In memory of Robert Coates and Jack McKenna, who are much missed

Copyright David Coates 2000

The right of David Coates to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2000 by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd

Reprinted 2001, 2006

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Coates, David.

Models of capitalism: growth and stagnation in the modern era

/ David Coates.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7456-2058-2

ISBN 0-7456-2059-0 (pbk.)

1. Capitalism. I. Title.

HB501 .C63 2000

330.12'2 dc21

9932965

CIP

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.polity.co.uk

Acknowledgements

with the permission of the publisher, Stanford University Press, 1989 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. The extract from W. Streecks Social Institutions and Economic Performance is reproduced with the permission of Sage Publications. An earlier version of chapter 4 appeared in L. Panitch and C. Leys (eds), The Socialist Register 1999 (Merlin Press); and a fuller version of the Appendix is to be found in New Political Economy, volume 4, number 1.

Preface

By the time a broad comparative study of this kind is completed, whole new sets of debts have necessarily been accumulated: debts to scholars on whose detailed labours the general analysis rests; debts to colleagues who have provided the climate and space in which to read and reflect upon that scholarship; and debts to friends who have read or discussed parts or all of the results of that reading and reflection. The references cited at the end of this volume stand as testimony to the scale of that first debt. Here I would simply like to record my thanks to a smaller group of colleagues and friends.

My understandings of the issues discussed in this volume have benefited enormously from conversations down the years with Leo Panitch, Greg Albo, Peter Nolan and Jeff Henderson. Individual parts of the argument developed here were strengthened by listening to and taking advice from (among others) Andreas Bieler, Phil Cerny, Tony Elger, Diane Elson, Richard Higgott, Colin Leys, Steve Ludlam, David Marsh, Stan Metcalfe, Jamie Peck, Hugo Radice, Gareth Api Richards, Ngai-Ling Sum, Matthew Watson, Rorden Wilkinson and Karel Williams; and the whole manuscript was read (and improved immensely) by Colin Hay, in a characteristic act of generosity and rigour which went far beyond the call of duty. None of them bear any responsibility, of course, for any deficiencies that remain, but each has helped in his or her different way to keep those deficiencies to manageable proportions: and I thank them for that.

Three other sets of acknowledgements are necessary and appropriate. One is to the economic journalists writing for the Financial Times, and in particular to Robert Taylor, for the sheer quality of the reporting on which so many of us now depend. The second is to my former colleagues in the Government Department of the University of Manchester, without whose support and comradeship this whole exercise could never have been completed. And the third, by far the most important, is to both my immediate and my extended family. The writing of this book has been a pleasure because my family have been a pleasure: in the UK most centrally Eileen and Jonathan, but also Edward and Thomas, Anna, Ben, Emma and now Megan, and in the US Mary Jane, Pete and Loran, Mike and Donna, Chris and Carol, Steve and Jo. As Eileen, Jonathan and I now switch locations, from one side of our Atlantic family to the other, it is an appropriate moment to record publicly the extent of my private debt to them all. It is impossible not to believe in the potentiality of the human spirit when surrounded by a family of such quality and love.

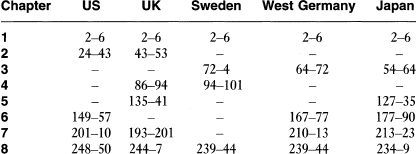

Guide to Country Story Lines

The following table indicates the main blocks of material on particular countries.

1

Capitalist Models and Economic Growth

Amid the optimism of a new century, the legacies of the past still lie like a nightmare on the brain of the living. Communism may have fallen (in Europe at least) but in the policy-making circles of the advanced capitalist world three quite enormous issues of economic policy remain to be resolved. In a capitalist economy, is the achievement of economic growth best left to the market, or should its orchestration be a central task of government? Do old ways of governing capitalist economies need now to be replaced by new ones? And should we be in pursuit of the one right way of ordering economic and social life in the pursuit of economic growth, or do we still face a range of viable capitalist models?

These questions have all been around for a very long time, but they have gathered new urgency and force of late, as the pattern of economic performance among advanced capitalist economies has altered sharply. In the 1980s, in both the US and the UK, the policy debate was dominated by questions of economic decline, power was held by advocates of market-based capitalism, and the majority of their critics were pressing strongly for a managed economy of the seemingly more successful German or Japanese variety. By the late 1990s, in contrast, it was the German and Japanese economies that were widely perceived to be in difficulties, governmental power in both Washington and London had been captured by centre-left parties, and it was the advocates of unregulated capitalism who now offered sceptical opposition to the new third way in politics. Suddenly, in the context of increasing globalization, old certainties have been replaced by new doubts; and the search is on again for solutions to problems of economic growth which, only a decade ago, appeared to have clear, definite, but varied solutions. In the face of such uncertainties, students of contemporary politics need rapidly to familiarize themselves with things hitherto of concern only to academic specialists: the causes of the various postwar economic miracles, the meaning and significance of globalization, the virtues and vices of flexible labour markets, the difference between first, second and third ways in economic management, the nature of different capitalist models, and so on. The purpose of this volume is to facilitate that process of rapid learning.