BLOOD AND BRONZE

PADDY DOCHERTY

Blood and Bronze

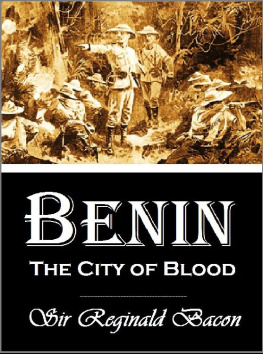

The British Empire and the Sack of Benin

HURST & COMPANY, LONDON

First published in the United Kingdom in 2021 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

New Wing, Somerset House, Strand, London, WC2R 1LA

Paddy Docherty, 2021

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United Kingdom

The right of Paddy Docherty to be identified as the author of this publication is asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Distributed in the United States, Canada and Latin America by Oxford University Press, 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book

is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781787384569

This book is printed using paper from registered sustainable and managed sources.

www.hurstpublishers.com

This book is dedicated to Ekang,

a victim of the British Empire

who never received justice

CONTENTS

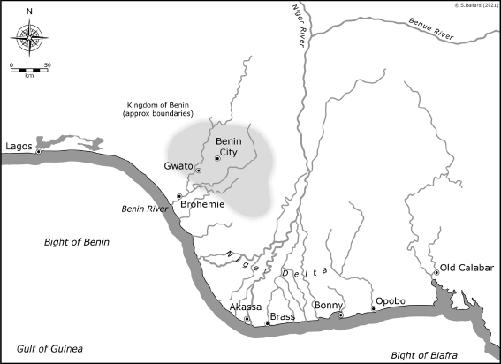

Niger Delta region in the late nineteenth century

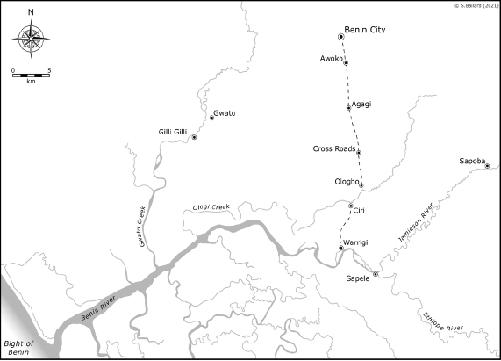

Advance of the Benin Punitive Expedition, February 1897

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to the staff of the National Archives in Kew, and to Ruth Loughrey and Scarlett Dennett at Unilever Art, Archives and Record Management in Port Sunlight. Particular thanks go to Jerry Rudman, archivist at Uppingham School, for his generous help with material on James Phillips. I am also grateful to Anne Jones at Companies House archives, Katie Barrett at the Cheltenham College archive, the archivists at Liverpool Record Office, and Sam Sales at Special Collections in the Bodleian Library.

My gratitude goes to the Society of Authors for their support during the writing of this book. Thanks to Charles Walker at United Agents, Michael Dwyer at Hurst Publishers, and Farhaana Arefin for her dedicated editing. Posthumous thanks to my late father, Robert Docherty, who drew the illustrations for this book in the last year of his life. Aita Ighodaro deserves an honourable mention for accompanying me on that visit to the British Museum, and I thank Olly Hyde-Smith, Julia Popescu, and Kate & Gunnar. Special thanks go to Markta Mojov.

This book began life as an effort to tell the full story of one episode of colonial wrongdoing; it was researched and written with a growing sense of horror and shame as I learnt more about the extraordinary violence of the British Empire in what is now Nigeria. The vast majority of the victims died anonymously and uncounted, but we are able to put a name to Ekang, the woman who suffered one of the most shocking colonial crimes that I uncovered in the archives. She stands in for all those harmed by the British Empire with no hope of justice, and I dedicate this book to her.

PROLOGUE

The Masters Tools Will Never Dismantle the Masters House

Audre Lorde

The first time I laid eyes on the Benin Bronzes was in the spring of 2007. I had recently begun a relationship with a young British Nigerian woman, who identified strongly with her family links to Benin City. Being dimly aware that the British Museum held a collection of magnificent artworks from the historical Kingdom of Beninin what is now southern Nigeriaand that they remained unfamiliar to both of us, I took her to see them on one of our earliest dates. This illustrates the particular but largely unacknowledged advantage of romantic involvement with a historian.

Inside the sprawling neoclassical complex of the British Museum, the African collection is downstairs, in a gallery namedfor financial reasonsafter a British supermarket magnate. Down some shiny stone steps and through heavy swing doors, it is a cool space of marbled calm, offering some respite from the echoing bustle of the Great Court crowds above. The displays mix a number of pieces of contemporary art from Africa with a great many historical artefacts, some beautifully decorative, others of largely academic interest. Almost all were obtained, one way or another, during the long period of the British Empire.

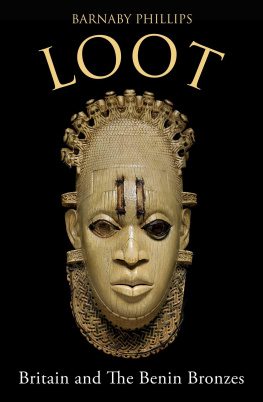

At the western end of the long gallery is the room housing the collection of works from the Kingdom of Benin. Enter the room, turn left, and immediately you are struck by the grand array of Benin plaques, surely the most famous of all the artworks from the kingdom. Suspended on slim rods, a grid of at least fifty of these dazzling pieceseach roughly the size of a large bookfills the room, floor to ceiling. Lit gently, almost reverentially, as befitting their pricelessness, they dominate the room, filling it with the glow of their chocolate colouring.

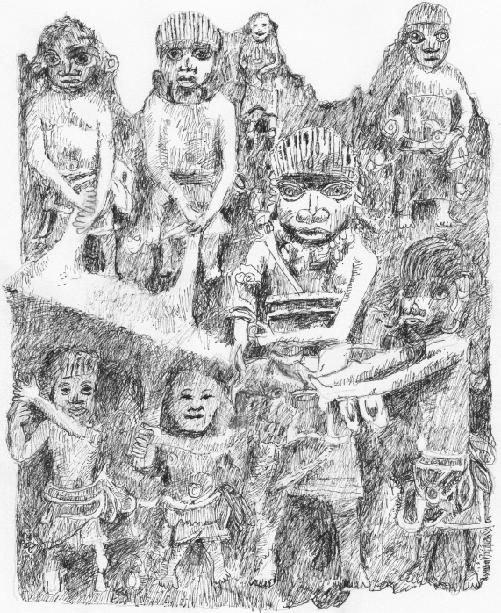

The Benin Bronzes is a collective term used loosely to refer to artworks made not only in bronze but also in brass and similar alloys, alongside other Benin pieces in ivory and various woods. The plaques are cast in brass but are no longer shiny, having aged over the centuries into tawny browns with reddish hints, as if dusted by cocoa powder. In intricate detail they show dozens of scenes from the history and myth of the Kingdom of Benin: kings and courtiers, soldiers and celebrants, monsters from imagination and merchants from abroad. The complex high-relief castingshowing figures almost emerging from the surfaceis evidence of superlative skill and, on this scale, of highly organised production; the plaques on show here are merely a tiny fraction of the Benin body of work.

Most striking perhaps is the highly stylised rendering of human features: boldly abstracted, with angular geometry, seemingly modern in style centuries before European Modernism. Faces are shown with large nostrils, eyes wide and heavily rimmed, staring intensely. In almost all plaques, the figures depicted look directly outwards, as if at the viewer, giving them an immediacy and special connecting power.

Focusing on one plaque almost at random among the dazzling array, one might see a central figure dominating the scenea great general, or perhaps the king himself. His skull, jaw and neck are clad tightly in a helmet and raised collar patterned in a way that represents coral beading, showing high status. He wears a necklet of leopards teeth, pointing outwards aggressively. His bare chest is crossed by a thick bandolier of coral beads, and he wears broad armlets of the same precious material. His body bears a series of marks, either tattoos or perhaps decorative scarification. A wrap around his waist is intricately patterned and may be edged with coral.

In his right hand this striking figure brandishes a sword with an extravagantly wide, curved blade in a shape reminiscent of a fish. He is flanked by two bearded warriors, shown slightly smaller and both dressed similarly: tall helmets that remind one of British Grenadiers of the eighteenth century, and what seems to be armour on their chests. Both soldiers carry short spears with lengthy, decorated blades. They look like stabbing spears, but does the fact that both warriors hold them pointing down mean that they were meant to be thrown? In a curious gesture, the king or commander also grasps one of the held spears in his left hand.