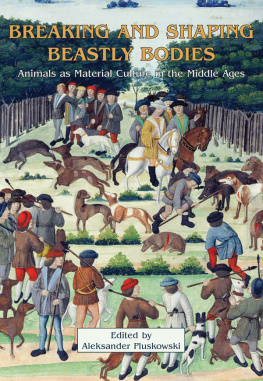

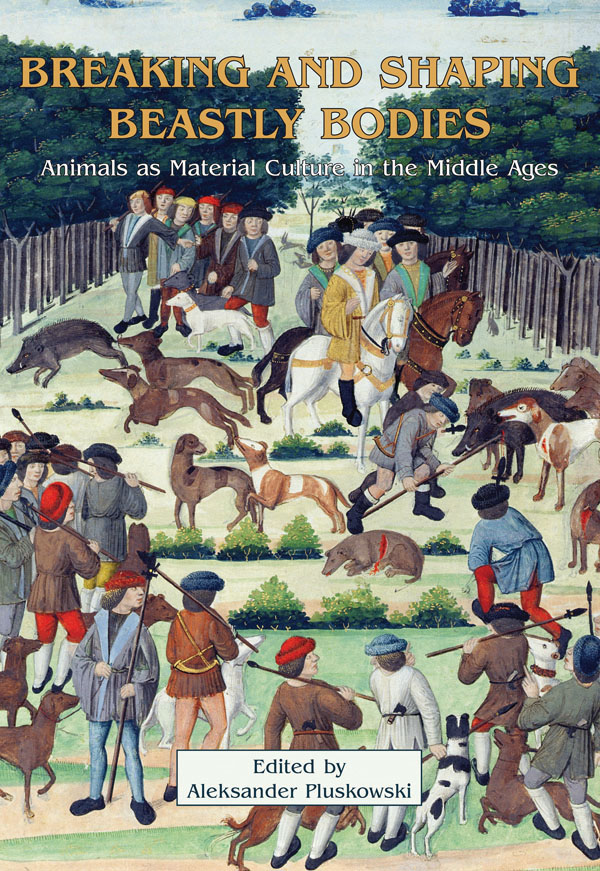

Aleksander Pluskowski - Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies. Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages

Here you can read online Aleksander Pluskowski - Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies. Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2007, publisher: Casemate Publishers & Book Distributors, LLC, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies. Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages

- Author:

- Publisher:Casemate Publishers & Book Distributors, LLC

- Genre:

- Year:2007

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies. Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies. Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies. Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies. Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

B REAKING AND S HAPING B EASTLY B ODIES

Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages

Edited by

Aleksander Pluskowski

Oxbow Books

First published in the United Kingdom in 2007. Reprinted in 2017 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Oxbow Books and the individual authors 2007

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-84217-218-6

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-867-1 (epub)

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-868-8 (Mobi)

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

| UNITED KINGDOM | UNITED STATES OF AMERICA |

| Oxbow Books | Oxbow Books |

| Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449 | Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146 |

| Email: | Email: |

| www.oxbowbooks.com | www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow |

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

Cover image: Louis Malet (14411516) Seigneur de Graville, hunting wild boar, from the Terrier de Marcoussis, 149193 (vellum). French School, The Bridgeman Art Library, Getty Images.

Peoples attitudes to animal bodies go right to the heart of the business of being human. Our increasingly detailed, yet spectacularly incomplete, knowledge of the behavioural complexity of other species has serially quashed many of the claims that have been made for human uniqueness. We use the manufacture of simple artefacts as a proxy indicator of human-like behaviour amongst early hominins, yet Man the Tool-Maker shares that skill with, amongst others, chimpanzees, crows and sea-otters (Boesch 2003). Similarly, as the fossil record pushes upright walking further back into the Pliocene, Man the Biped no longer looks quite so clever (Harcourt-Smith and Aiello 2004). Is there anything, apart from industrialised warfare and cricket, which our species is uniquely good at?

An important human trait is our inclination to develop complex relationships with numerous other species. In its simplest form, this is not unique. Mutualism exists throughout the biosphere, with some pairs of species, such as ants and aphids, evolving elaborate and highly successful relationships to mutual benefit (De Mazancourt et al. 2005). In the great majority of cases, however, these mutualistic relationships involve a pair of species, whose co-evolution has been achieved through behavioural adaptation driving positive selection pressures. Humans go a step further, opportunistically and, it sometimes seems, almost arbitrarily elaborating our relationships with many other species, whether through domestication, pet-keeping, taming for menageries, fetishising, deifying, anthropomorphising, exterminating vermin, conserving iconic species, or recruiting as mascots (what is it about military regiments and goats?). That complex web of relationships extends after the death of the animal, ranking some animal foods or particular skins and furs above others. In some instances, we can argue that these rankings reflect availability or some particular functional attribute of a raw material. A well-known example is the selection of reindeer and wolverine fur for different components of the traditional Inuit parka, making optimal use of the different insulating properties of two readily-available animal resources (Cotel et al. 2004). In other instances, restricted availability may cause a raw material to be ranked more highly than one of almost indistinguishable appearance and working properties. Thus, a netsuke figure carved from the upper incisor tooth of an elephant will be prized over one carved from a tangua nut, which in turn outranks one cast from plastic (). Human attitudes to other animals, it seems, are characteristically complex and range from the strictly utilitarian to the highly conceptualised and culture-specific. When we consider medieval attitudes to animals before and after death, therefore, we are tackling a fundamentally human, and distinctly idiosyncratic, behavioural trait.

Fig. 1.1. Frog and mouse figure, carved in tangua nut to mimic ivory.

Those of us who approach medieval animals primarily through the zooarchaeological record of old bones have to balance three strands of investigation. The bones are the fossils of long-dead animals, which had their own distinctive biology and ethology. Their death assemblage, and therefore the recovered assemblage that we study, will to some degree reflect that biology and ethology. For example, bones of frogs are occasionally very abundant in medieval archaeological deposits (e.g. OConnor 1988, 1067, 113). We do not need to postulate mysterious anuran cults to explain this phenomenon: frog behaviour and ecology lead them to be locally abundant in life and particularly susceptible to catastrophic death en masse . The same does not apply to cats, so a concentration of cat bones in a medieval pit would require a different form of explanation (Luff and Moreno-Garcia 1995). The bones are also sediment clasts, sometimes the most abundant large particles in an archaeological sediment (Wilson 1996). A range of familiar geomorphic processes, such as downslope colluviation and hydrodynamic sorting, will cause the differential movement of different particle sizes, and may thus bring about patterning in the distribution of bones in the archaeological record. Although the world of medieval archaeology may seem somewhat removed from the more familiar terrain of geomorphology, those same processes will be acting on dumps and yard surfaces and in pitfills. We need a taphonomic analysis of our medieval material just as much as we would for a Lower Palaeolithic assemblage, in order to identify the signature that the processes of death, biostratinomy and diagenesis have left on our assemblage. Finally, of course, the bones are the residue of past human activity, susceptible to archaeological study, and reflecting the decisions and pre-occupations of people of a particular time and place. That decision-making will have influenced the composition of the life-assemblage from which our archaeological sample derives (e.g. by deciding that a particular species shall be excluded from the diet), and it will have affected the post-mortem taphonomy of the bones (e.g. by imposing rules regarding the disposal of organic refuse). As zooarchaeologists, our distinctive challenge is to understand bones as fossils and clasts, in order to understand them all the more clearly as evidence of that decision-making, and thus as archaeology.

Like charity, ethnography begins at home. Our own attitudes to animals as food, labour, clothing and symbol make a useful starting point for discussing medieval beasts. Even the familiar role of animals as food is richly complex and contentious. In some contemporary societies, many individual people and certain religious sects contend that the use of animals for food is essentially immoral. The time-depth of vegetarianism on moral precepts is unknown, and this is not the place to plumb that particular abyss. We should note, however, that intermittent avoidance of meat on fast days has long been a feature of western Christendom, and thus of medieval Europe. How far that avoidance was driven by a sense of moral obligation towards the beasts, and how far by the need to manifest social identity by the imposition of consumption laws, is a matter for debate. Even the decision to eat or to avoid meat is tempered by pragmatism or indecision. In early 21st-century Britain, some vegetarians will consume fish and shellfish, thus apparently making a distinction between endothermic and ectothermic animals, with a lessened moral obligation towards the latter. Others will even eat poultry whilst avoiding red meats such as beef or lamb, implying a yet more subtle categorisation that owes little to biological taxonomy. Similar decisions are made by omnivores, too: the writer of this paper will cheerfully eat rabbit or horse, but not veal.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies. Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages»

Look at similar books to Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies. Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies. Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.