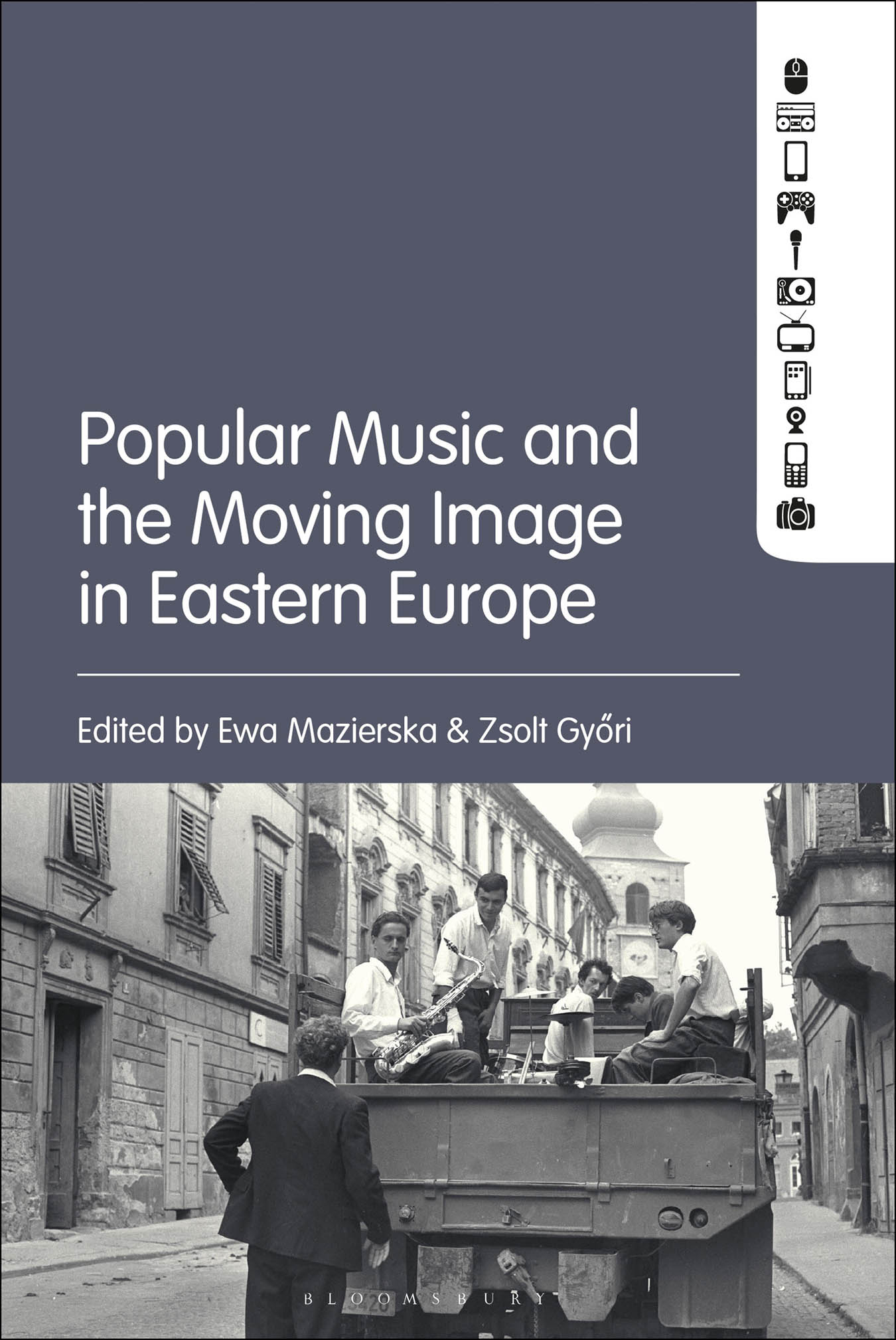

Popular Music and the Moving Image in Eastern Europe

Contents

Ewa Mazierska and Zsolt Gyri

Music is the most pervasive element of film (and other forms of moving image) and the two mediums share a long history of artistic affinities (Inglis 2003, 1), but it is also its most invisible element. According to popular description, film is a visual medium. Much more rarely do we encounter claims of it being an aural medium, despite the fact that even silent films were shown to the accompaniment of music. Yet, while in the West the aural dimension and especially music eventually received their due recognition with regard to musicals, biopics, music videos and music documentaries, as well as film music (for example, Frith, Goodwin and Grossberg 1993; Romney and Wootton 1995; Mundy 1999; Robertson Wojcik and Knight 2001; Dyer 2002; Inglis 2003; Vernallis 2004; Edgar, Fairclough-Isaacs and Halligan 2013), in scholarship on Eastern European cinema this topic remains neglected, especially if we exclude Russia from Eastern Europe, which is the case here.

Such neglect can be explained by several factors. The most important of them is an auteurist bias in Eastern European film studies and to some extent popular music studies. Until recently, the vast majority of books about Eastern European cinema, written in local languages and even more so in English, were concerned with the countries leading directors, during state socialism, whose work was treated as conveying their unique vision, typically at odds with the Party ideologies. In this way directors such as Andrzej However, the situation of Eastern European musicals was allegedly more perilous than that of their Western counterparts, due to the film industry in this region lacking the financial and technological resources, as well as tradition, to produce spectacles enticing eyes and ears (on this argument in relation to Polish cinema see Michaek 1981, 15558). These perspectives, in our opinion, are short-sighted and often fail to recognise the significance which auteur directors ascribed to music in their films on the one hand and to the cult popularity music cinema enjoyed, on the other hand. This collection is meant to challenge them by focusing on types of screen products, in which music draws attention to itself, as is the case, most obviously, with musicals and music videos, but also with music documentaries, and some experimental and fiction films, for example those casting rock and pop stars in main roles. We limit ourselves to the relationship between the moving image and popular music because such music is usually contemporaneous with film, hence the relationship between music and film on such occasions is more intimate and culturally more specific, as noticed by Rick Altman, who wrote: While classical music is particularly able to provide routine commentary and to evoke generalized emotional reactions, popular song is often capable of serving a more specific narrational purpose (Altman 2001, 26). By focusing on the interface between popular music and the moving image, this collection fills a significant gap in the scholarship in two fields: Eastern European cinema and music in film. It also endeavours to paint a less biased image of Eastern European cinema as made up by a handful of masterpieces created by rebellious auteurs.

Although it is beyond the scope of this volume to present the history of popular music on Eastern European screens, especially given that Eastern Europe is not a homogenous whole but a collection of diverse regions and countries, we would like to sketch here a chronology of developments, which led to music gaining in importance. Before we do so, however, lets look briefly at the main types of relationship between popular music and the moving image, identified by scholars focusing on Western cinema.

Illustration, beautification, documentation and synaesthesia

From a historical perspective it is possible to identify four main types of relationship between music and the moving image. In the first type music simply illustrates what we see on screen and fills gaps in the narrative. Such a role of music prevails in most films, including silent cinema. When we talk about film music, typically we have in mind this function of music. The second one is to beautify represented reality or, more broadly, to transform it. This function of music is predominant in musicals. The vast majority of musicals belong to spectacular and non-realistic cinema with narrative function being subordinate to that of creating breath-taking performance (Mundy 1999, 226). In musicals the world tends to be brighter, more colourful than in reality, people are more successful and happier, and live in harmony with each other. In the relationship of the third type, moving image is used to document music as music or a social phenomenon. Such a relationship can be observed in music documentaries, most conspicuously in rock concert films (Edgar, Fairclough-Isaacs and Halligan 2013), but also in fiction films which employ rock stars or take issue with the lives of musicians and music subcultures, and in many music videos. The fourth relationship can be summarized as synaesthesia, namely an artwork, in which music and film reflect affinities between them, be it sensual, technical, metaphysical or referring to specific aspects of their meanings (Cook 1998, 2456). Such an approach is taken in many music videos, particularly those for electronic music (Cameron 2013) and experimental films, but also, in some cases, in auteurist fictional films, for example in the productions of Derek Jarman. Of course, these types of relationship are ideal models. In reality, these specific functions and relationships overlap.

If we map the fourfold classification of the music-image synergy onto the history of the moving image, then we notice that with the passage of time music in films gains more importance and autonomy. This reflects the growing commercial power of popular music, especially pop-rock, which since the 1960s has dominated the soundtrack of American and European films. In relation to Western media, John Mundy uses the term commercial synergy. Such synergy was reflected, for example, in a frequent practice in the 1980s and 1990s of releasing the soundtrack of a film on CD together with releasing the film on DVD by companies which specialized in both film and music production, such as Time-Warner and Sony (Mundy 1999, 22729; see also Smith 1998; Knight and Robertson Wojcik 2001: 23).

Admittedly, under state socialism commercial synergy played a smaller role than in the West and especially Hollywood due to its cinema being less market-oriented. However, we observe there the same trend, namely a shift from music being used to illustrate action, through beautification, to image serving to document music and finally, to synaesthesia. In the first decade or so after the end of the Second World War music in films was typically inconspicuous. Beautification of reality through popular music was the main strategy used during the period of socialist realism. Documentation dominated in the 1960s and 1970s, when rock started to be seen as a distinct music genre and an important social phenomenon. Finally, synaesthesia pertains to the 1980s and later decades, when video entered the scene and developed as a specific genre. During this period we can also find examples of synaesthesia in fiction films, for example in Stntang (Satantango, 1994) by Bla Tarr. Lets now address these developments in greater detail.

Next page