A LSO BY E DWARD O. W ILSON

Letters to a Young Scientist (2013)

The Leafcutter Ants: Civilization by Instinct, with Bert Hlldobler (2011)

Kingdom of Ants: Jos Celestino Mutis and the Dawn of Natural History in the New World,

with Jos M. Gmez Durn (2010)

Anthill: A Novel (2010)

The Superorganism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies, with Bert Hlldobler (2009)

The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth (2006)

Nature Revealed: Selected Writings, 19492006 (2006)

From So Simple a Beginning: The Four Great Books of Darwin,

edited with introductions (2005)

Pheidole in the New World: A Dominant, Hyperdiverse Ant Genus (2003)

The Future of Life (2002)

Biological Diversity: The Oldest Human Heritage (1999)

Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (1998)

In Search of Nature (1996)

Journey to the Ants: A Story of Scientific Exploration,

with Bert Hlldobler (1994)

Naturalist (1994);

new edition, 2006

The Diversity of Life (1992)

The Ants,

with Bert Hlldobler (1990); Pulitzer Prize, General Nonfiction, 1991

Success and Dominance in Ecosystems: The Case of the Social Insects (1990)

Biophilia (1984)

Promethean Fire: Reflections on the Origin of the Mind ,

with Charles J. Lumsden (1983)

Genes, Mind, and Culture: The Coevolutionary Process,

with Charles J. Lumsden (1981)

On Human Nature (1978);

Pulitzer Prize, General Nonfiction, 1979

Caste and Ecology in the Social Insects,

with George F. Oster (1978)

Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975);

new edition, 2000

A Primer of Population Biology,

with William H. Bossert (1971)

The Insect Societies (1971)

The Theory of Island Biogeography,

with Robert MacArthur (1967)

C ONTENTS

C ONTENTS

P ROLOGUE

P ROLOGUE

T HERE IS NO GRAIL more elusive or precious in the life of the mind than the key to understanding the human condition. It has always been the custom of those who seek it to explore the labyrinth of myth: for religion, the myths of creation and the dreams of prophets; for philosophers, the insights of introspection and reasoning based upon them; for the creative arts, statements based upon a play of the senses.

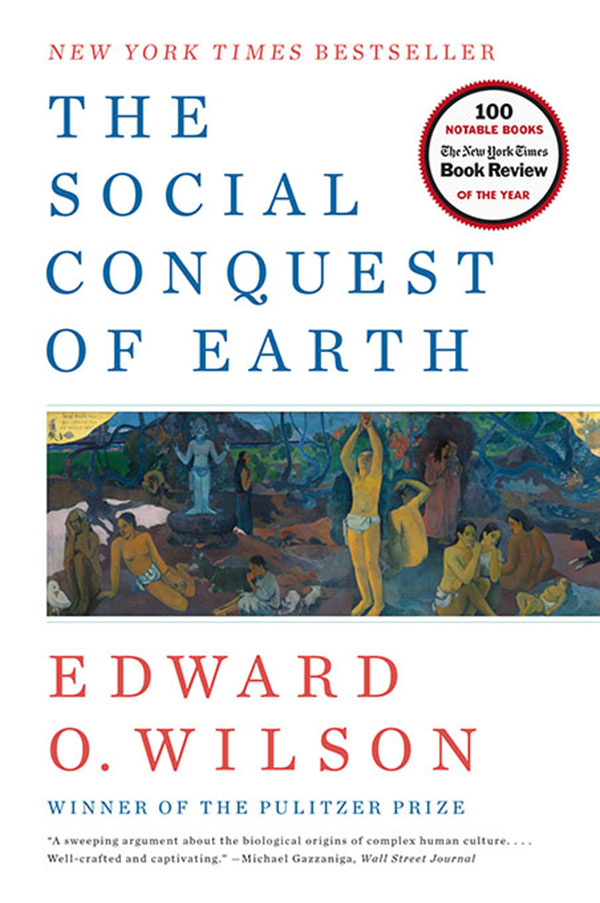

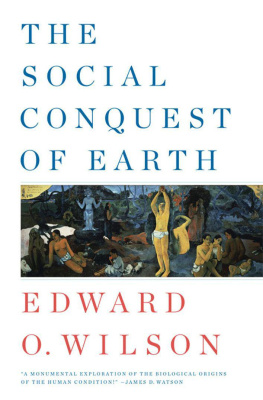

Great visual art in particular is the expression of a persons journey, an evocation of feeling that cannot be put into words. Perhaps in the hitherto hidden lies deeper, more essential meaning. Paul Gauguin, hunter of secrets and famed Maker of Myths (as he has been called), made this attempt. His story is a worthy backdrop for the modern answer to be offered in the present work.

Late in 1897, at Punaauia, three miles from the Tahitian port of Papeete, Gauguin sat down to put on canvas his largest and most important painting. He was weak from syphilis and a series of debilitating heart attacks. His funds were nearly gone, and he was depressed by the news that his daughter Aline had recently died of pneumonia in France.

Gauguin knew his time was running out. He meant this painting to be his last. And so when he finished, he went into the mountains behind Papeete to commit suicide. He carried with him a vial of arsenic he had stored, perhaps unaware of how painful death by this poison can be. He intended to hide himself before he took it, so that his corpse would not be found right away and instead would be eaten by ants.

But then he relented, and returned to Punaauia. Although there was very little left to his life, he had decided to soldier on. To survive, he took a six-franc-a-day job in Papeete as a clerk in the Office of Public Works and Surveys. In 1901, he sought even greater isolation, moving to the little island of Hiva Oa in the faraway Marquesas archipelago. Two years later, while embroiled in legal problems, Paul Gauguin died of syphilitic heart failure. He was buried in the Catholic cemetery on Hiva Oa.

I am a savage, he wrote a magistrate a few days before the end. And civilized people suspect this, for in my works there is nothing so surprising and baffling as this savage in spite of myself aspect.

Gauguin had come to French Polynesia, to this almost impossible end of the world (only Pitcairn and Easter Island are more remote), to find both peace and a new frontier of artistic expression. He attained the second, if not the first.

Gauguins journey of body and mind was unique among major artists of his era. Born in Paris in 1848, he was raised in Lima and then Orlans by his half-Peruvian mother. This ethnic mix gave a hint of what was to come. As a young man he joined the French merchant marines and traveled around the world for six years. During this period, in 187071, he saw action in the Franco-Prussian War, in the Mediterranean and North Sea. Back in Paris he at first gave little thought to art, instead becoming a stockbroker under the guidance of his wealthy guardian Gustave Arosa. His interest in art was sparked and sustained by Arosa, a major collector of French art, including the latest works of impressionism. When the French stock market crashed in January 1882 and his own bank failed, Gauguin turned to painting and began to develop his considerable talent. Nurtured in impressionism by painters of undoubted greatnessPissarro, Czanne, Van Gogh, Manet, Seurat, Degashe strove to join their ranks. As he traveled about, from Pontoise to Rouen, from Pont-Aven to Paris, he created portraits, still lifes, landscapes, in work increasingly phantasmagoric, portending the Gauguin who was to emerge.

But Gauguin was disappointed with the result, and lingered only a short time in the company of his dazzling contemporaries. He had not grown rich and famous with his own efforts, even though, as he later declared, he knew he was a great artist. He longed for a simpler, easier life to meet this destiny. Paris, he wrote in 1886, is a wasteland for a poor man.... I am going to Panama to live the life of a native.... I shall take my paints and brushes and reinvigorate myself far from the company of men.

It was not just poverty that drove Gauguin from civilization. He was at heart a restless soul, an adventurer, ever anxious to find what lay beyond the place he lived. In art, he was accordingly an experimentalist. In his wanderings he was drawn to the exoticism of non-Western cultures, and wanted to immerse himself in them in search of new modes of visual expression. He spent time in Panama and then Martinique. Returning home, he applied for a position in the French-ruled province of Tonkin, now northern Vietnam. When that failed, he turned at last to French Polynesia, the ultimate paradise.

On June 9, 1891, Gauguin arrived at Papeete and immersed himself in the indigenous culture. In time he became an advocate of native rights, and therefore a troublemaker in the eyes of the colonial authorities. Of vastly greater importance, he pioneered the new style called primitivism: flat, pastoral, often violently colorful, simple and direct, and authentic.

Next page

C ONTENTS

C ONTENTS

P ROLOGUE

P ROLOGUE