Table of Contents

Postcolonial Theory

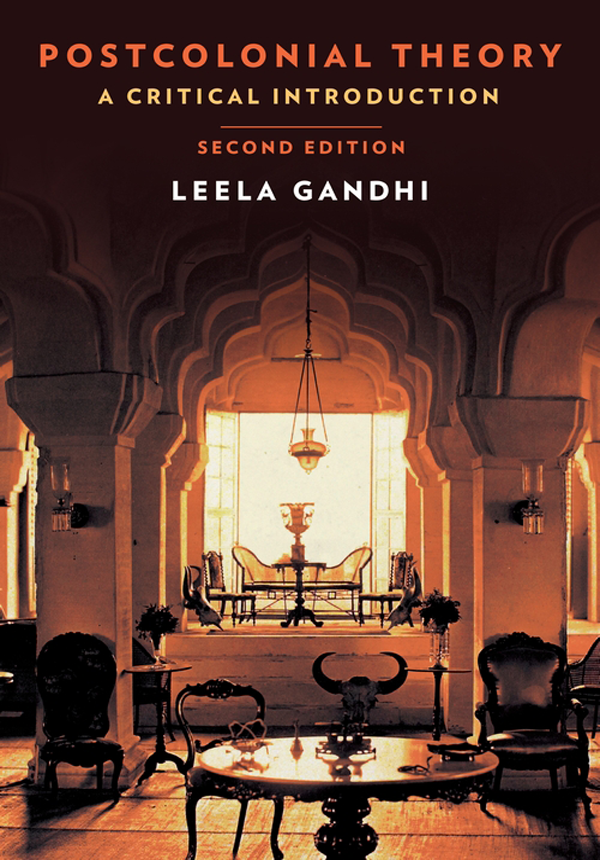

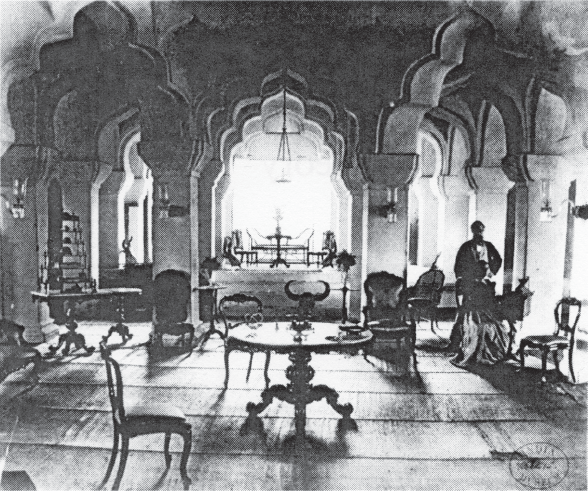

Interior of Tuncum, Madurai by Edmund David Lyon, Prints and Drawings Section of the Oriental and India Office Collections, British Library (OIOC photo 1001 [2975])

Postcolonial Theory

A Critical Introduction

Second Edition

Leela Gandhi

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54856-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gandhi, Leela, 1966-

Title: Postcolonial theory: a critical introduction / Leela Gandhi.

Description: Second Edition. | New York: Columbia University Press, [2018] | Previous edition: 1998. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018032553 (print) | LCCN 2018034095 (e-book) | ISBN 9780231548564 (e-book) | ISBN 9780231178389 (cloth: acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780231178396 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Postcolonialism.

Classification: LCC JV51 (e-book) | LCC JV51 .G36 2018 (print) | DDC 325/.301dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018032553

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Elliott S. Cairns

Cover image: Madura. The interior of the Tuncum. Photograph by Edmund David Lyon, c. 1868. British Library, London, UK / British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Images.

Contents

F or the first edition of this book, I thank my former colleagues at La Trobe University and Elizabeth Weiss at Allen & Unwin. Thanks also to Marion Campbell, Dipesh Chakrabarty, Joanne Finkelstein, David Lloyd, Rajyashree Pandey, Sanjay Seth, and Ruth Vanita. Pauline Nestor and Bronte Adams gave much support and read through the initial manuscript with care and patience.

For the second edition, I am grateful to my colleagues and students at Brown University for institutional support and for conversations that have enriched my understanding of postcolonial thinking. I thank Philip Leventhal and the editorial team at Columbia University Press for the opportunity to revisit the material of this book, as well as the two anonymous readers of this edition for their generous and generative suggestions.

I presented versions of the new material in lectures at Ohio State University, Dartmouth College, Stanford University, the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in Delhi, and the University of Oxford. I learned much from audience feedback on these occasions. I am full of gratitude to Tamara Chin, who has been a crucial interlocutor and mainstay.

I n the late 1990s, when I began work on the first edition of this book, postcolonial theory was the domain of a handful of thinkers. It was very much an emergent field, in Raymond Williamss sense of emergent, meaning something that is starting to stand apart from the status quo while being absorbed in the current. Early postcolonialism exposed the limits of academic Eurocentrism, but it did so as an adjunct to mainstream critical theory. It had a distinct humanistic idiom and methodologymore value based than positivist, though always with materialist deference to real events, people, places, pasts, and so on. Most practicing critics at the time came out of literature departments (predominantly comparative and Anglophone) and from conceptual branches of history and historiography. They used their considerable skills to speak in speculative rather than practical terms about the contemporary non-West. Finally, postcolonialism was party toindeed, at the helm ofa new philosophical skepticism in some European and American scholarly systems, with offshoots in counterpart postcolonial settings. This last claim needs elaboration.

Traditionally, skeptical systems maintain that we can never reliably know the external world and other minds due to the conditional nature of apperception, in essence. The latter-day variant to which I refer is taken up with representations of power relations that influence the way we think, more than the problem of knowledge in the abstract. It proposes that axiomatic forms of institutional knowledgeand this covers a multitude of sinsare especially untrustworthy as they mask the petty instrumental designs of one or other vested interest. This turns skepticism into a kind of conscientious doubt about universal truth-claims and also into a hermeneutics of suspicion, to invoke a term coined by Paul Ricoeur that has gained traction in literary and cultural studies. In this guise, skepticism shares crucial properties with critique. Yet, there is a distinction.

Michel Foucault once described critique as the disposition to question governing values from the perspective of the present. The purpose, he hinted, is not to reject power and the mode of truth, tout court, but rather to put a limit on these by making them contingentthat is, answerable to the needs of this or that moment and, therefore, always dynamic. Critique may not know the outcomes it wants in advance, but it is, nonetheless, in pursuit of a more truthful truth, if we follow Foucault. Skepticism suspends this desire, or forgets it for a while in the space-clearing exercise of incredulity. This does not mean that skeptical systems lack conviction, merely that these are inextricable from a logic of uncertainty. They are experiential rather than epistemological, pluralistic rather than foundational, and above all, they are relationalthat is, open to the vagaries of encounter.

Such a mood of incredulity was rife in the milieu of early postcolonial theory. It grew out of contemporary poststructuralism and postmodernism, mainly, and was directed, variously, against grand narratives, the figures of the subject and of identity, disciplinary objects such as literature, text, history, archive, philosophy, canons of all description, nationalisms (both colonial and postcolonial), class (as the only unit of collective action), reason and rationality, progress and modernity, gender, and the human, to name a few. There were quarrels along the way on behalf of hard-won belief systems. Marxist critics, and stakeholders in the considerable merits of anticolonial liberation movements, queried the absence of an oppositional or alternative world view in the new dispensation. Traditionalists held the ground for existing forms of culture and coherence. Many of these quarrels are documented in the first edition of Postcolonial Theory.

Some twenty years since, I want to ask if the radical skepticism of early postcolonialism has passed over into something more like critique, in Foucaults sense, without loss of the best part of its formative iconoclasm. Can we point to an incipient belief system, or even a set of provisional ameliorative practices (albeit relational and pluralistic) in the field? And, if so, what are the conditions that have helped these come into view?