ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The idea for this volume arose from a conference, The Mediterranean Re-imagined, held at Georgetown University in March 2013, under the auspices of the Georgetown University Center for Contemporary Arab Studies (CCAS) and chaired by Professor Osama Abi-Mershed, then director of CCAS. The conference was held, in part, to commemorate the work of our late colleague Faruk Tabak (19542008), in particular his magisterial The Waning of the Mediterranean, 15501870: A Geohistorical Approach (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008). All of the chapters in this volume emerged from papers delivered at this conference, although they have undergone substantial revision in the interim.

I would like to thank Osama for encouraging us to rethink the Mediterranean from the southern shores. A number of individuals from the CCAS staff assisted with the planning and running of the conference, including, in particular, Marina Krekorian and Elisabeth Sexton. Vicki Valosik from CCAS also provided valuable assistance in the early stages of the editing.

We benefited from the generosity of colleagues, who devoted precious time and attention to reviewing the manuscript and offered many helpful suggestions that greatly improved the coherence and analytical reach of the volume. I am truly indebted to them. Ilham Khuri-Makdisi and Konstantina Zanou read the entire manuscript and drew on their extensive knowledge of the history of the Mediterranean to guide us in our revisions. Sharif Elmusa gave the introduction a close reading and provided valuable guidance on the relevant literature of space and place.

Niels Hooper, from the University of California Press, supported this project from the beginning and employed his editors eye in ways that greatly enhanced the substance and the look of the book. Robin Manley and Kate Hoffman, also from the press, gave critical attention and assistance during the production process and in the preparation of the final manuscript. Ann Donahue was a superb copyeditor, whose broad knowledge, high standards, and attention to detail whipped the book into its final and, I hope you will agree, very fine shape.

I want to thank, last but not least, my colleagues who contributed chapters to this book. It is an honor for me to have edited a volume that contains the work of scholars I so admire. And the long years of correspondence with contributors, during which I dunned them repeatedly for one thing or another, were very pleasant ones thanks to the graciousness and collegiality of all.

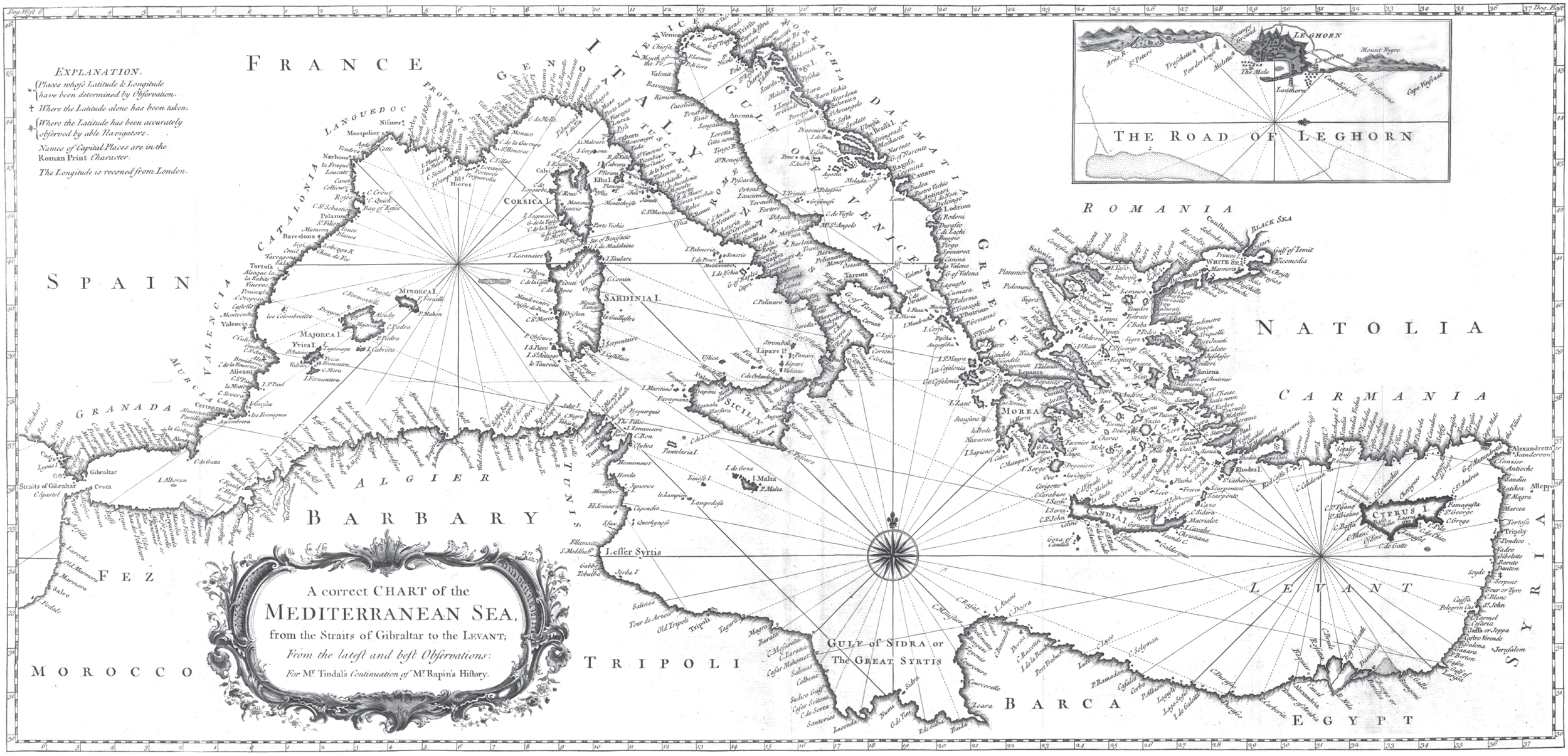

Richard William Seale, chart of the Mediterranean Sea, 1745. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Introduction

Judith E. Tucker

THINKING ABOUT THE MEDITERRANEAN

What is the Mediterranean? What are its borders, its defining characteristics? Is it a space of connection or an arena of conflict? Does it make sense as a unit of historical analysis? What forces of nature or politics or culture or economics have made the Mediterranean, and how long have they endured, or how long will they endure? How can we most productively think about the Mediterranean as a place? And, most germane to this collection, what happens when we rethink the Mediterranean from its southern or eastern shores? These questions and tensions linger in the field of Mediterranean studies, despite its embrace of the general concept of coherence.

At the outset, there is the issue of geography. John Agnew, in his essay on space and place, draws our attention to the different ways of thinking about places: as nodes in space that are acted on by external economic, social, or physical processes, on the one hand, or as milieus that play a role in shaping these processes, on the otheror, as he terms it, a geometric conception of place as a mere part of space, as opposed to place as a distinctive coming together in space. One of the best illustrations of these different ways of thinking about place, for Agnew, comes directly out of the study of the Mediterranean:

If the classic work of Fernand Braudel (1949) tends to view the Mediterranean over the long term as a grand space or spatial crossroads in exchange, trade, diffusion and connectivity between a set of grand source areas to the south, north and east, the recent revisionist account of Peregrine Horden and Nicholas Purcell (2000) views the Mediterranean region as a congeries of micro-ecologies or places separated by distinctive agricultural and social practices in which connectivity and mobility

The difference between Braudels vision of the Mediterranean as a watery space of economic and cultural connections, forged by forces emanating from an evolving world economic system, and Horden and Purcells vision of the Mediterranean as a site of multiple distinct places linked by mutual needs is more than a matter of emphasis. Braudel asserts a claim to physical Mediterranean unity on the basis of shared environment and climate, but his work pivots in the main around the Mediterranean as a human unit of collective destinies arising from the movement of peoples and goods on the sea, as a result of the economics of trade and the politics of empire in the early modern period. It was these seaborne movements in time and space that produced striking similarities and overlaps in patterns of civilization and conflict.