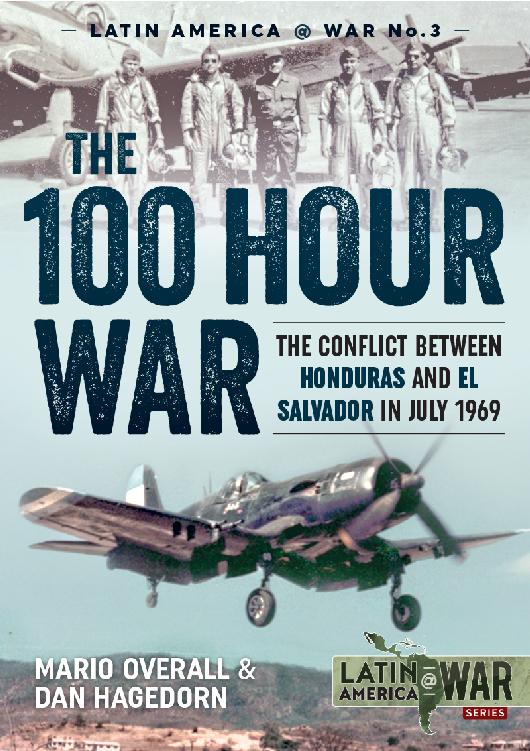

The 100 Hour War

Dan Hagedorn

Helion & Company Limited

26 Willow Road

Solihull

West Midlands

B91 1UE

England

Tel. 0121 705 3393

Fax 0121 711 4075

email:

website: www.helion.co.uk

Twitter: @helionbooks

Visit our blog http://blog.helion.co.uk

Published by Helion & Company 2017

Designed and typeset by Farr out

Publications, Wokingham, Berkshire

Cover designed by Paul Hewitt, Battlefield

Design (www.battlefield-design.co.uk)

Text Mario Overall & Dan Hagedorn 2016

Illustrations as individually credited

Color profiles drawn by Tom Cooper

Helion & Company Limited 2016

Maps drawn by George Anderson Helion

& Company Limited 2016

ISBN 978-1-911096-50-4

eISBN 978-1-911096-50-4

Mobi ISBN 978-1-913118-19-8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication

Data

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this

publication may be reproduced, stored,

manipulated in any retrieval system, or

transmitted in any mechanical, electronic

form or by any other means, without the

prior written authority of the publishers,

except for short extracts in media

reviews. Any person who engages in any

unauthorised activity in relation to this

publication shall be liable to criminal

prosecution and claims for civil and criminal

damages.

For details of other military history titles

published by Helion & Company Limited

contact the above address, or visit our

website: http://www.helion.co.uk

We always welcome receiving book

proposals from prospective authors working

in military history.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I recall vividly that hot Monday morning, July 14, 1969.

I had just returned from a mission to Ecuador and was preparing an After-Action Report when the TWX printer started chattering in the neighboring office, which by then was at Fort Kobbe in the former Panama Canal Zone.

When my boss tore off the five-page message, I was astonished to read that El Salvador had launched hostilities against neighboring Honduras.

Details were still scant, and even the staff at the U.S. Embassy in San Salvador expressed surprise early-on.

Later that morning, while glancing out the window, I saw an FAS Douglas C-47 on final into neighboring Howard Air Force Base, and drove over to the transient ramp to see what was going on. Shortly, a small convoy of blue USAF trucks and buses moved out onto the ramp and about a dozen assorted military personnel hastily boarded the C-47. A driver told me they were Salvadoran students who had been in various courses at the Inter-American Air Forces Academy at Albrook AFB and the U.S. Army School of the Americas at Fort Davis, being rushed home in the heat of the moment. The C-47, FAS-103, immediately fired-up and departed westward.

Most observers of the so-called 100-Hour War probably dont realize that the conflict of 1969, in reality, still remains active after more than 40 years. Despite a formal peace agreement, not signed until October 30, 1980. and a decision handed down by the International Court of justice as well as various rulings by the OAS, the root causes persist to this day.

Fast forward to the late 1990s. Our youngest son, Joey, had just completed a two-year stint with the Peace Corps in El Salvador, and had become engaged to a beautiful young lady of the capital. They married, and we sponsored her for U.S. citizenship. During many subsequent conversations, she provided me with a very intimate, second-hand account of the 1969 conflict from the perspective of her parents, average citizens, which was illuminating but, perhaps not surprisingly, extremely ethnocentric.

And so, with those personal experiences in mind, and my dear friend and colleague Mario Overall in agreement that it was time, we decided to make a fresh attempt at sorting out the seemingly inevitable maze of myths, half-truths and gross exaggerations that have gained a life of their own during the intervening years. We appreciate our publisher agreeing to entertain this study.

There remain many aspects that we wish dearly that we understood more clearly, but which, in the complete absence of concrete evidence, may remain the stuff of outrageous claims and counter-claims forever. That seems to be the way of even brief and obscure human conflicts.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of this sad episode remains that it settled nothing. The political power of the military in both nations was reinforced; the social situation in El Salvador worsened and, perhaps inevitably, the extremely unfortunate 10-year Salvadoran Civil War followed.

Our focus, as will be seen, has been on the aviation aspects of the war, which, in spite of everything, remain historically significant for many reasons. When all is said and done, it was the last conflict in which propeller-driven combat aircraft engaged in air-to-air warfare, the likes of which we shall almost certainly never see again.

Dan Hagedorn

Maple Valley

April 2017

A WAR BY ANY OTHER NAME

T here were simply way too many newsworthy events going on in the world during the second week of July 1969, such as the upcoming launching of the Apollo 11 mission to the moon and the first withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam. The overworked media certainly didnt need another war to cover, and much less if it was taking place in some forgotten corner of the planet. But it happened: While the world was looking the other way, the Central American nations of Honduras and El Salvador crossed sabres in a short but intense conflict that would shape the politics of the region for years to come.

With little understanding of its true causes, and pressed to come up with a catchy headline, the English-spoken newspapers began calling it The Soccer War, because the outbreak of hostilities had coincided with the elimination rounds for the 1970 Jules Rimet soccer World Cup, in which the warring countries were participating. According to the media, Salvadorans and Hondurans had clashed due to an out-ofhand sports passion, stereotypical of the hotheaded Latinos.

In any case, the derogatory term coined by the newspapers and the mistaken notion about the conflict they spread back in the day, which has been repeated endlessly by different historical sources, has only served to denigrate the inhabitants of the two countries involved. Far from being moved by simple worldly passions, a supposed blood lust or an insensate love for war, Hondurans and Salvadorans ended up facing each other due to serious political and economic problems that had their roots in the early twentieth century and not in a soccer stadium.

In order to understand the true cause of the 100 Hour War, as the Hondurans knew it, or The War of Legitimate Defence, as the Salvadorans called it, we must go back in time, to the late 1800s, when the US began exerting a strong political and economic influence over the Central American nations. That influence had allowed the United Fruit Company - UFCO and its rival, the Standard Fruit Company, to establish enormous banana plantations in the region, but most prominently in the Caribbean coast of Honduras, where both companies had also built ports and ancillary installations, besides taking over the countrys communication and transportation businesses.