Copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Farrell, Justin, 1984

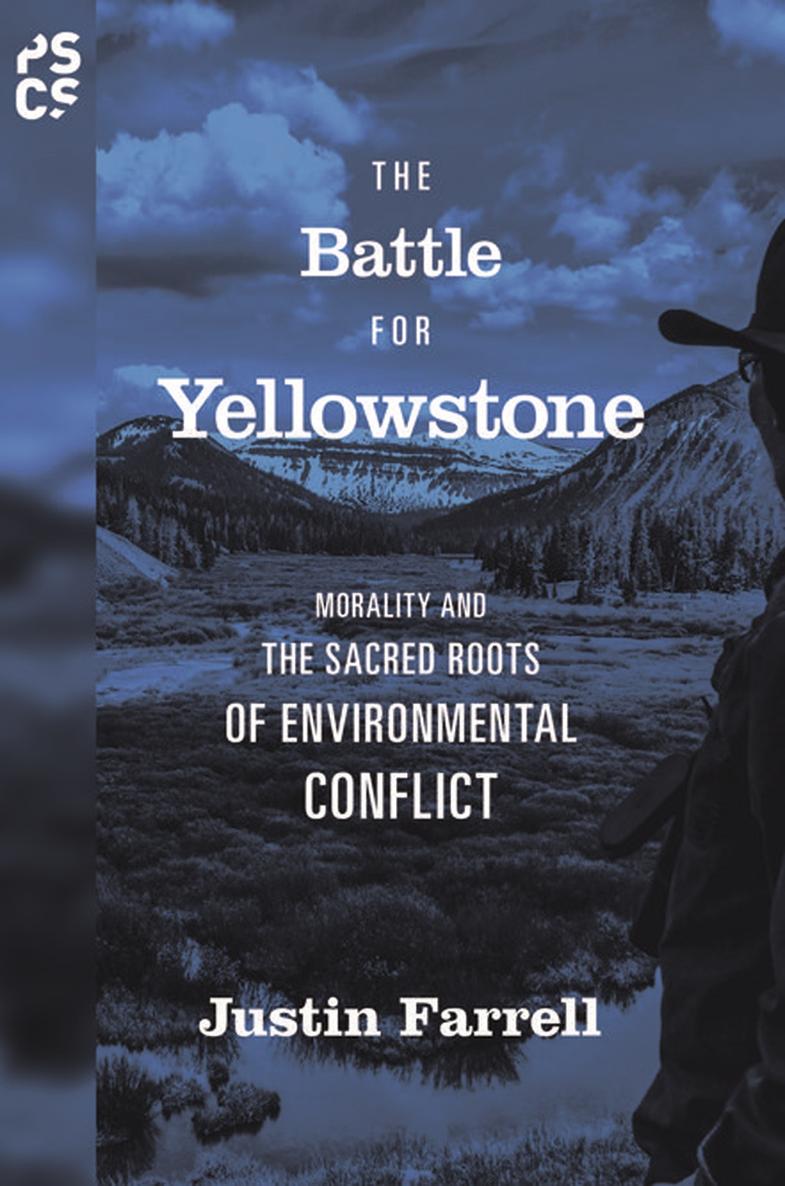

The Battle for Yellowstone : morality and the sacred roots of environmental conflict / Justin Farrell.

pages cm. (Princeton studies in cultural sociology)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-16434-2 (hardcover : alkaline paper) 1. EnvironmentalismMoral and ethical aspectsYellowstone National Park. 2. Environmental ethicsYellowstone National Park. 3. Environmental policyYellowstone National Park. 4. Yellowstone National ParkEnvironmental conditions. 5. Social conflictWest (U.S.) 6. EnvironmentalismMoral and ethical aspectsWest (U.S.) 7. Environmental ethicsWest (U.S.) 8. Environmental policyWest (U.S.) 9. West (U.S.)Environmental conditions. 10. West (U.S.)Social conditions. I. Title.

GE198.Y45F37 2015

333.7830978752dc23

2014046237

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro and Clarendon

Printed on acid-free paper.

Typeset by S R Nova Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, India

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

One of my most vivid childhood memories of the Yellowstone area was watching one summerwith my late brother Joshuaas a resort company built a small hotel next to my grandfathers aged cabin. My curiosity about the deeper meaning of this relatively minor construction project would stay with me for many years. As time passed, and with each summer spent in the area, it seemed that while so much within Yellowstone National Park stayed the same, so much just outside its borders changed. As part of an extended family deeply attached to this area, I listened over the years as relatives lamented these changes brought on by expanding tourism and land development, while at the same timeand somewhat paradoxicallyopposing government interference or increased environmental regulation aimed to slow the very changes they bemoaned. At its most basic level, this book is my own attempt to reconcile these family experiences with the cultural, moral, and political puzzles that came in their wake.

Of course, the name printed on the front of this book obscures the fact that this is the product of countless people. I am indebted to many women and men who graciously guided me on my academic journey. My earliest experiences in Princeton working for Robert Wuthnow conducting interviews with farmers in the rural midwest opened my eyes to the study of culture, and with his help, I applied to graduate programs in sociology. Since that time, Bob has been a steady and invaluable resource, including reading and commenting on a full draft of the manuscript.

I owe my biggest debt of gratitude to Chris Smith and Omar Lizardo. Chriss direct and incisive advice kept me grounded and on track as I struggled to bring the Yellowstone conflict into conversation with sociology of culture, environment, morality, and religion. Omar gave me the confidence to follow my instincts, to think outside of the box, even in the face of disciplinary norms and boundaries. Fortunately, too, Omars guidance happened most often with the assistance of a good microbrew. I know that at times I pushed the limits of the idiom not all who wander are lost, but nevertheless, Chris especially continued to believe in the project during its most difficult seasons. With a spirit of patience, he invested in the idea by asking difficult questions, giving blunt feedback, and pushing me to continually make the project better. Indeed, Chris and Omars critical eyes and valuable insight were matched only by their consistent generosity. I am also indebted to Kraig Beyerlein, for our early morning conversations that kept my eye on the methodological ball, especially in the early stages as I planned my research strategy. Rory McVeigh influenced the project more than he may realize, with his continual push for me to focus on the broader structures of moral culture. In addition to commenting on various stages of the project, Jessica Collett and Terence McDonnell were a constant source of positive encouragement. My fellow graduate students Daniel Escher, Peter Barwis, and David Everson helped in many different ways. I am thankful for their friendship. Last, I want to thank Eric Schwartz, Meagan Levinson, Ryan Mulligan, and Leslie Grundfest at Princeton University Press for their support and expertise during the publishing process. Additionally, I am indebted to the series editors, Paul DiMaggio, Michle Lamont, Robert Wuthnow, and Viviana Zelizer, for their initial enthusiasm about the project.

I am extraordinarily grateful to the people in the Greater Yellowstone area who let me into their lives. From the miners, farmers, and ranchers, to the new-west transplants, anti-wolf activists, and conservationists, I hope that in what follows I have rewarded your trust and faithfully told your stories in all of their fascinating complexity.

Support for research and writing of the book was provided by a three-year STAR Graduate Fellowship from the Environmental Protection Agency, as well as various grants and fellowships from the graduate school at Notre Dame, the Center for the Study of Religion and Society at Notre Dame, the Louisville Institute, the National Science Foundation, the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, and the Religious Research Association. After collecting the data, I wrote a good portion of the manuscript at Blue Line Coffee in Omaha, Nebraska, and am grateful to Chris and the baristas for pouring out such a rich source of community.

As I reflect upon the years that it took me to write this book, it becomes harder and harder to separate the manuscript from the priceless memories spent with family during its various stages. In reading the various data, sections, and chapters, I see the life-sustaining love during holiday celebrations, family dinners, spirited political discussions, Frisbee with sweet-boy-Norman, festive parties, tailgate BBQs, and the like. The Renshaw clan were always the first to celebrate even the smallest achievement, and the exuberance with which they pour out their love still astounds me to this day. My brother Jordan offered constant encouragement, in addition to his own academic expertise, reading and insightfully commenting on every chapter. My parents, Mike and JoAnn, my biggest fans, have been by my side since I decided on a life in academics. They have been especially supportive of this project and, with their knowledge of the Yellowstone area, have been indispensable discussion partners. As a first-generation college student, my foray into the academic world was as new to them as it was to me, but that did not stop them from offering their unconditional support, and even participating with me in this new life of learning. It is readily apparent how proud they are of me, but as I grow older, I find myself reflecting on how proud I am of them.