This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

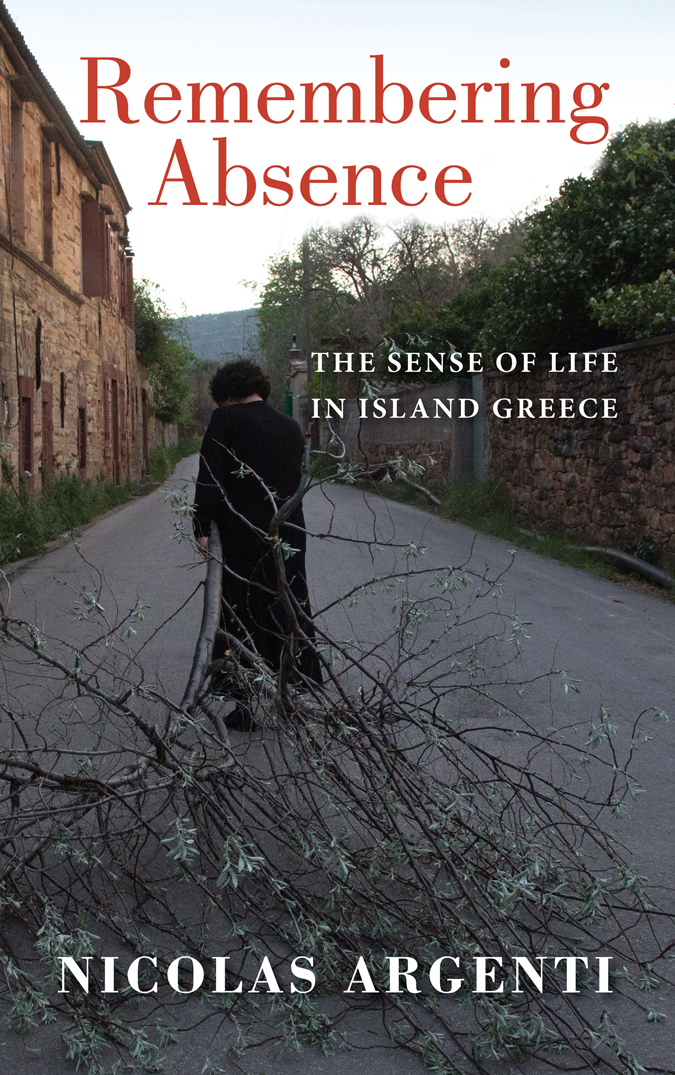

2019 by Nicolas Argenti

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-253-04065-7 (hdbk.)

ISBN 978-0-253-04066-4 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-253-04067-1 (web PDF)

1 2 3 4 5 24 23 22 21 20 19

In memoriam

Barbara Argenti (19322012)

No more of the old security.

It was sea and islands now.

C. S. LEWIS, SURPRISED BY JOY

and for her grandchildren,

Chiara, Quentin, Lalla Lee, Virginia, Eleanor, and Loukis

Voice of the Lord upon the waters,

There is an island.

GEORGE SEFERIS, SALAMIS IN CYPRUS, LOGBOOK III

Peu de gens devineront combien il a fallu tre triste pour entreprendre de ressusciter Carthage! Cest l une Thbade o le dgot de la vie moderne ma pouss.

GUSTAVE FLAUBERT, LETTER TO ERNEST FEYDEAU

Sit still, and hear the last of our sea sorrow.

Shakespeare,The Tempest

T HIS WORK SETS OUT THE FINDINGS OF RESEARCH carried out over the course of a series of trips to the Aegean island of Chios between 2010 and 2015. Originally envisaged as an inquiry into collective memories of the massacres of 1822 that divided the island into an emigrant diaspora and a local population, the project was designed to examine that fork in the islands fate from both perspectives. This volume focuses for the most part on the results of my research with the latter of these two groups. As often happens in the course of ethnographic research, the project was overtaken by events; in this case, the sovereign debt crisis took hold of the Greek economy and people faced life-changing transformations in their standard of living, governance, future prospects, and identity. Having been conceived in the framework and language of memory studies, the research thus stumbled into a hybrid landscape of resurgent memories, current concerns, and anxieties about the future. Because these temporal domains were inevitably presented by those to whom I spoke not as distinct categories but as inextricably intertwined fields of experience, the research took me beyond the memory paradigm within which my work had heretofore found its footing, forcing me to grapple with more fundamental questions about the nature and experience of time itself. Exceptional as the current circumstances facing Greece and southern Europe may now seem, this work does not seek to present a society in crisis or to delineate an ethnography of exception but to examine how the warp and weft of past, present, and future have been part and parcel of an island communitys experience on a long-standing basis. Far from constituting a symptom of crisis, this imbricated temporality represents a means of placing the present in a wider temporal context, suggesting a form of simultaneity that has been a feature of Aegean and wider Mediterranean culture for centuries.

A study of the forced movements of people across Anatolia and the Aegean will inevitably raise questions regarding contemporary events, and the reader may wonder how a description of the island of Chiosespecially one that focuses on the descendants of people who were cast on its shores or banished from them in the ceaseless revolution of the centuriescould fail to take account of the influx of refugees now fleeing the latest conflict in the Middle East, those who congregate on the Erythrean Peninsula of Turkeys Aegean coast before daily setting out in small and perilously overcrowded boats and attempting to cross that sea of sorrow in the hope of finding asylum in this southern outpost of the European Union. So many times in the past have people been driven across these narrow straits that the islands of the Aegean are nothing if not the result of the mass movement of people across space and time, collectively presenting a fulcrum in the contact between Eastern and Western cultures and societies. What ethnography, then, would ignore the present crisis in seeking to depict a contemporary society born of just such crises? What monograph would describe an island of immigrants and emigrants, exiles and refugees, without accounting for the new diaspora washing ashore as I write these words?

The question can be answered empirically and epistemologically. Practically speaking, this research was conducted before the war in Syria had begun to send significant numbers of that nations citizens across the border to Turkey and thence into the Aegean. During the conduct of this research, crossings regularly occurred of refugees to Chios, and they are mentioned in the chapters that follow insofar as they concerned and affected local people, but the large-scale humanitarian crisis associated with the current conflict had not yet begun. This monograph therefore covers a period anterior to these events.

The epistemological dimension of the question raises issues central to this book. While the current influx of people to Chios presents evident superficial continuities with critical events in the history of the island, it is also different in important ways: for one thing, the last mass movement of people to Chios was of Greek-speaking Orthodox coreligionists forced to leave Asia Minor under the terms of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. Many of them settled permanently on the island, and the vast majority of them remained in Greece. The current influx of people, mostly Arab-speaking Syrian Muslims, bear little cultural or historical affinity with contemporary local Chiots, are not the product of a legally ratified movement of people, and do not intend to stay in Greece, let alone in Chios. Moreover, their indeterminate legal status precludes them from integrating in local society, from which they are by and large physically separated by enclosure in makeshift camps. Both in terms of local perception and of the migrants own experience, therefore, the migrants are presently in Chios, but they are not part of the present of Chiot society.

The tragedy of this displacement not only in space but also from the present is what constitutes the belatedness of crisis: It may be that, in time, some members of this refugee movement will settle in Chios or on neighboring islands and become part of local society. It may be that Chiots will one day incorporate memories of the current crisis into their sense of identity as they have past crises, and it may be that the refugees, going on to form diasporic societies in other parts of the world or in a future reconstituted state of Syria, will incorporate their flight and their passage through the Aegean into their transgenerational collective memories. Because such futures have not yet come to be, and because the present of the current crisis has as yet no past and no place in collective memory, it is not meaningfully part of contemporary Chiot society, and how it will one day come to inform local culture is as yet undetermined. So we can say, with Michel de Certeau, that only the passing of an epoch allows us to express what had made it live, as if it had had to die to become a book ([1980] 1990, 28687, my trans.).

![Sherry Marker - Frommers Greek Islands [2010]](/uploads/posts/book/235532/thumbs/sherry-marker-frommer-s-greek-islands-2010.jpg)