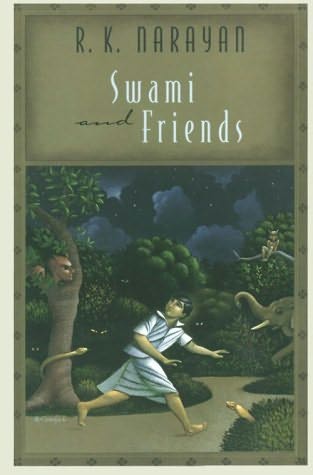

Swami and Friends

by

R. K. Narayan

CHAPTER I

Monday Morning

It was Monday morning. Swaminathan was reluctant to open his eyes. He considered Monday specially unpleasant in the calendar. After the delicious freedom of Saturday and Sunday, it was difficult to get into the Monday mood of work and discipline. He shuddered at the very thought of school: that dismal yellow building; the fire-eyed Vedanayagam, his class-teacher; and the Head Master with his thin long cane....

By eight he was at his desk in his 'room', which was only a corner in his father's dressing-room. He had a table on which all his things, his coat, cap, slate, ink-bottle, and books, were thrown in a confused heap. He sat on his stool and shut his eyes to recollect what work he had for the day: first of course there was Arithmetic--those five puzzles in Profit and Loss; then there was English--he had to copy down a page from his Eighth Lesson, and write dictionary meanings of difficult words; and then there was Geography.

And only two hours before him to do all this heap of work and get ready for the school!

Fire-eyed Vedanayagam was presiding over the class with his back to the long window. Through its bars one saw a bit of the drill ground and a corner of the veranda of the Infant Standards. There were huge windows on the left showing vast open grounds bound at the other extreme by the railway embankment.

To Swaminathan existence in the classroom was possible only because he could watch the toddlers of the Infant Standards falling over one another, and through the windows on the left see the 12.30 mail gliding over the embankment, booming and rattling while passing over the Sarayu Bridge. The first hour passed of quietly. The second they had Arithmetic. Vedanayagam went out and returned in a few minutes in the role of an Arithmetic teacher. He droned on monotonously. Swaminathan was terribly bored. His teacher's voice was beginning to get on his nerves. He felt sleepy.

The teacher called for home exercises. Swaminathan left his seat, jumped on the platform, and placed his note-book on the table. While the teacher was scrutinizing the sums, Swaminathan was gazing on his face, which seemed so tame at close quarters. His criticism of the teacher's face was that his eyes were too near each other, that there was more hair on his chin than one saw from the bench, and that he was very very bad-looking. His reverie was disturbed. He felt a terrible pain in the soft flesh above his left elbow. The teacher was pinching him with one hand, and with the other, crossing out all the sums. He wrote 'Very Bad' at the bottom of the page, flung the note-book in Swaminathan's face, and drove him back to his seat.

Next period they had History. The boys looked forward to it eagerly. It was taken by D. Pillai, who had earned a name in the school for kindness and good humour. He was reputed to have never frowned or sworn at the boys at any time. His method of teaching History conformed to no canon of education. He told the boys with a wealth of detail the private histories of Vasco da Gama, Clive, Hastings, and others. When he described the various fights in History, one heard the clash of arms and the groans of the slain. He was the despair of the Head Master whenever the latter stole along the corridor with noiseless steps on his rounds of inspection.

The Scripture period was the last in the morning. It was not such a dull hour after all. There were moments in it that brought stirring pictures before one: the Red Sea cleaving and making way for the Israelites; the physical feats of Samson; Jesus rising from the grave; and so on. The only trouble was that the Scripture master, Mr Ebenezar, was a fanatic.

'Oh, wretched idiots!' the teacher said, clenching his fists, Why do you worship dirty, lifeless, wooden idols and stone images? Can they talk? No. Can they see? No. Can they bless you? No. Can they take you to Heaven? No. Why? Because they have no life. What did your Gods do when Mohammed of Gazni smashed them to pieces, trod upon them, and constructed out of them steps for his lavatory? If those idols and images had life, why did they not parry Mohammed's onslaughts?'

He then turned to Christianity. 'Now see our Lord Jesus. He could cure the sick, relieve the poor, and take us to Heaven. He was a real God. Trust him and he will take you to Heaven; the kingdom of Heaven is within us.' Tears rolled down Ebenezar's cheeks when he pictured Jesus before him. Next moment his face became purple with rage as he thought of Sri Krishna: "Did our Jesus go gadding about with dancing girls like your Krishna? Did our Jesus go about stealing butter like that archscoundrel Krishna'? Did our Jesus practise dark tricks on those around him?'

He paused for breath. The teacher was intolerable to-day. Swaminathan's blood boiled. He got up and asked, 'If he did not, why was he crucified?' The teacher told him that he might come to him at the end of the period and learn it in private. Emboldened by this mild reply, Swaminathan put to him another question, 'If he was a God, why did he eat flesh and fish and drink wine?' As a brahmin boy it was inconceivable to him that a God should be a non-vegetarian. In answer to this, Ebenezar left his seat, advanced slowly towards Swaminathan, and tried to wrench his left ear off.

Next day Swaminathan was at school early. There was still half an hour before the bell. He usually spent such an interval in running round the school or in playing the Digging Game under the huge Tamarind tree. But to-day he sat apart, sunk in thought. He had a thick letter in his pocket. He felt guilty when he touched its edge with his fingers. He called himself an utter idiot for having told his father about Ebenezar the night before during the meal.

As soon as the bell rang, he walked into the Head Master's room and handed him a letter. The Head Master's face became serious when he read:

Sir,

'I beg to inform you that my son Swaminathan of the First Form, A section, was assaulted by his Scripture Master yesterday in a fanatical rage. I hear that he is always most insulting and provoking in his references to the Hindu religio n. It is bound to have a bad effect upon the boys. This is not the place for me to dwell upon the necessity for toleration in these matters.

I am also informed that when my son got up to have a few doubts cleared, he was roughly handled by the same teacher. His ears were still red when he came home last evening.

The one conclusion that I can come to is that you do not want non-Christian boys in your school. If it is so, you may kindly inform us as we are quite willing to withdraw our boys and send them elsewhere. I may remind you that Albert Mission School is not the only school that this town, Malgudi, possesses. I hope you will be kind enough to inquire into the matter and favour me with a reply. If not, I regret to inform you, I shall be constrained to draw the attention of higher authorities to these Unchristian practices.

I have the honour to be,

Sir,

Your most obedient servant,

W. T. Sreenivasan.'

When Swaminathan came out of the room, the whole school crowded round him and hung on his lips. But he treated inquisitive questions with haughty indifference. He honoured only four persons with his confidence. Those were the four that he liked and admired most in his class. The first was Somu, the Monitor, who carried himself with such an easy air. He set about his business, whatever it was, with absolute confidence and calmness. He was known to be chummy even with the teachers. No teacher ever put to him a question in the class. It could not be said that he shone brilliantly as a student. It was believed that only the Head Master could reprimand him. He was more or less the uncle of the class.

Next page