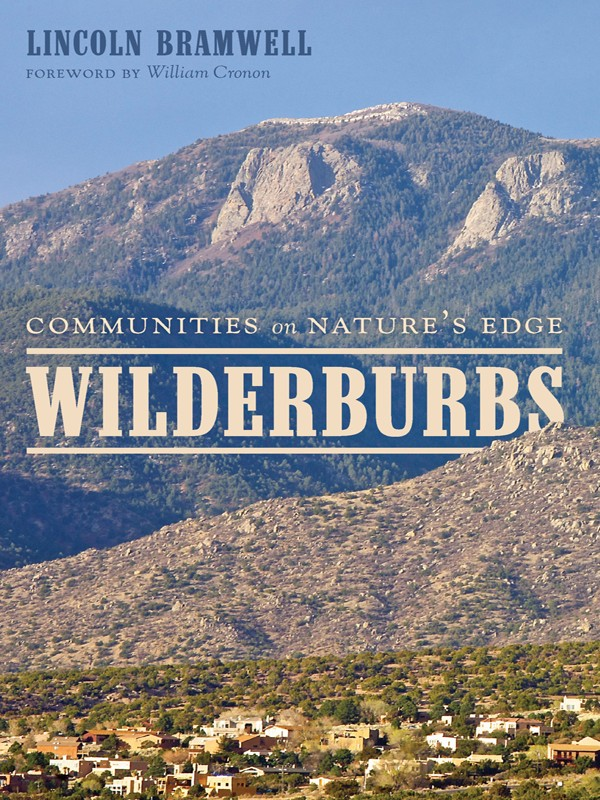

WEYERHAEUSER ENVIRONMENTAL BOOKS

William Cronon, Editor

WEYERHAEUSER ENVIRONMENTAL BOOKS explore human relationships with natural environments in all their variety and complexity. They seek to cast new light on the ways that natural systems affect human communities, the ways that people affect the environments of which they are a part, and the ways that different cultural conceptions of nature profoundly shape our sense of the world around us. A complete list of the books in the series appears at the end of this book.

Wilderburbs: Communities on Nature's Edge is published with the assistance of a grant from the Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books Endowment, established by the Weyerhaeuser Company Foundation, members of the Weyerhaeuser family, and Janet and Jack Creighton.

Portions of chapters appeared previously in Lincoln Bramwell, Wilderburbs and Rocky Mountain Development, in Country Dreams, City Schemes: Utopian Visions of the Urban West, ed. Amy Scott and Kathleen Brosnan (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2011), 88108.

2014 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Design by Thomas Eykemans

Composed in OFL Sorts Mill Goudy, typeface design by Barry Schwartz

Cartography by Barry Levely

17 16 15 14 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALO GING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Bramwell, Lincoln.

Wilderburbs : communities on nature's edge / Lincoln Bramwell.

pages cm. (Weyerhaeuser environmental books)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-295-99412-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Wildland-urban interfaceWest (U.S.) 2. SuburbsWest (U.S.) 3. Urban-rural migrationWest (U.S.) 4. Rural developmentWest (U.S.) 5. Land use, RuralWest (U.S.) I. Title.

HT352.U62W473 2014

307.760978dc23

2014006290

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-984.

ISBN 978-0-295-80558-0 (ebook)

To Christi, Lincoln, and Jackson

and to the memory of my parents

FOREWORD

Living on the Edge

WILLIAM CRONON

THE DREAM OF LIVING CLOSE TO NATURE HAS BEEN A CURIOUS FEATURE of American urban life since at least the middle decades of the nineteenth century. As growing numbers of people began migrating from country to city in the decades following the Revolution, and as cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia grew to feel ever more crowded, those who could afford to distance themselves from metropolitan environments while still enjoying the benefits increasingly sought to do so. The goal was never to live too far away, since urban elites made their fortunes in cities and desired both the cultural amenities and the opportunities for conspicuous consumption that only cities offered. But if they could get away at least some of the timeon weekends or during summer months or, best of all, each evening at the end of a long day of workthen it might be possible to have the best of both worlds: the wealth and cultural richness of the metropolis and the greenery and peaceful beauty of the country. Just so was born the romantic suburb on the edges of the great nineteenth-century cities: Alexander Jackson Davis's Llewelyn Park in New Jersey, Alexander Stewart's Garden City in New York, Frederick Law Olmsted's Riverside in Illinois, and many others. With capacious lots laid out along gently curving lanes, so that large houses could be surrounded by extensive yards adorned with grass and trees and gardens, such places offered well-to-do urbanites the chance to retreat from the city to revel in the pleasures of rural life.

The earliest romantic suburbs tended to be located along railroad lines, where only those with large reliable incomes could afford to pay the daily fares between home and workplace, let alone the expensive real estate associated with such communities. Later in the nineteenth century, less expensive light-rail networks brought Sam Bass Warner's famed streetcar suburbs into being, with smaller lots, more crowded multi-family dwellings, and less pastoral landscapes. Then, by the middle decades of the twentieth century, mass ownership of the automobile made it possible for people of more modest means to pursue the dream of living out in the country even as they earned their livelihoods with urban jobs. Unfortunately, that dream of country living more often than not eluded them. The mass-produced Levittowns of the post-World War II era, and the advent of new zoning ordinances that mandated the physical isolation of houses from schools and factories and retail stores, contributed to landscapes that by the 1960s were increasingly criticized as suburban sprawl. For critics, the automobile suburbs of the 1950s and 1960s brought not the best of city and country, but the worst: few urban amenities and nothing that plausibly passed for nature, whether pastoral or wild. Those who wanted a more persuasive experience of natural living started to look even farther out, beyond the suburbs toward the exurbs and beyond.

By the closing decades of the twentieth century, the period Lincoln Bramwell explores in his thought-provoking Wilderburbs: Communities on Nature's Edge, this long process of flight from the city had reached what seemed to be its outer limits. Bramwell traces the emergence of far-flung communities in the Rocky Mountain West, where well-to-do Americans can purchase or rent houses and condominiums with all the creature comforts of urban lifeelectricity, telecommunications, tap water, flush toilets, central heating and air-conditioningeven as the views from their picture windows frame some of the wildest landscapes in the United States. Although the isolation of such places means that few residents make a physical daily commute to the metropolitan economies where most still earn their livingsthese are mainly vacation and retirement communitiesthe advent of cell phones and high-speed Internet connections means that wilderburb residents can continue their work from afar in ways that would have been inconceivable just a few decades ago. Wilderburbs are thus a near-perfect exemplar of what Karl Marx called the annihilation of space by time, diminishing the importance of spatial isolation as the movement of physical objects and information accelerates. Never before has it been possible to live so far from the city while remaining so closely connected to it. Never before has the suburban dream been so perfectly realizedor so it might seem.

The technological and political-economic transformations that make wilderburbs possible have been operating for at least a half-century. They occur in whatever remote locations urban folks with large amounts of disposable income decide they would like to dwell in for at least part of the year. As such, one can find wilderburbsand the resort communities that are their near analogue in global tourismall over the world. But to study them on such a scale would be to run the risk of missing the finegrained local details that are among their greatest fascinations. That is why Bramwell has wisely chosen to limit himself to a handful of paradigmatic examples in the American West: Foresta, California, near Yosemite; the Burland Ranchettes, near Evergreen, Colorado; the Snyderville Basin near Park City, Utah; and the Paa-Ko Communities near Albuquerque, New Mexico. Some of these communities are relatively well known; others less so. But all share certain attributes. People travel a distance to reach them because of their special combinations of comfort and rusticity. The developers who created them did so with the intention of marketing to people willing to spend sizable amounts of money to live in the presence of wild nature. Experiencing wilderness in such places can be as simple as walking out one's back doorand returning to civilization is as easy as going back inside, through that same door. One's first visit to such communities often sets off a cascade of fantasies about what it would be like to live in them. If what one seeks are the latest incarnations of America's suburban dreams, then the four communities Bramwell has chosen to describe would be hard to beat.