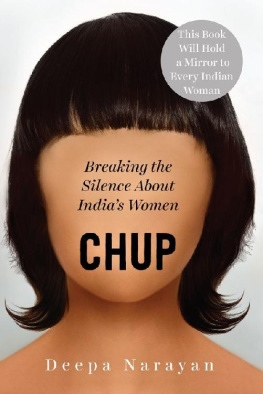

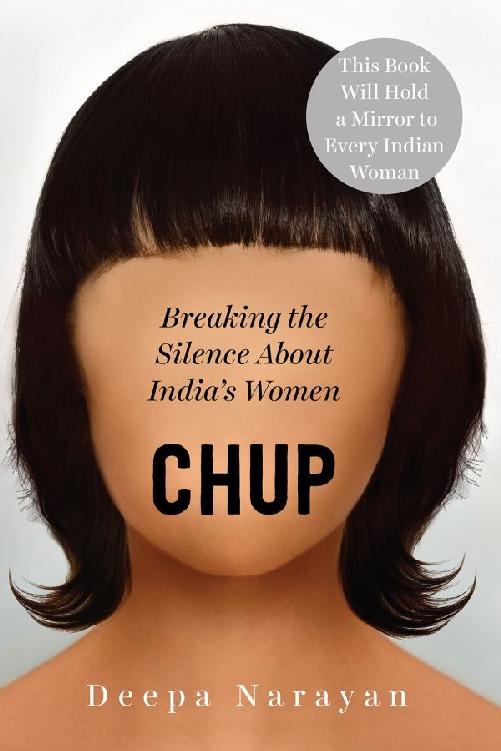

Narayan - Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women

Here you can read online Narayan - Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Juggernaut Books, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women

- Author:

- Publisher:Juggernaut Books

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Narayan: author's other books

Who wrote Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

I did not set out to do research or to write a book. Having written seventeen books on poverty policies and poor peoples empowerment published by the World Bank and academic presses, I had decided not to write any more. But this book forced itself upon me. It emerged from my determination not to be complacent after the rape of Jyoti Singh, or Nirbhaya. The brutality of the rape, the public outrage, the non-stop news coverage and the fact that it happened in my Delhi shook me, like millions of others, to the core. The public debate focused on law and order and the police and to a much lesser extent on the issue of culture.

As a trained social scientist I decided to turn to the cultural question. But culture is a big idea. What is it about a culture that can explain both rape and everyday sexism? The question began to obsess me. I was invited to give talks on poverty and development in Delhi, and I said I would go if I could explore the gender question. As I talked to young women and men at the renowned St Stephens College in Delhi one afternoon, I was startled by what I heard. One young woman said her seven-year-old niece, who loves chocolates, gave her only piece of chocolate, without being asked, to her nine-year-old cousin brother when he demanded more than his share. The reverse never happened. Nor was it expected. The definitions of a woman given by some of the brightest male and female students dripped with words like nice, caring, compromising.

After what I heard from women and men at St Stephens, I went to Gargi College, Lady Shri Ram College and Amity University. And then one more college. And so it continued. I could not stop. I also met women and men in their homes, in cafes, in universities, in malls, in offices, in airports and in parks. I met women, men and children living mostly in Delhi, but also in Bengaluru, Mumbai and Ahmedabad. I was surprised by what I heard from women who were competent, educated, gender aware and often fighting for gender rights. Often men seemed less conservative, until the discussion turned to what a couple should do after the birth of children. I met young people in slums. I met Indian students and women of Indian origin in Seattle, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and New York. Sometimes it seemed that only their clothes had changed.

What I heard women saying was disturbing. Over and over I would shake my head in disbelief that yet another smart and smartly dressed woman, an artist, a business manager, a financial analyst, a professor, a dentist, an engineer, a lawyer, a researcher, a scientist, a teacher, an educated stay-at-home mom was so unsure of herself. Or that she sounded, after the obligatory gender equality claims and sometimes passionate lecture, like her mother would have sounded thirty or forty years ago.

As unexpected inner realities unfolded, I became aware that I had taken on too much. I decided to focus on trying to make sense of womens complex lives, and I stopped interviewing men after fifty in-depth interviews to give me a comparison. This was a difficult decision. We do need a book on men, on their inner lives, thoughts, confusions, hesitations and burdens.

I also decided to focus on younger women, between the ages of 17 and 35, because every time I spoke to someone or saw a discussion on television, people asserted that young women today are modern and are very different from the past generations. I did not want my findings to be dismissed because the women I interviewed belonged to an older generation. Of course there have been changes. But the outer changes may have just camouflaged what has not changed. Sex ratios at birth or child sex ratios have worsened since Independence even as incomes have gone up. Female fetuses and girls 06 years old are still being killed or dying in large numbers.

It became obvious that I needed a team. I developed an interview guide using a methodology similar to the approach I followed in conducting the Voices of the Poor study, which involved 60,000 people in sixty countries, while I was at the World Bank in Washington, DC. I wasnt interested in abstractions or in how women and men should behave, but how women and men actually behave in their everyday life. And so I used open-ended questions that do not suggest any answers. Such research does not yield numbers or percentages, but throws up patterns of behaviour and beliefs that you did not know existed. Only very occasionally did I count the number of times something was mentioned. In this more open- ended context the researcher becomes a deep, empathetic, non-judgemental listener.

I trained six women from the middle and upper classes living in different parts of Delhi, and they conducted interviews in different geographic areas based on a simple sampling plan to contact women who fit certain age and income demographic criteria. In all, we conducted 600 interviews with women, men and schoolchildren in Delhi and some other metros. I have changed names and occasionally key identifying details to protect the women who trusted us enough to speak to us.

I ended up with approximately 8000 pages of notes from interviews with highly educated women in the cities. I took an inductive approach, letting the data speak to me, reading and rereading interviews and systematically aggregating data into larger and larger analytical groupings. I also used text analysis and searched for keywords. It takes time and patience to detect patterns. I trained new researchers who had not done any of the interviews to analyse them, to search and categorize the same data independently so as to minimize interpretation errors. This took another half-year.

As I analysed the interviews and read and reread them, the power of cultural habits, emotions and morality over education and the rational intellect pierced through the reams of documentation. There is a wide gap between our intellectual beliefs and our actual behaviour. This book is about the power of everyday culture over the intellect. It is about the all-pervasive cultural indoctrination that starts with childhood and prepares women to be deleted and then enrols women to delete themselves as well as other women, all without their conscious awareness.

The old explanation for gender inequality is patriarchy. This concept serves to highlight systemic bias against women, but it has been so overused it has become flaccid it merely stops conversation and therefore action. In addition it blames men, without whose participation change in gender relations cannot happen. We need new ideas.

There was much I did not know when I started this inquiry. I had not foreseen the deep emotional impact the interviews would have on my team and me. It was cumulative. It crept up on us. Young women doing the interviews started telling me that listening to womens stories was stirring up trouble in their own psyches. Nor had I foreseen the torrent of emotions talking would release in women being interviewed. I had been afraid women would have no patience for the interviews, but instead they started thanking us for letting them talk about issues they had kept bottled up. It was like witnessing the breaking of dams. In the absence of any judgement, the interview process became a safe emotional space. My researchers wrote their own stories. Some continued over several months. I offered support based on my experience in leading groups in emotional literacy. Mostly I just listened. It started affecting me as well, stirring up my memories.

I scoured the extensive research literature from India and the USA, some of which is referenced at the end of the book. Despite many good departments of psychology, social sciences and management in India, most of the behavioural studies on gender differences are from the USA; the few published behavioural studies on women and men in the middle and upper classes in India focus on buying behaviour. It is clear that the behaviours of educated American women are very similar to those of educated Indian women in cities, a remarkable fact given the different histories of the countries. Government National Family Health Surveys, census data, crime statistics and surveys by non-governmental organizations provide most of the Indian statistics used in this book.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women»

Look at similar books to Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.