Eo Wilson - Biophilia

Here you can read online Eo Wilson - Biophilia full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1990, publisher: Harvard University Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

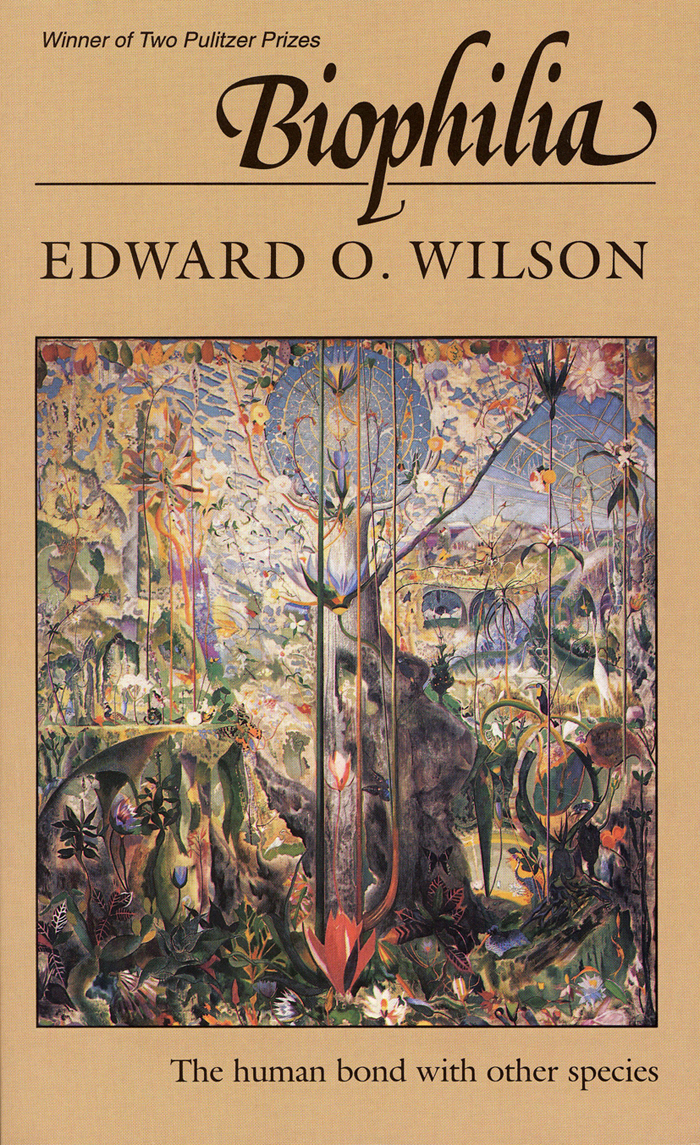

- Book:Biophilia

- Author:

- Publisher:Harvard University Press

- Genre:

- Year:1990

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Biophilia: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Biophilia" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Biophilia — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Biophilia" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

BIOPHILIA

Soft, to your places, animals, Your legendary duty calls.

THOMAS KINSELLA

EDWARD O. WILSON

Harvard University Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

Copyright 1984 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Marianne Perlak

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Wilson, Edward Osborne, 1929

Biophilia.

Bibliography: p.

1. Nature conservation. 2. BiologyPhilosophy. I. Title.

QH75.W534 1984 333.9516 84-9052

ISBN 0-674-07441-6 (cloth)

ISBN 0-674-07442-4 (paper)

O N MARCH 12, 1961, I stood in the Arawak village of Bernhardsdorp and looked south across the white-sand coastal forest of Surinam. For reasons that were to take me twenty years to understand, that moment was fixed with uncommon urgency in my memory. The emotions I felt were to grow more poignant at each remembrance, and in the end they changed into rational conjectures about matters that had only a distant bearing on the original event.

The object of the reflection can be summarized by a single word, biophilia, which I will be so bold as to define as the innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes. Let me explain it very briefly here and then develop the larger theme as I go along.

From infancy we concentrate happily on ourselves and other organisms. We learn to distinguish life from the inanimate and move toward it like moths to a porch light. Novelty and diversity are particularly esteemed; the mere mention of the word extraterrestrial evokes reveries about still unexplored life, displacing the old and once potent exotic that drew earlier generations to remote islands and jungled interiors. That much is immediately clear, but a great deal more needs to be added. I will make the case that to explore and affiliate with life is a deep and complicated process in mental development. To an extent still undervalued in philosophy and religion, our existence depends on this propensity, our spirit is woven from it, hope rises on its currents.

There is more. Modern biology has produced a genuinely new way of looking at the world that is incidentally congenial to the inner direction of biophilia. In other words, instinct is in this rare instance aligned with reason. The conclusion I draw is optimistic: to the degree that we come to understand other organisms, we will place a greater value on them, and on ourselves.

A T BERNHARDSDORP on an otherwise ordinary tropical morning, the sunlight bore down harshly, the air was still and humid, and life appeared withdrawn and waiting. A single thunder-head lay on the horizon, its immense anvil shape diminished by distance, an intimation of the rainy season still two or three weeks away. A footpath tunneled through the trees and lianas, pointing toward the Saramacca River and far beyond, to the Orinoco and Amazon basins. The woodland around the village struggled up from the crystalline sands of the Zanderij formation. It was a miniature archipelago of glades and creekside forest enclosed by savanna grassland with scattered trees and high bushes. To the south it expanded to become a continuous lacework fragmenting the savanna and transforming it in turn into an archipelago. Then, as if conjured upward by some unseen force, the woodland rose by stages into the triple-canopied rain forest, the principal habitat of South Americas awesome ecological heartland.

In the village a woman walked slowly around an iron cooking pot, stirring the fire beneath with a soot-blackened machete. Plump and barefoot, about thirty years old, she wore two long pigtails and a new cotton dress in a rose floral print. From politeness, or perhaps just shyness, she gave no outward sign of recognition. I was an apparition, out of place and irrelevant, about to pass on down the footpath and out of her circle of required attention. At her feet a small child traced meanders in the dirt with a stick. The village around them was a cluster of no more than ten one-room dwellings. The walls were made of palm leaves woven into a herringbone pattern in which dark bolts zigzagged upward and to the onlookers right across flesh-colored squares. The design was the sole indigenous artifact on display. Bernhardsdorp was too close to Paramaribo, Surinams capital, with its flood of cheap manufactured products to keep the look of a real Arawak village. In culture as in name, it had yielded to the colonial Dutch.

A tame peccary watched me with beady concentration from beneath the shadowed eaves of a house. With my own, taxonomists eye I registered the defining traits of the collared species, Dicotyles tajacu: head too large for the piglike body, fur coarse and brindled, neck circled by a pale thin stripe, snout tapered, ears erect, tail reduced to a nub. Poised on stiff little dancers legs, the young male seemed perpetually fierce and ready to charge yet frozen in place, like the metal boar on an ancient Gallic standard.

A note: Pigs, and presumably their close relatives the peccaries, are among the most intelligent of animals. Some biologists believe them to be brighter than dogs, roughly the rivals of elephants and porpoises. They form herds of ten to twenty members, restlessly patrolling territories of about a square mile. In certain ways they behave more like wolves and dogs than social ungulates. They recognize one another as individuals, sleep with their fur touching, and bark back and forth when on the move. The adults are organized into dominance orders in which the females are ascendant over males, the reverse of the usual mammalian arrangement. They attack in groups if cornered, their scapular fur bristling outward like porcupine quills, and can slash to the bone with sharp canine teeth. Yet individuals are easily tamed if captured as infants and their repertory stunted by the impoverishing constraints of human care.

So I felt uneasyperhaps the word is embarrassed in the presence of a captive individual. This young adult was a perfect anatomical specimen with only the rudiments of social behavior. But he was much more: a powerful presence, programed at birth to respond through learning steps in exactly the collared-peccary way and no other to the immemorial environment from which he had been stolen, now a mute speaker trapped inside the unnatural clearing, like a messenger to me from an unexplored world.

I stayed in the village only a few minutes. I had come to study ants and other social insects living in Surinam. No trivial task: over a hundred species of ants and termites are found within a square mile of average South American tropical forest. When all the animals in a randomly selected patch of woodland are collected together and weighed, from tapirs and parrots down to the smallest insects and roundworms, one third of the weight is found to consist of ants and termites. If you close your eyes and lay your hand on a tree trunk almost anywhere in the tropics until you feel something touch it, more times than not the crawler will be an ant. Kick open a rotting log and termites pour out. Drop a crumb of bread on the ground and within minutes ants of one kind or another drag it down a nest hole. Foraging ants are the chief predators of insects and other small animals in the tropical forest, and termites are the key animal decomposers of wood. Between them they form the conduit for a large part of the energy flowing through the forest. Sunlight to leaf to caterpillar to ant to anteater to jaguar to maggot to humus to termite to dissipated heat: such are the links that compose the great energy network around Surinams villages.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Biophilia»

Look at similar books to Biophilia. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Biophilia and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.