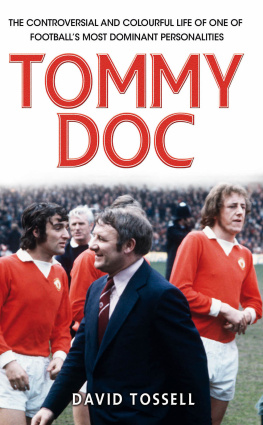

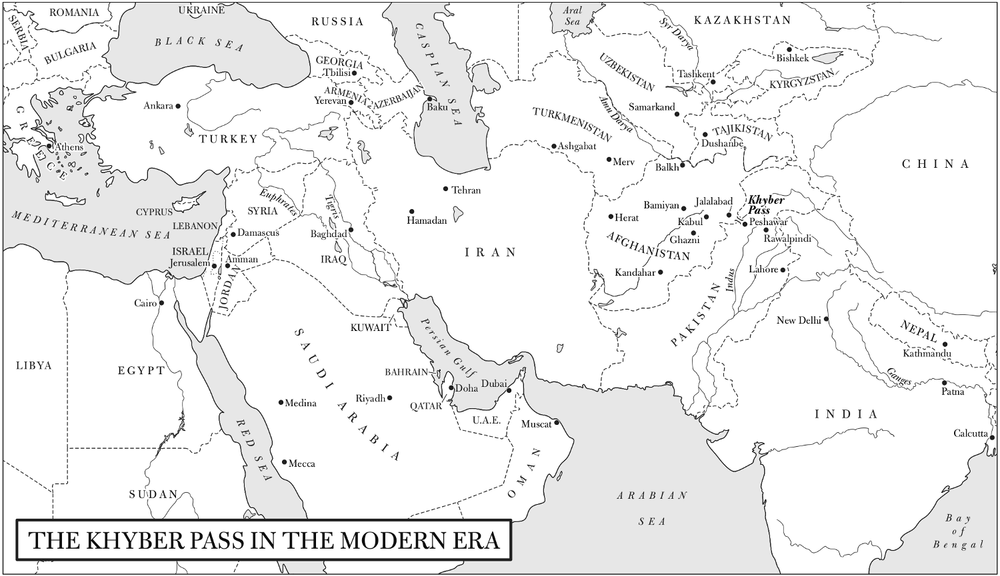

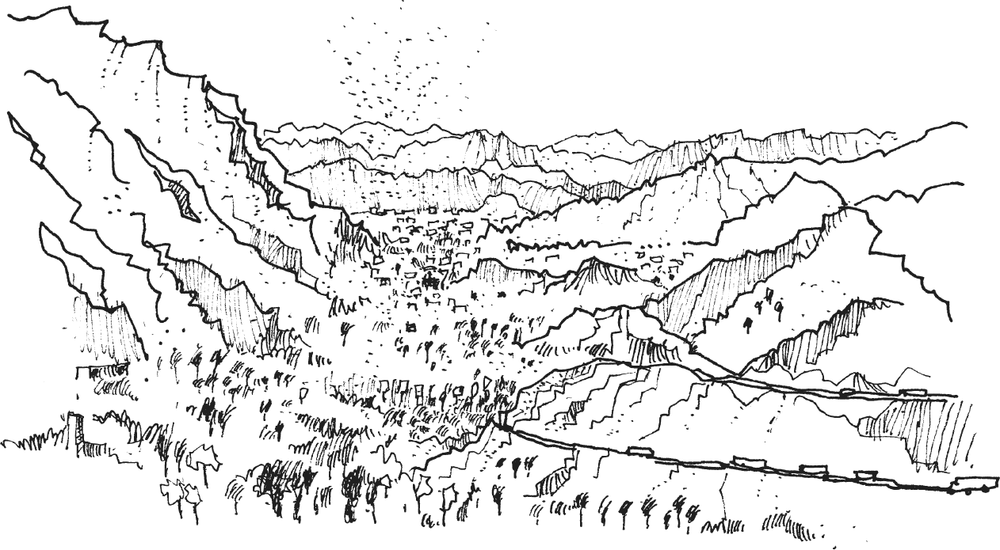

The western exit from inside the Khyber Pass

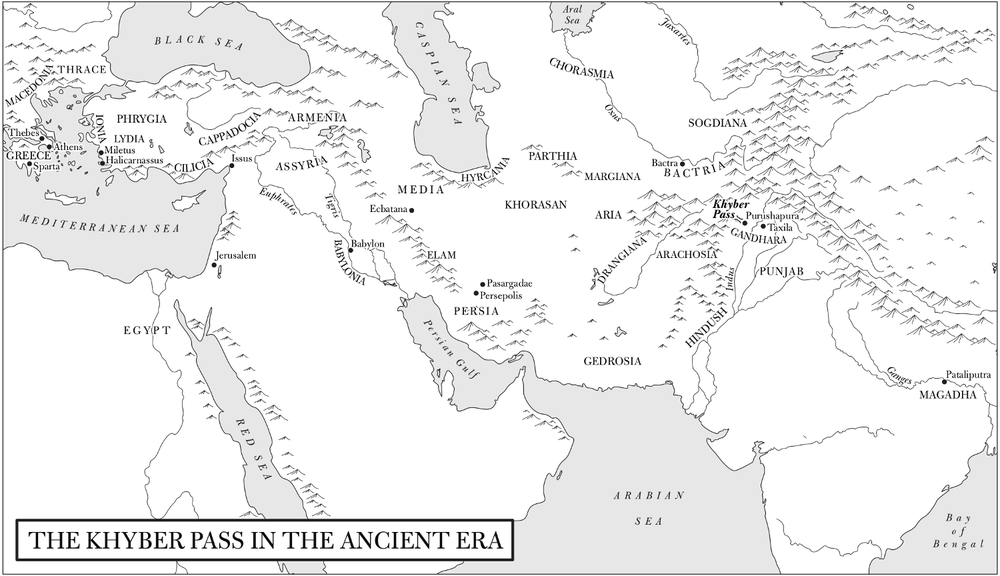

It was the bitter endgame of the disastrous First Afghan War. John Nicholson was riding through the Khyber Pass towards India, heading for the frontier and safety. A young subaltern in the army of British India, his regiment had been sent to Afghanistan following the invasion of 1839, and had remained while British fortunes in the country declined and then collapsed. As the main British army marched to its complete destruction on the terrible retreat from Kabul in January 1842, Nicholson and a handful of other British officers had been captured in Ghazni and endured several months of cruel captivity in Afghan hands. Then a new British force known as the Army of Retribution had mounted a second invasion, taking their vicious revenge on the Afghan population and leaving Kabul in flames. Nicholson had been freed, and on the morning of 4 November 1842, the journey through the Khyber Pass the legendary passage into India was all that lay between him and allied territory.

The march from Kabul had been grim and dangerous. The dead of January still littered the roadside all the way from the Afghan capital to the city of Jalalabad, halfway to the Khyber: an army of over 16,000 soldiers and camp followers had been destroyed in just a few days as they struggled to quit Afghanistan along the difficult, mountainous route to India. Countless skeletons lay scattered about as a testament to the lethal thoroughness of both the Afghan tribesmen and the severe winter weather. Now these two killers had returned to harass the homeward journey of the Army of Retribution; though proclaimed by the British as the triumphant return of a conquering force, the withdrawal risked becoming a second costly retreat.

Despite the dangers of ambush and icy weather, Nicholson and his unit had arrived safely at the western entrance of the Khyber Pass on 1 November. Here he enjoyed some consolation for his sufferings of the last few months: he was reunited with his younger brother, Alexander, after a separation of almost four years. Having followed John into a military career, Alexander had sailed out to India earlier that year and had just arrived on the frontier with his regiment to cover the withdrawal of the army from Afghanistan. Given their youth John Nicholson was nineteen, Alexander just seventeen and the anxious circumstances in which they found themselves, it must have been an emotional meeting, but neither man left a written account. After two days together, the Nicholson brothers were again split up: John remained with the rearguard while Alexander set off into the Khyber Pass on 3 November, his regiment providing escort for an army division on its journey to India. John followed a day later.

Thus John Nicholson came to be riding through the Khyber Pass on a November day in 1842 amid the hurried, anxious withdrawal of a vulnerable army. Once through the thirty miles of this famous mountain route, he would be clear of Afghan territory and could rest at last after two years of war and captivity. Though short in distance, the narrow width and rocky heights of the Khyber Pass made it especially in a time of war the most precarious stretch of the road to India. The Pathan tribesmen of the Khyber were especially renowned for their ferocity, even in a country of fighting men, and were feared for their ability to close the road to unwelcome armies, or at least to make them pay the price. Hilltop forts kept watch over the full length of the Pass, simple strongholds that were manned by tribesmen in times of crisis, giving them a clear shot over most of this crucial passage. Set above cliffs and reached only by an arduous climb, they gave warning of intruders in the Khyber and allowed tribesmen to fire on the road at their leisure. In the most constricted stretches, where tan-coloured rock confines the road tightly, these tiny citadels commanded the passage with particular power (see colour plate 1). Elsewhere, still under the gaze of these box-like forts, lengths of the Pass widen out, the grand walls of rock drawing back from the road to stand a mile apart. Here the scattered houses and sentinel towers must have seemed less forbidding as Nicholson rode by with his regiment, the claustrophobia of the straits perhaps diminished by the broader sky, and the rugged scenery even acquiring a fleeting beauty. Such openness was deceptive, a momentary relief before the Pass closed up suddenly once again, like a muscle contracting.

Nicholson and his men would surely have felt at their most vulnerable at Ali Masjid, near the middle of the Pass: sheer cliffs rise up dramatically to some 500 feet, allowing the road just a few feet to squeeze through. The narrow heights of the Ali Masjid gap make it the most easily defended point in the Pass, a bastion from which a few sniping tribesmen can delay an entire army with ease.