Chion Michel. - Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen

Here you can read online Chion Michel. - Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Lightning Source Inc. (Tier 3), genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

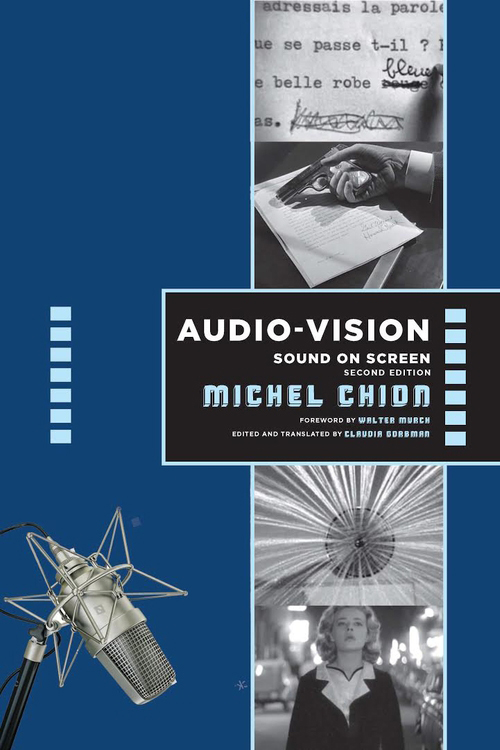

- Book:Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen

- Author:

- Publisher:Lightning Source Inc. (Tier 3)

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

AUDIO-VISION

AUDIO-VISION

SOUND ON SCREEN

SECOND EDITION

MICHEL CHION

FOREWORD BY WALTER MURCH

EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY CLAUDIA GORBMAN

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Originally published in France as:

Laudio-vision. Son et image au cinma, Fourth Edition By Michel CHION

2017, Armand Colin, Malakoff for the current edition

2005, 2013, Armand Colin, Paris

1990 Editions Nathan, Paris

ARMAND COLIN is a trademark of DUNOD Editeur - 11, rue Paul Bert - 92240 MALAKOFF.

Second English edition 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54637-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Chion, Michel, 1947 author. | Gorbman, Claudia, editor, translator.

Title: Audio-vision : sound on screen / Michel Chion ; edited and translated by Claudia Gorbman.

Other titles: Audio-vision. English

Description: Second edition. | New York : Columbia University Press, [2018] | Translation of: Laudio-vision : son et image au cinema. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018034529 (print) | LCCN 2018043470 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231185882 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231185899 (paperback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Sound motion pictures. | Motion picturesSound effects. | Motion picturesAesthetics.

Classification: LCC PN1995.7 (ebook) | LCC PN1995.7 .C4717 2018 (print) | DDC 791.4302/4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018034529

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover image: microphone: Shutterstock

CONTENTS

We gestate in Sound, and are born into Sight

Cinema gestated in Sight, and was born into Sound.

W e begin to hear before we are born, four and a half months after conception. From then on, we develop in a continuous and luxurious bath of sounds: the song of our mothers voice, the swash of her breathing, the trumpeting of her intestines, the timpani of her heart. Throughout the second four-and-a-half months, Sound rules as solitary Queen of our senses: the close and liquid world of uterine darkness makes Sight and Smell impossible, Taste monochromatic, and Touch a dim and generalized hint of what is to come.

Birth brings with it the sudden and simultaneous ignition of the other four senses, and an intense competition for the throne that Sound had claimed as hers. The most notable pretender is the darting and insistent Sight, who dubs himself King as if the throne had been standing vacant, waiting for him.

Ever discreet, Sound pulls a veil of oblivion across her reign and withdraws into the shadows, keeping a watchful eye on the braggart Sight. If she gives up her throne, it is doubtful that she gives up her crown.

In a mechanistic reversal of this biological sequence, Cinema spent its youth (18921927) wandering in a mirrored hall of voiceless images, a thirty-five year bachelorhood over which Sight ruled as self-satisfied, solipsistic Kingnever suspecting that destiny was preparing an arranged marriage with the Queen he thought he had deposed at birth.

This cinematic inversion of the natural order may be one of the reasons that the analysis of sound in films has always been peculiarly elusive and problematical, if it was attempted at all. In fact, despite her dramatic entrance in 1927, Queen Sound has glided around the hall mostly ignored even as she has served us up her delights, while we continue to applaud King Sight on his throne. If we do notice her consciously, it is often only because of some problem or defect.

Such self-effacement seems at first paradoxical, given the power of sound and the undeniable technical progress it has made in the last sixty-five years. A further examination of the source of this power, however, reveals it to come in large part from the very handmaidenly quality of self-effacement itself: by means of some mysterious perceptual alchemy, whatever virtues sound brings to the film are largely perceived and appreciated by the audience in visual termsthe better the sound, the better the image. The French composer, filmmaker, and theoretician Michel Chion has dedicated a large part of and this alchemy also lies at the heart of his three earlier, as-yet-untranslated works on film sound: Le Son au cinma , La Voix au cinma , and La Toile troue. It gives me great pleasure to be able to introduce this author to the American public, and I hope it will not be long before his other works are also translated and published.

It is symptomatic of the elusive and shadowy nature of film sound that Chions four books stand relatively alone in the landscape of film criticism, representing as they do a significant portion of everything that has ever been published about film sound from a theoretical point of view. For it is also part of Sounds effacement that she respectfully declines to be interviewed, and previous writers on film have with uncharacteristic circumspection largely respected her wishes.

It is also characteristic that this silence has been broken by a European rather than an Americaneven though sound for films was an American invention, and nearly all of the subsequent developments (including the most recent Dolby SR-D digital soundtrack) have been American or Anglo-American. As fish are the last to become aware of the water in which they swim, Americans take their sound for granted. But such wasand isnot the case in Europe, where the invasion of sound from across the Atlantic in 1927 was decidedly a mixed blessing and something of a curse: not without reason is of Audio-Vision (on the arrival of sound) ironically subheaded Sixty Years of Regrets.

There are several reasons for Europes ambivalent reaction to film sound, but the heart of the problem was foreshadowed by Faust in 1832, when Goethe had him proclaim:

It is written that in the Beginning was the Word!

Hmm already I am having problems.

The early sound films were preeminently talking films, and the Wordwith all of the power that language has to divide nation from nation as well as conquer individual heartshas long been both the Achilles heel of Europe as well as its crowning glory. In 1927 there were over twenty different languages spoken in Europe by two hundred million people in twenty-five different, highly developed countries. Not to mention different dialects and accents within each language and a number of countries such as Switzerland and Belgium that are multilingual.

Silent films, however, which blossomed during and after the First World War, were Edenically oblivious of the divisive powers of the Word, and were thus ablewhen they so desiredto speak to Europe as a whole. It is true that most of these films had intertitle cards, but these were easily and routinely switched according to the language of the country in which the film was being shown.

Even so, title cards were generally discounted as a necessary evil and there were some films, like those of writer Carl Mayer ( The Last Laugh ) , that managed to tell their story without any cards at all and were highly esteemed for this ability, which was seen as the wave of the future.

It is also worth recalling that at that time the largest studio in Europe was Nordisk Films in Denmark, a country whose population of two million souls spoke a language understood nowhere else. And Asta Nielsen, the Danish star who made many films for Ufa Studios in Germany, was beloved equally by French and German soldiers during the 191418 warher picture decorated the trenches on both sides. It is doubtful that the French poet Apollinaire, if he had heard her speaking in German, would have written his ode to her

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen»

Look at similar books to Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.