Mastodons to Mississippians

TRUTHS, LIES, AND HISTORIES OF NASHVILLE

Betsy T. Phillips, series editor

As a lead-up to Nashvilles 250th anniversary in 2029, Vanderbilt University Press is publishing an ambitious new series consisting of twenty-five small volumes designed to bridge the gap between what scholars and experts know about the city and what the public thinks it knows. These are the stories that have never been told, the truths behind the oft-told tales, the things that keep us in love with the city, and the parts of the past that have broken our hearts, with a priority on traditionally underrepresented perspectives and untold stories.

MASTODONS TO MISSISSIPPIANS

ADVENTURES IN

NASHVILLES DEEP PAST

AARON DETER-WOLF & TANYA M. PERES

VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY PRESS

Nashville, Tennessee

Copyright 2021 Vanderbilt University Press

All rights reserved

First printing 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Deter-Wolf, Aaron, 1976 author. | Peres, Tanya M., author.

Title: Mastodons to Mississippians : adventures in Nashvilles deep past / Aaron Deter-Wolf and Tanya M. Peres.

Description: Nashville : Vanderbilt University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021009786 (print) | LCCN 2021009787 (ebook) | ISBN 9780826502155 (paperback) | ISBN 9780826502162 (epub) | ISBN 9780826502179 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Nashville (Tenn.)Antiquities. | Mississippian cultureTennesseeNashville. | MoundsTennesseeNashville. | Indians of North AmericaTennesseeNashvilleAntiquities. | Paleo-IndiansTennesseeNashville. | ArchaeologyTennesseeNashville. | PaleontologyTennesseeNashville.

Classification: LCC E99.M6815 D48 2021 (print) | LCC E99.M6815 (ebook) | DDC 976.8/5501dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021009786

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021009787

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our many colleagues and the members of the Nashville community who spoke with us about their research, experiences, and memories of Nashville archaeology. Alan Brown, Brian Butler, John Broster, Larisa DeSantis, John Dowd, Nick Fielder, Shannon Hodge, Don Hubbs, David Sims, Kevin Smith, Jesse Tune, David Wilson, Ron Zurawski, and others graciously shared their expertise during uncertain times. Mauricio Antn, David Dye, Lacey Fleming, Les Leverett, Nol Lorson, Robert Sharp, Debbie Shaw, and the staff of the Tennessee State Museum all contributed or assisted with images. We also wish to thank Tennessee state archaeologist (now retired) Mike Moore, for over a decade of support, encouragement, and steady guidance.

We offer acknowledgment to the Native American communities and individuals who for millennia have made their homes in the Cumberland River valley of Middle Tennessee, and whose ancestral sites have been displaced by historical and modern development. Through careful and considerate examination of the archaeological record we hope to increase understanding and respect for these cultures, their accomplishments, and their legacies.

CHAPTER 1

Making Sense of Nashvilles Deep Past

In 1845 workers digging a well on William Shumates farm, located seven miles south of Franklin, uncovered a giant skeleton. Around fifty feet below the surface the well shaft encountered a fissure in the limestone bedrock, at the base of which lay a collection of massive bones belonging to an American mastodon. This was not the first mastodon discovery in America, or even in Tennessee. By that time, remains of Mammut americanum, an extinct species of ice age elephant, had been recovered from various locations throughout the eastern United States for more than a century. Those skeletons were enthusiastically reported on in newspapers and historical texts, and displayed with great fanfare in natural history museums of the era.

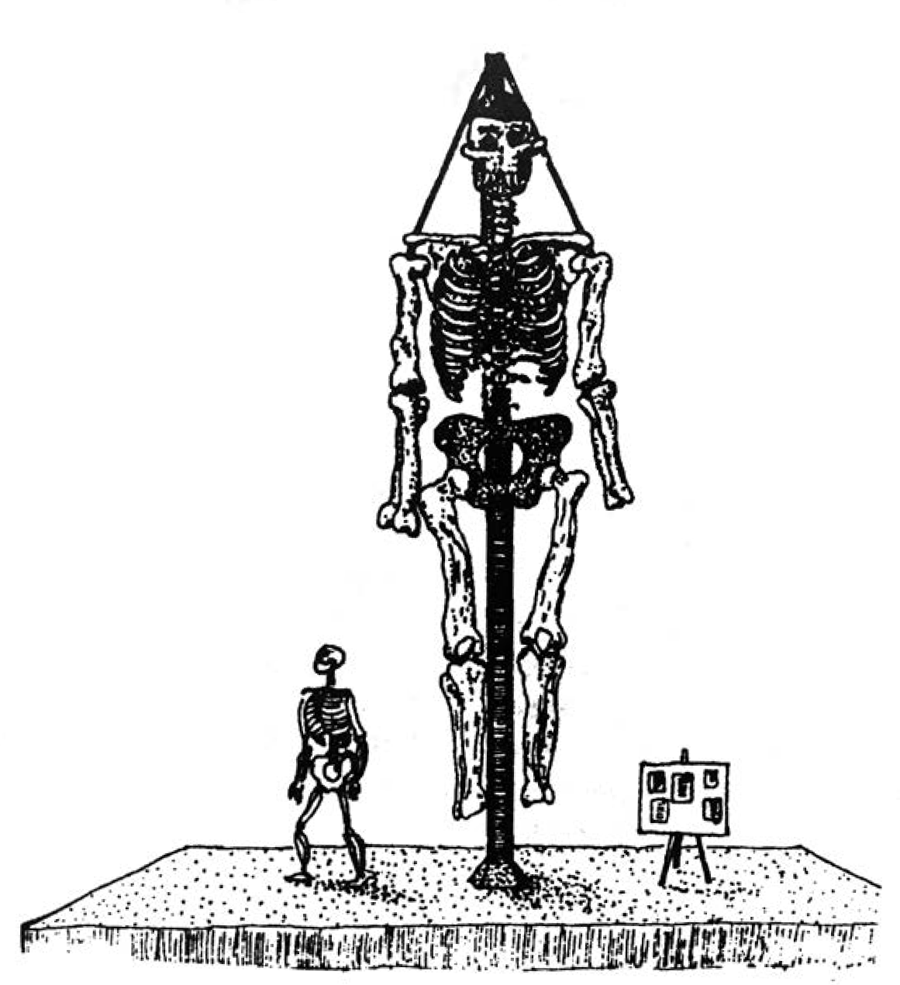

Like many fossil skeletons of the era, the Shumate Mastodon was displayed for the publics viewing pleasure. There was, however, a twist: mounted upright on two legs and improved by the addition of wooden pieces to replace missing portions of the skull and pelvis, to popular demand, the price of admission increased to thirty cents, though with a 50 percent discount for servants and children. From Nashville, the exhibit embarked on a tour to New Orleans, where the fraud was quickly recognized by a medical professor. The skeleton disappeared from public view, although not before convincing thousands of visitors that the Nashville area was once home to an ancient race of giant humans.

FIGURE 1.1. Sketch of Shumates grand Monster Tennessean. When exhibited in Nashville in December 1845, the mastodon remains were mounted upright beside an articulated human skeleton for scale. After James X. Corgan and Emmanuel Breitburg, Tennessees Prehistoric Vertebrates, Tennessee Division of Geology Bulletin 84 (Nashville: State of Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, 1996), fig. 1.

It is not unusual for those digging holes in Middle Tennessee to uncover pieces of the deep past. Historical documents from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries record what seems to be a near-continuous stream of encounters with ancient remains. Those range from accidental fossil discoveries such as the Shumate Mastodon to deliberate excavations of ancient Native American sites by antiquarian scholars from the likes of Harvards Peabody Museum. In the middle of that spectrum fell the interested public of Nashville and Middle Tennessee, some of whom spent their leisure time collecting fossils or digging up Native American sites in search of artifacts and curiosities. This trend continues today, as Nashvilles growing population and associated development expand throughout Middle Tennessee and spur both formal archaeological studies and accidental encounters with the past.

During the first decades of the twenty-first century there have been occasional, brief peaks of public interest in our citys deep past. These are typically in response to ancient Native American sites being threatened or impacted by development efforts, such as the large May Town Center project proposed for Bells Bend in 2008, or construction of the new Nashville Sounds stadium in 2014. For the most part, however, the citys ancient past has remained a mere footnote to its antebellum and more recent history.

Aside from the good work of the Tennessee State Museum and occasional roadside historical markers, the popular interpretation and treatment of ancient Nashville has been driven mainly by curiosity and imagination rather than modern science. Without the benefit of responsible, accessible sources, explanations of Nashvilles deep past have over the years included tales about lost races of giants and pygmies, various ancient Old World cultures, and the Moundbuilders, an outdated nineteenth-century term for the Native Americans who created North Americas first monumental architecture. On the other hand, sources written for schoolchildren, and those for a more general public audience, might lead us to believe that the first Europeans arrived on the banks of the Cumberland River in the late seventeenth century to find a pristine landscape, inhabited only by herds of bison and boundless nature, entirely untouched by human hands.