best. Paragraphs are prioritized using different font sizes. The larger the font size the more important the words are to the overall concept or argument.

So, if you only have half an hour to spare, just read the paragraphs set in the two largest font sizes and youll still get a basic overview of the subject.

With an hour at your disposal, get a deeper understanding of the principles and arguments by reading all the paragraphs apart from those in the smallest font size.

If you can set aside a couple of hours, youll be able to read the entire book and get both a well-balanced overview and a detailed comprehension of individual concepts.

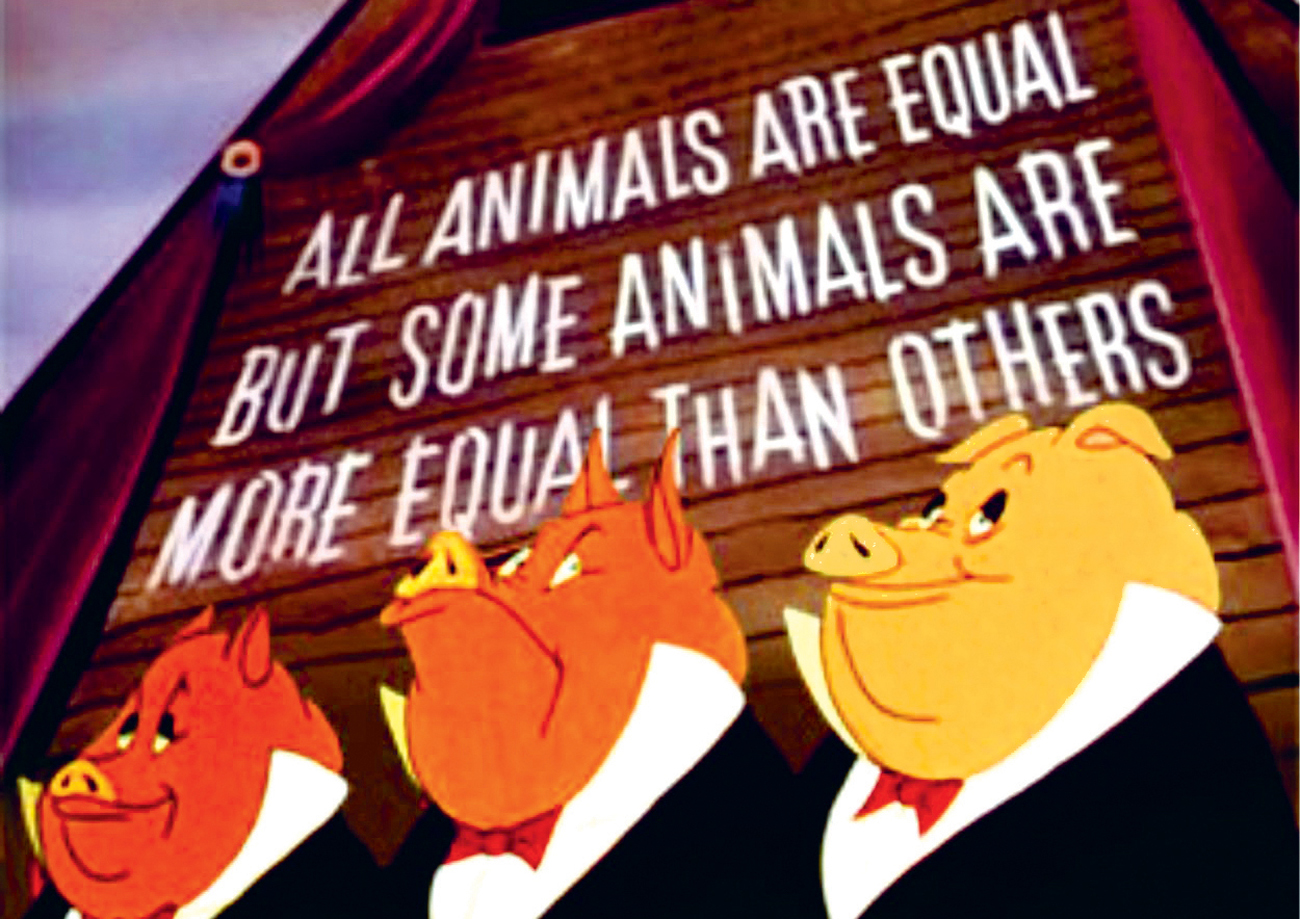

Pertinent and punchy imagery

Images are as much a part of the debate as the text itself. Juxtaposed in a thought-provoking way, or used to expand on the argument, they offer additional insights throughout.

About the Author and Editor

Jacob Field completed his degree in modern history at the University of Oxford, and moved to Newcastle University for his PhD. In 2008 he moved to the University of Cambridge to take up a post-doctoral post at the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure, where he worked on a project examining Britains occupational structure from the 14th to 19th centuries. In 2012 he moved to New Zealand, where he taught economic history at Massey University and the University of Waikato. He has written four popular history books, the latest of which is D-Day In Numbers. An adaptation of his doctoral thesis into a monograph entitled London, Londoners, and the Great Fire of 1666: Disaster and Recovery was published by Routledge in autumn 2017. He is currently a research associate at Cambridge investigating Londons economic history.

Matthew Taylor is Chief Executive of the RSA, a 250-year-old British institution devoted to enriching society through ideas and action to deliver a 21st-century enlightenment. A writer, public speaker and broadcaster, he has written numerous articles on policy, politics, public service reform and cultural theory, and frequently appears on Newsnight, The Daily Politics, and Radio 4s Today and The Moral Maze. He was previously General Secretary and Chief Executive of the Institute for Public Policy Research, Britains leading think tank.

Other titles in the series published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Is Democracy Failing?

Is Gender Fluid?

What Shape Is Space?

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

Contents

Capitalism is an economic system in which the ultimate goal is profit. Goods and services are produced with the aim of making money. Defining capitalism is straightforward, but a more complex question remains: Is it working?

Answering this question requires asking many others: What has capitalism achieved for humanity? Who benefits from the system, and what is the impact if its profits are not shared out equitably? Has capitalism done anything to address social and global inequalities, or has it merely broadened them? Are there any alternatives to capitalism, and what is their efficacy? What have been the environmental consequences of capitalism, and can the system be adapted to deliver a more sustainable future?

Addressing these issues is vital because capitalism is ubiquitous, and has been since it began to emerge in its modern form more than 200 years ago (coinciding with the Industrial Revolution and the beginning of globalization ) and spread across the world to become the dominant economic system. The contemporary world is inextricably linked to capitalism; it is an inescapable force that impacts everyone on the planet and reaches into every aspect of our daily lives. The first chapter of this book details how this happened by charting the evolution of modern capitalism from its roots in late 18th-century Britain all the way to the global financial crisis of 2008. It also explores how the way people thought about economics transformed during this period.

There are competing arguments regarding the success or failure of capitalism.

Ignoring one side or the other leads to a blinkered perspective that negates any possibility of a deeper understanding of how our economy operates. The second and third chapters of this book examine the two sides of the debate. suggests some of the possible solutions that can remedy its most problematic and damaging features.

A One of George Orwells greatest works, Animal Farm (1945) is an allegory for the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the rise of Stalinism. Despite the pigs original promise of equality, they form a dictatorship that is even more oppressive than that of their former human owners.

Industrial Revolution occurs when an economy changes from being mostly agricultural to focus more on manufacturing. It witnesses rapid economic growth and increased productivity.

Globalization is a term used to describe the process of the integration of the world that began to gather pace in the later 19th century. It encompasses economics, culture and politics.

Before delving further, some basic principles about how capitalism operates need to be set out. Firstly, within the capitalist system are economic actors. They may be individuals, companies, institutions or governments. Economic actors are broadly divided into owners and labourers. Owners possess the means of production, which may be natural resources (e. g. land) or capital goods (e.g. tangible assets). All economic actors respond to incentives, chiefly remunerative ones.

Before the 19th century, the majority of owners were individuals; now the most powerful are companies. In a capitalist system, owners tend to be private rather than government bodies. The government-run public sector is focused on services that are supposed to benefit all of society, such as infrastructure, education and health care. The private sector is ultimately based on making money for its owners. Such profit-seeking enterprises are far more diverse in the range of goods and services they provide, which means that in capitalist systems they usually employ more of the workforce and make up more of the economy.

Economic actors produce commodities that are traded through the market, which assigns them a value so exchanges can be made. The earliest markets were barter-based, before money became the primary means of exchange. Money began as physical cash, but this is now being replaced by digital currencies such as bitcoins.