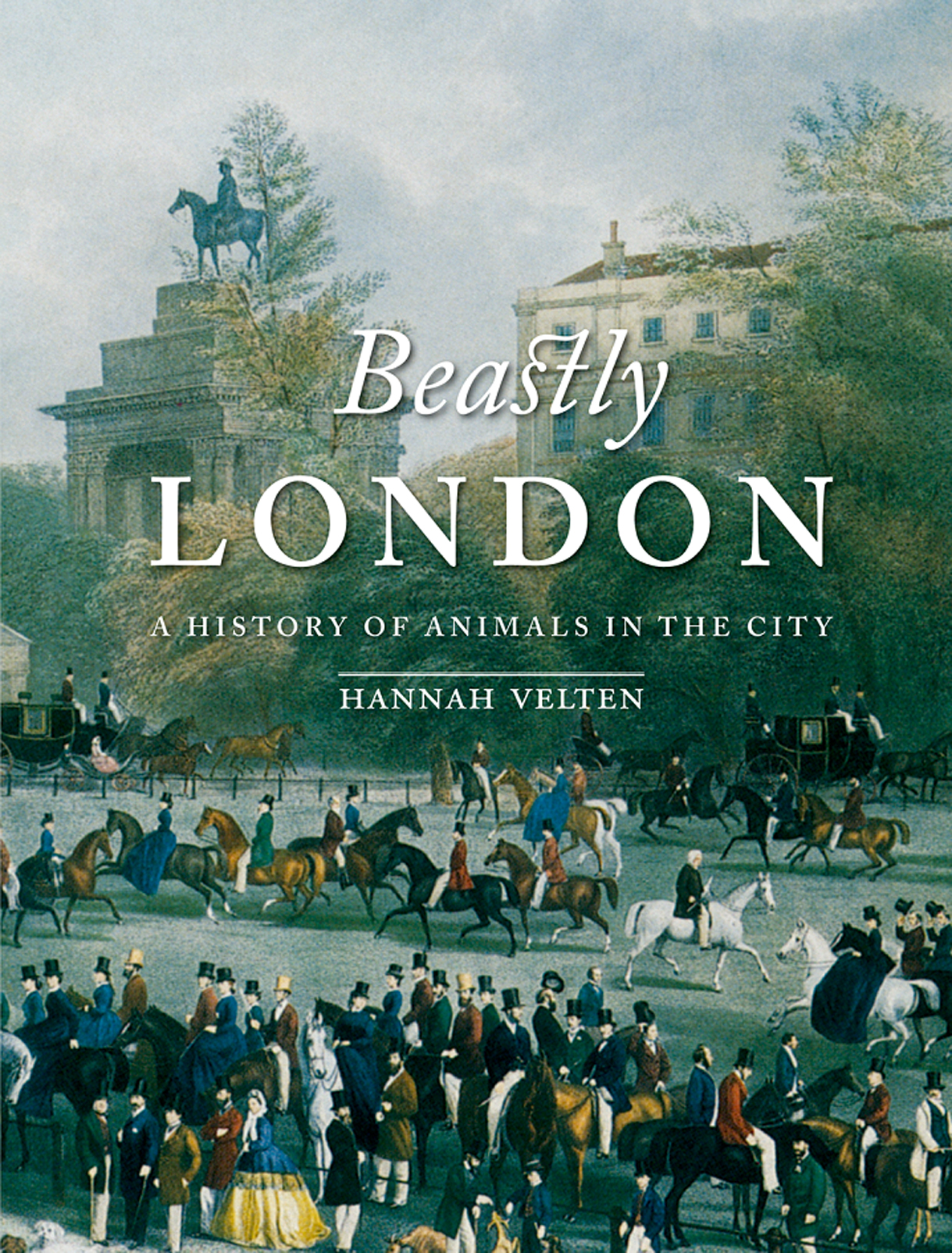

Beastly

LONDON

A HISTORY OF ANIMALS IN THE CITY

HANNAH VELTEN

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

33 Great Sutton Street

London ECIV ODX

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2013

Copyright Hannah Velten 2013

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgments and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China

by C&C Offset Printing Co., Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 9781780232171

Contents

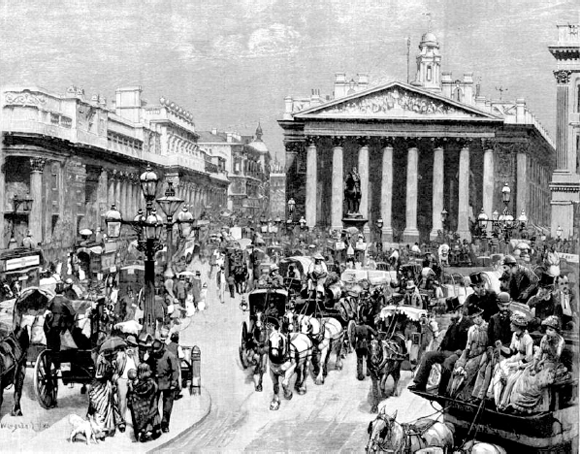

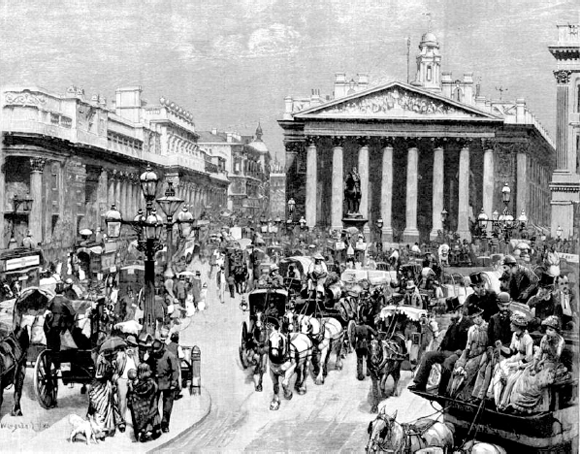

Horse-drawn chaos outside The Bank, 1886, engraving after a picture by W. Logsdail exhibited at the Royal Academy.

Introduction: Revealing the Beasts

A sk anyone living outside London, and even Londoners themselves, to name animals associated with the city and they are likely to list those associated with tourist sights or recent news items: the Queens state horses, used at the wedding of William and Kate in 2011; the ravens at the Tower of London; the members of the Household Cavalry on duty at Horse Guards; London Zoo; the waterfowl in the royal London parks; the cat that lives at 10 Downing Street; the Queens corgis; disorientated mammals swimming up the Thames; Battersea Dogs and Cats Home; urban foxes; and the exploding rat population.

These potent symbols of London society and culture provide a snapshot of the rich heritage of the animal inhabitants of London from Roman times to the present. But dig a little deeper into the history of beastly London, and it becomes obvious that todays scant animal population pales into insignificance compared with the heaving mass of animals that once lived on the streets, in the Thames and in Londoners homes. Instead of the roar of traffic, Londons soundtrack was, until relatively recently, a cacophony of man-made noise, neighing, barking, mooing, bleating, quacking, braying, hissing, oinking, roaring, screeching, clucking, tweeting, trumpeting, meowing, snarling, squeaking and snuffling. It is only recently within the last few decades that animals aside from pets, and those mentioned above, have more or less become extinct in the city: the last brewery dray horses have left, the pigeons of Trafalgar Square have been removed, the large animals of London Zoo have been evacuated, Club Row animal market is banned and the Smithfield Show and Crufts exhibitions have been relocated away from London. It can be argued that animals no longer have a place on the streets of twenty-first-century London because of the filth and nuisance they would cause. So far as the animals are concerned, it could be said that it is a good thing that they no longer have to endure urban life especially its pollutants, its man-made habitat and its hectic nature. However, London has lost some of its rich character with the withdrawal of animals.

The interaction between animals and Londoners of all classes was an integral part of everyday life and experience. It is difficult today to appreciate how closely they lived side by side, sometimes in the strangest of circumstances. In the 1850s barbers sold bears grease as a hair-growth stimulant and some particular and conscientious barbers even pretended to kill their own bears and boil them down to render the fat.

The animals of London were certainly used for all sorts of purposes. They were used to feed Londoners, to transport them and their goods, to entertain them, to provide a livelihood for them, to give opportunities for research and study, to provide sport and gambling opportunities, to soothe their urban souls, to provide secondary products and to act as fashionable accoutrements and companions. Wild animals and scavengers chose to live in London because the man-made environment met their every need. Even the dust in the streets that caused distress to all in the dry months was created by animals, especially the vast number of horses constantly passing over the thoroughfares.

However, it is rare to find more than a passing mention of the animal populations of London in general histories. It is as though the creatures did not make an important contribution to the life of the city. This book hopes to redress this omission and give the animals their voice, showing the role they played in shaping the economic, social and cultural history of London.

The more obvious visual reminders of Londons past animal inhabitants are the animal-related street names that bear testimony to those parts of the city that have long-held animal associations. A short list includes Bear Gardens, SEI; Bird Street, WI; Birdcage Walk, SWI; Bulls Gardens, SW3; Cowcross Street, EC1; Duck Lane, W1; Falcon Court, EC4; Hounds-ditch, EC3; Nightingale Walk, SW4; Poultry, EC2; Puma Court, EI; Swan Lane, EC4; and Whalebone Court, EC2. There are also animal sculptures littering London, such as the statue of a tiger and young boy at Tobacco Dock in Wapping, which depicts an escapee tiger from Jamrachs Exotic Animal Depository. The two stone mice that fight over a piece of cheese above the heads of passers-by in Philpot Lane, EC3, commemorate two workmen who fought on the roof over a missing lunch, leading to the death of one mice had been responsible. Some historic animal-related traditions are still enacted, albeit on an irregular or smaller scale, such as driving livestock across London Bridge or swan-upping on the Thames. Various plaques tell tales of the animals that lived and worked in urban environments long since swept away by new developments; and artefacts on view at the Museum of London paint vivid images of the variety and uses of the animals that lived permanently in or passed through the metropolis.

While there is still evidence today of Londons past association with animals, it is contemporary sources that reveal the most about the intimate bonds which existed between Londoners and the domestic, exotic and wild animals with which they shared the city. Accounts of these animals can be gleaned from early sources, such as the chronicles of London by William Fitzstephen (d. c. 1191) and John Stow (c. 15251605), and the diaries of Samuel Pepys (16331703) and John Evelyn (16201706). However, it seems that animals were so much a part of life in the early modern period that they were rarely mentioned unless they were causing a nuisance, being subjected to excessive cruelty or being viewed as a bad omen: in 1593 it was feared that the plague would worsen because a heron perched on top of St Peters, Cornhill, for the whole afternoon, and in 1604 the House of Commons rejected a bill after a jackdaw flew through the Chamber while it was being proposed. Meanwhile, early modern illustrations of London are rarely without the ubiquitous dog or horse gracing the street scene: a true indication of the animals presence on the streets.

It becomes easier to see animals in the nineteenth century, when an explosion of interest in their uses, welfare and lives led to writings by naturalists, social commentators, journalists, poets and animal-welfare organizations. Newspapers and journals also contained copious letters, features, and court and police reports concerning London animals. This interest stemmed from a change in attitudes towards brute creation, and subsequently campaigns were led to either rid the city of animals or improve their welfare.