Contents

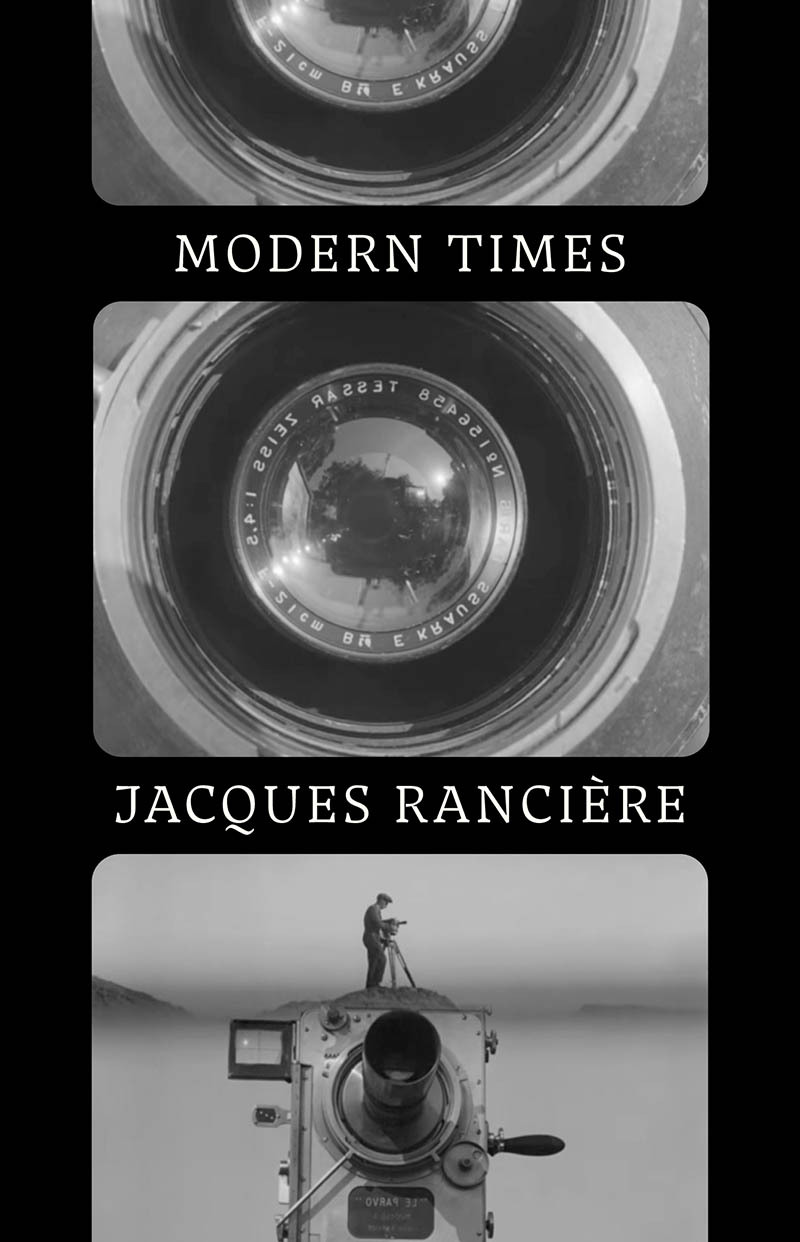

Modern Times

Modern Times

Temporality in Art and Politics

JACQUES RANCIRE

TRANSLATED BY

GREGORY ELLIOTT

This English-language edition first published by Verso 2022

Translation Gregory Elliott 2021

This expanded edition first published as Les temps modernes: Art, temps, politique

La Fabrique 2018

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

9781839763236

ISBN-13:978-1-83976-319-9

ISBN-13:978-1-83976-322-9(UKEBK)

ISBN-13:978-1-83976-323-6(USEBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021948555

Typeset in Fournier by MJ&N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

CONTENTS

Some explanation is doubtless required when one has the audacity to borrow the title of a famous film and a famous journal. The simplest, and most precise, consists in stating that, appearances to the contrary notwithstanding, the title in French Les temps modernes is not the same. The use of the plural accounts for the difference. It is normally a figure of speech to convey the modern age or condition. Sartre followed this usage when introducing the first issue of Temps modernes . There he invokes the writers total commitment in their age, conceived as a totality, a meaningful synthesis. advance a diagnosis. The reference to Charlie Chaplins film helps us to formulate the problem. Its dramaturgy is based on an obvious clash between two temporalities: the swaying movement of the tramp who takes his time and the inexorable rhythm of the machine that forces him into the compulsive gesture of someone who cannot stop tightening nuts and bolts, and who hallucinates that they are everywhere. But Chaplins contemporaries had already asked themselves this question: are the automatic character of the insouciant tramps gestures and the machines infernal rhythms really antithetical? In fact, prior to embodying denunciation of the industrial age in the name of some dubious nostalgia for romantic bohemia, Chaplin had embodied the precise opposite. The Soviet artistic avant-garde made him a fellow of Lenin and Edison: a man whose gestures were perfectly adapted to the punctuality of the machine about to sweep away the detritus of the old world. It is true that adherents of this avant-garde had themselves been treated as gentle dreamers by those who deemed themselves the real avant-garde: the leaders of the Soviet Communist Party, who were not concerned with the aesthetic synchronization of machines and gestures, but looked to them to accumulate the wealth that would form the basis of a future communism, at the cost of protracted effort and unremitting discipline.

Opposed movements, opposed modernities, opposed avant-gardes: the conflict over what modern times are has only intensified. In truth, it goes back a long way. In 1847, the Communist Manifesto saluted the historical work of a bourgeoisie that had prepared the socialist future by liquidating antiquated feudal structures and ideologies. Was Marx aware that he was adopting the thesis of counter-revolutionaries denouncing the fatal rise of modern individualism for the cause of a future collectivist revolution? In all events, there is no doubt that, a few years earlier, he had proposed a quite different analysis of the relations between past, present and future: if the revolution was going to occur in Germany, he had argued, it was on account of German retardation; more precisely, because of the discrepancy between the lead taken by German philosophy and the backwardness of the countrys feudal and bureaucratic structures. In the same years, in the United States, Emerson also diagnosed a discrepancy, summoning the future poet who would know how to bridge the gap between the countrys material development and its spiritual infirmity. And it was precisely in this lag, in the fact that modern America was still in pre-Homeric times when it came to culture, that he perceived the possibility of such a poet emerging. We know how Walt Whitman would realize his wish by donning the apparel of a new Homer, and providing future revolutionaries with the model of a poetry drawn from the prose of everyday life. Later on, his compatriots Loie Fuller and Isadora Duncan arrived to play the maenads of the electric age or to revive the movements depicted on ancient Greek vases for a dance of the future. In their wake, Dziga Vertov tasked three ballerinas with synthesizing the movements of the communist working day on screen, only the following year to see his colleague and enemy Eisenstein oppose to his modern symphony of machines a mythological bull ceremony, which to him was much more apt as a symbol of the collective dynamism of the new times.

We could extend the list of the contradictions and paradoxes we encounter in any discourse on modernity. But for now it is enough to confirm the following: there is no one modern times, only a plurality of them, of frequently different, and sometimes contradictory, ways of thinking the time of modern politics or modern art in terms of progress, regression, repetition, arrest or overlapping times; different or contradictory ways of organizing the temporalities of the arts of movement their continuities, breaks, forms of splicing and resumption to create works responding to present conditions and future exigencies. This interlacing, and these clashes of temporalities, were what I chose to talk about to endow with some coherence a series of lectures given at the instigation of friends in various countries of the former Yugoslavia. In Skopje, I queried the way in which the time of politics is narrated and sought, to rethink it not as a line stretching between a past and a future, but as a conflict over the distribution of life forms. In Novi Sad, on the basis of this conflict, I tried to redefine what is to be understood by the ambiguous term artistic modernity. In Zagreb and Sarajevo, I analysed the way that cinema, in order to speak of its time, combined the heterogeneous temporalities of narrative, performance and myth. A proposal was then made to me by the Multimedijalni Institut of Zagreb to publish a collection comprising these three talks. It seemed to me perfectly in keeping to add a talk on The Moment of Dance given elsewhere, but whose themes and issues chimed so well with theirs. Two of the talks were initially written in English, while the other two went through French and English versions. The original edition of this book was published in English in 2017 in Zagreb, under the title Modern Times: Essays on Temporality in Art and Politics . Eric Hazan then expressed a desire to publish a French version. Translating texts composed in a foreign language into ones mother tongue is a tolerable exercise only on condition of being an unfaithful translator. I have therefore not sought simply to furnish a French equivalent of the English version, but have taken the opportunity to rewrite passages and make various changes. Thus, what francophone readers have in their hands is a book that is faithful to its original, but new in its formulation. All those who made the existence of both editions possible will find my warmest thanks in the Acknowledgements.