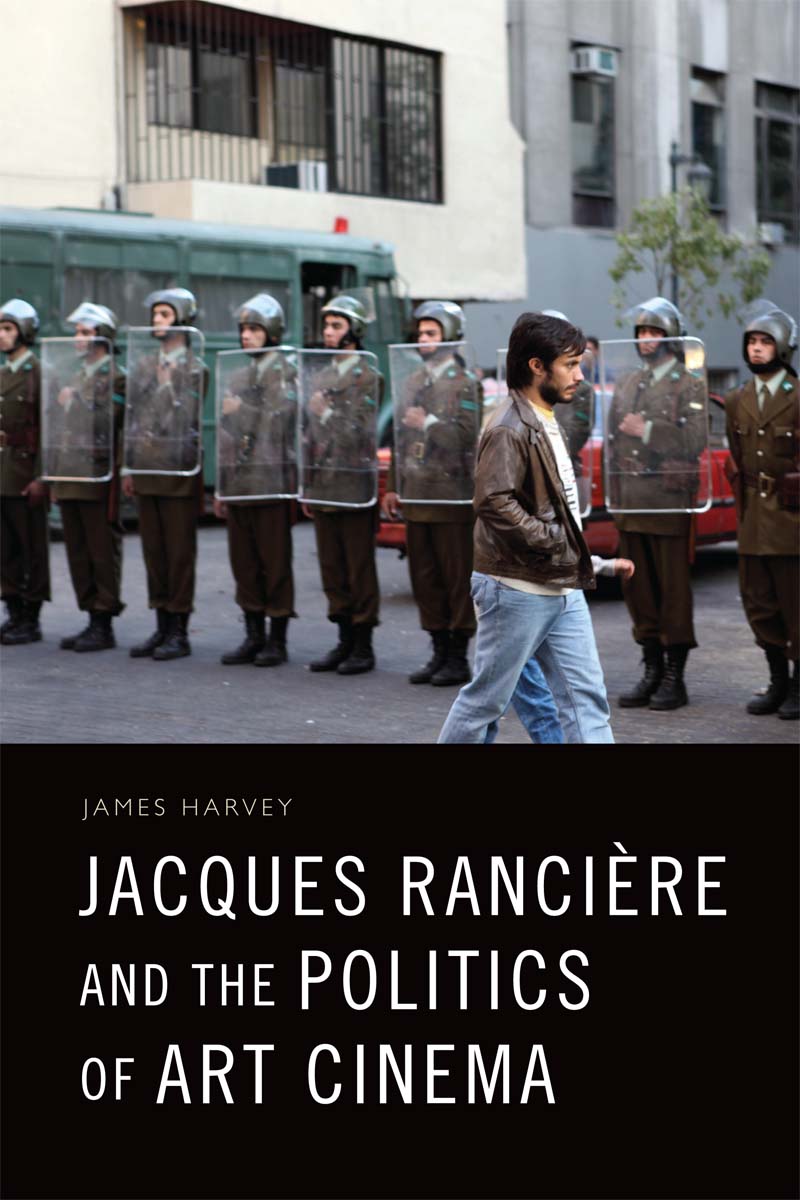

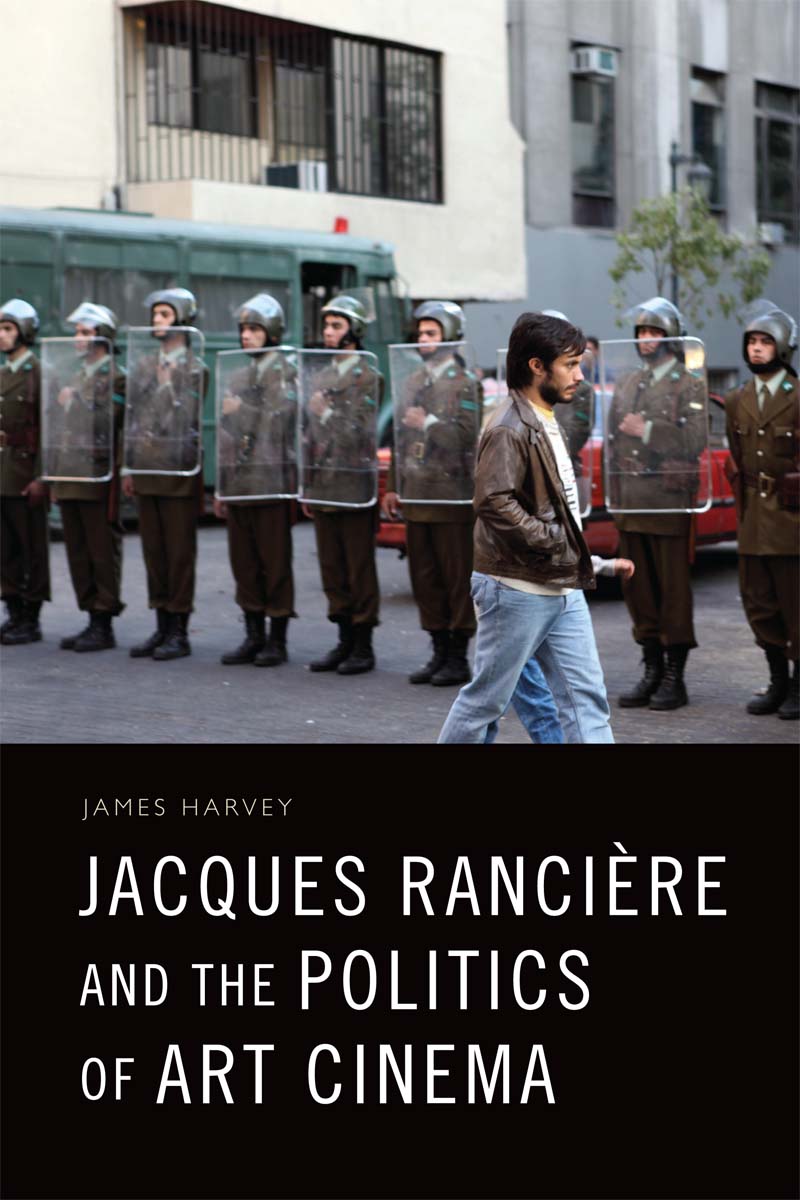

Jacques Rancire and the Politics of Art Cinema

Jacques Rancire and the Politics of Art Cinema

James Harvey

Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com

James Harvey, 2018

Edinburgh University Press Ltd

The Tun Holyrood Road

12 (2f) Jacksons Entry

Edinburgh EH8 8PJ

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 4744 2380 9

The right of James Harvey to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498).

Contents

Figures

Acknowledgements

The shape of this book has taken on many guises in the six years of its writing. It is fair to say that, through this process, I have come to appreciate the limits of, and potentialities for, cinemas ability to do politics. For helping me articulate my ideas, I must offer the greatest thanks to Tina Kendall: the best doctoral supervisor anyone could ever hope for.

Along the way, I have also been lucky enough to receive the friendly critical attention of: Richard Rushton, Tanya Horeck, Martin OShaughnessy, Bill Marshall, Angelos Koutsourakis, Shohini Chaudhuri, William Brown, Sarah Wright, Geoffrey Kantaris, Nike Jung, Aaron Hunter, Matilda Mroz, Tiago de Luca, Miriam de Rosa, Simon Payne, Rosalind Galt, Colin Wright, and Joss Hands, as well as many vital contributions from those kind enough to attend numerous talks I have given over the past few years.

This book is for my two sons, Joseph and Joshua.

Introduction: Politics and Art Cinema

W e know too well that the systemic social violences of inequality are social, historical and economic; that they are so immanently perceivable shows that they are aesthetic also. Who is seen and heard; who speaks and who is spoken to; in what ways one can communicate and how one experiences communication: these issues are still rigidly determined by hierarchies enshrined in tradition and are intensified more than ever in twenty-first-century global capitalism. The aesthetic is the philosophical category describing experience and perception and, as such, it plays a fundamental role in articulating how we experience a social life. The aesthetics of politics must, therefore, play a central role in challenging the mechanics of each social life. As a category of cinema most routinely and self-consciously described as aesthetic, art films provide acute spaces for the acting out of these challenges. This book is an attempt to shed light on the political potential of art cinema today. My hope is that if we contemplate carefully some notable works of global art cinema in the twentyfirst century, we may delineate in the films an extra-textual engagement with the social malaise in which we find ourselves at present. Geographically and stylistically disparate, the films analysed in this book provide diverse and novel responses to issues that are often global in nature. Even in their social and historical contexts, each of the films discussed allows us to engage with a concept as familiar in sound as it is alien in reality: politics. The aim of this book, therefore, is to argue that such a thing as politics exists in contemporary art cinema.

DEFINING POLITICS

Few thinkers have had more inspiring, innovative things to say about the politics of aesthetics in recent years than Jacques Rancire. Two points made by Rancire in Disagreement (1999) his seminal text on political philosophy have provided the inspiration for the arguments made herein. The first regards the way we conceive of politics. For Rancire, it is a word that has been over-assigned; that has been near emptied of its radical historical promise of change and flux; and, as such, has been made synonymous with the day jobs of elected representatives: the people who, supposedly, do politics. However, these people are not doing politics at all. Rather, for Rancire, the activities of state politicians are far more likely to represent something at odds with the actual occurrence of politics: order. Those charged with the responsibility of doing politics on behalf of the people represent an instrument of power that ultimately works to consolidate order, reinforce the appearance of politics in civilised society and, in turn, play a starring role in determining how we experience social life. Taking up Rancires position on this matter, I assume an alternative thesis: politics runs against orderly society in its defining nature. Politics is not an activity that protects the dispossessed or preserves order it is interruptive:

The struggle between the rich and the poor is not social reality, which politics then has to deal with. It is the actual institution of politics itself. There is politics when there is a part of those who have no part, a part or party of the poor. Politics does not happen just because the poor oppose the rich. It is the other way around: politics (that is, the interruption of the simple effects of domination by the rich) causes the poor to exist as an entity. The outrageous claim of the demos to be the whole of the community only satisfies in its own way that of a party the requirement of politics. Politics exists when the natural order of domination is interrupted by the institution of a part of those who have no part. (Rancire 1999: 11)

Laying firm foundations for a strict, Greek definition of politics, Rancire immediately sets himself up in opposition to many of the key political thinkers of the twentieth century. One might spend time delineating the difference between this mode of thinking politics from conservative thinkers such as Leo Strauss or Carl Schmitt; the liberalism of Max Weber or Karl Popper; or the revised Marxisms of the 1970s, from which Rancires own early thought derived and detached itself. However, such is the currency of Rancire in contemporary philosophical discourse, several fine texts have already achieved this feat.to have been torn from its essential interruptive activity performed by those who have no part in society. It is mounted instead onto a customised scene of class struggle. Rancires break with Althusser concerned this very dispute a disagreement regarding who has the capacity and social positioning to utter politically. As he argues in Althussers Lesson (2011a), Althusser spoke on behalf of the people, from the position of an intellectual. There is a clear way of differentiating the meaning of politics for Rancire from the common usage of a politics. There is no such thing as a politics; politics is a concept with its own predetermined activities and functions, which can be described as the interruption of the social order by those excluded from it, in turn expressing the existence of a part of those who have no part.

The interruptive moment of politics cannot be provided from above. We must assume, then, with Rancire, that politics can only derive from the sites occupied by parties excluded from society (the part of those who have no part). He makes this very point in Disagreement:

Politics... actually happens very little or rarely. What is usually lumped together under the name of political history or political science in fact stems more often than not from other mechanisms concerned with holding on to the exercise of majesty, the curacy of divinity, the command of armies, and the management of interests. Politics only occurs when these mechanisms are stopped in their tracks... (Rancire 1999: 17)

Next page