The Real Fake

POLIS: Fordham Series in Urban Studies

Edited by Daniel J. Monti, Saint Louis University

POLIS will address the questions of what makes a good community and how urban dwellers succeed and fail to live up to the idea that people from various backgrounds and levels of society can live together effectively, if not always congenially. The series is the province of no single discipline; we are searching for authors in fields as diverse as American studies, anthropology, history, political science, sociology, and urban studies who can write for both academic and informed lay audiences. Our objective is to celebrate and critically assess the customary ways in which urbanites make the world corrigible for themselves and the other kinds of people with whom they come into contact every day.

To this end, we will publish both book-length manuscripts and a series of digital shorts (e-books) focusing on case studies of groups, locales, and events that provide clues as to how urban people accomplish this delicate and exciting task. We expect to publish one or two books every year but a larger number of digital shorts. The digital shorts will be 20,000 words or fewer and have a strong narrative voice.

Series Advisory Board:

Michael Ian Borer, University of NevadaLas Vegas

Japonica Brown-Saracino, Boston University

Michael Goodman, Public Policy Center at UMass Dartmouth

R. Scott Hanson, The University of Pennsylvania

Annika Hinze, Fordham University

Elaine Lewinnek, California State UniversityFullerton

Ben Looker, Saint Louis University

Ali Modarres, University of WashingtonTacoma

Bruce ONeil, Saint Louis University

Copyright 2018 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018947114

Welcome to Thames Town. Taste authentic British style of small town. Enjoy sunlight, enjoy nature, enjoy your life & holiday. Dreaming of Britain, Live in Thames Town.

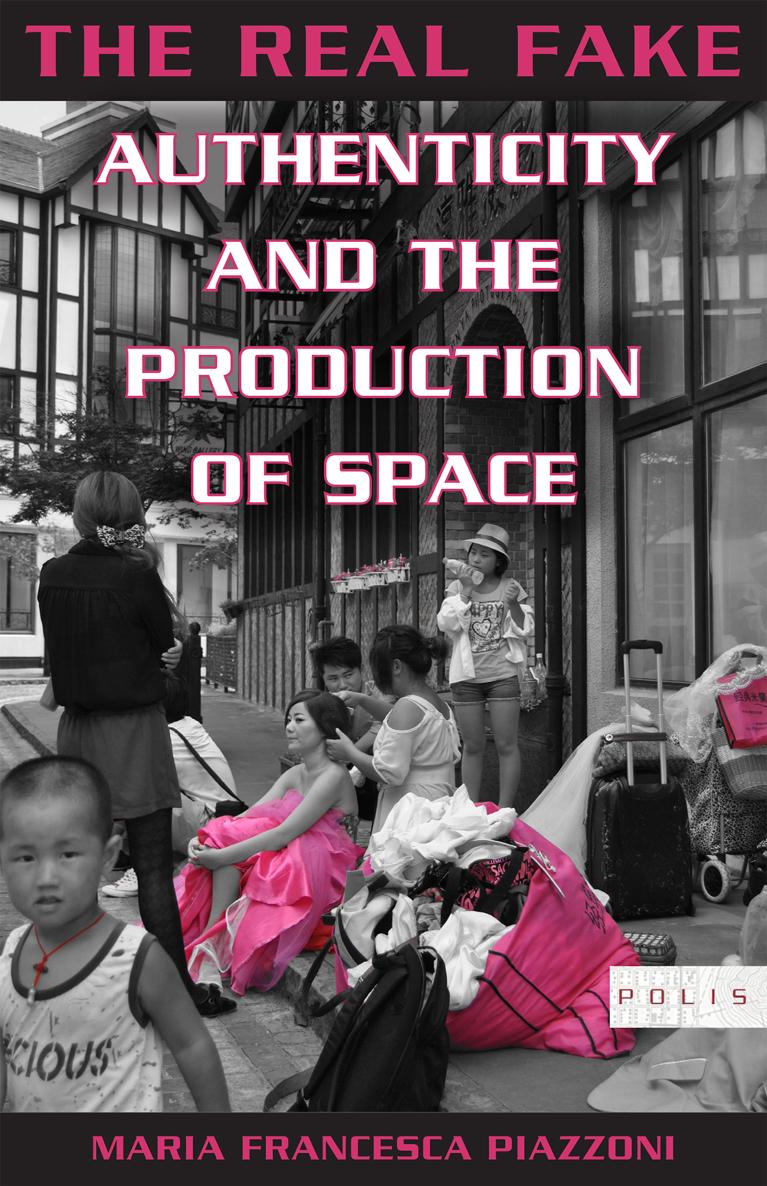

This greeting, on a sign hanging from a medieval facade, welcomes visitors to a charming English village. Everything in Thames Town is quintessentially English, from the Gothic church to the Tudor-and Victorian-style buildings. The cobblestone streets, red phone boxes, and statues of Churchill and Lady Diana offer visitors England at its best. Only one detail complicates the picture: Thames Town is in China. Located in Songjiang New Town, outside of Shanghai, Thames Town is a British-themed village built a decade ago as part of Shanghais One City, Nine Towns city plan. The plan proposed a polycentric growth model with ten new urban centers, each themed after a European country.

Designed by Atkins, a British consultancy group, and completed in 2006, Thames Town extends over one square kilometer (less than half a mile) and is enclosed within an artificial lake and network of canals. The open-access, pedestrian downtown includes a mixed-use center and residential compounds with five-to-six-story housing. Six gated residential communities surround the downtown area: Hampton Garden, Rowland Heights, Nottingham Garden, Leeds Garden, Windsor Island, and Kensington Garden, the last of which is the only gated area with terrace houses instead of single villas.

Thames Town is many places at once: a successful tourist destination, an affluent residential cluster, a city of migrantsand a ghost town. The downtown area is an important center of the Shanghai prewedding photography industry. Professional photographers capture dozens of engaged couples in a standardized sequence of posesthe romantic proposal, the candid smile, and the happily-ever-after ending. The pictures will be exhibited the day of the wedding, displaying bride and groom in a variety of matching outfitsthe fairy-tale prince and princess, Maos Red Guards, American newlyweds. The engaged couples have become an attraction in their own right, to the point that tourists visit the village to enjoy the extravagant styles of future brides and grooms.

But Thames Town is also a spectral Potemkin village that houses less than a quarter of the ten thousand people it was planned for. Occupancy remains low because most owners had no intention of living there and only purchased properties as a form of investmentreal estate values tripled between 2006 and 2012. While the gated communities are about half-full, the condominiums downtown remain semiabandoned. The open windows, hanging laundry, and parked scooters that one sees in these downtown residential areas belong almost exclusively to squatting migrant workers. Employed in the local construction business, these migrants occupy the vacant units downtown. While the residents object to the presence of the migrants outside of work hours within the gated communities, they tolerate the workers in the less iconic downtown areas.

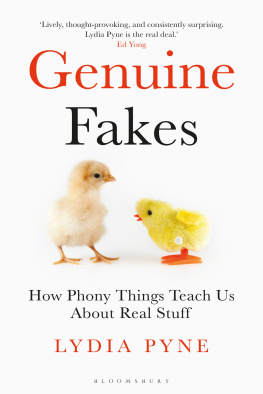

As an Italian architect trained in historic preservation, I was taught to reject the replication of ancient buildings. Mainstream preservation and design theories tell us that the authentic dimension of heritage is neither negotiable nor reproducible. What I understood, once I approached Thames Town, is that those conversations do not do justice to the nuances and complexities of places like that village. The language of real and fake fails to capture the ways the Britishness of Thames Town triggers the enthusiasm of its users, who both enjoy and construct its atmosphere in spontaneous and unexpected ways. It is the uses people make of it and the sentiments they feel that transform Thames Town into a unique place in space and time. On the one hand, this village typifies the surreal, exclusionary, and controlling aspects that scholars have long associated with themed settings. On the other hand, the Chinese residents and tourists create their own Thames Towns for themselves, genuinely and consciously enjoying the synthetic historicity.

I realized that in order to understand this Chinese-English pastiche, I had to suspend judgment on what was real and what was fake, a distinction that was the inheritance of my own cultural lens. Rather, I needed to look at how the users ideas of real and fake concretize in their understanding of the authentic and at how this understanding affects their everyday habits and uses of spaces.

In The Real Fake, I will argue that the notion of authenticity underlies the physical and social production of space. This becomes apparent in Thames Town, where the themed atmosphere influences the personal and spatial relationships among and within each group of usersthe engaged couples, the residents, the tourists, the guards, and the migrant workers. These different groups produce the spaces of Thames Town by understanding, exploiting, and complicating ideas of the authentic British atmosphere. The Western appearance of the built environment triggers the enthusiasm of the residents and visitors, who willingly modify their behaviors to enhance their own experience of the British atmosphere. At the same time, the sets of aesthetic and moral codes that residents associate with the English theme marginalize those who do not look like they belong or act appropriately.