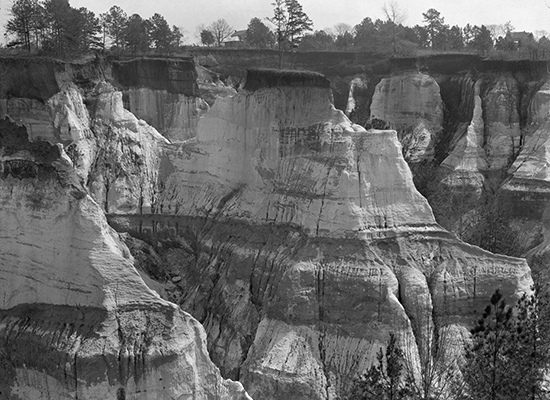

The following is a series of photographs, many attributed to and the rest almost certainly taken by the well-known New Dealera documentary photographer Arthur Rothstein, of massive gully erosion in Stewart County, Georgia. Many are scenes from what would become Providence Canyon State Park, the subject of this book. The Library of Congress holds these photographs, and many of them are titled, simply, Erosion, Stewart County, Georgia. Courtesy of the Farm Security Administration / Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

Let Us Now Praise Famous Gullies

SERIES EDITOR

James C. Giesen, Mississippi State University

ADVISORY BOARD

Judith Carney, University of CaliforniaLos Angeles

S. Max Edelson, University of Virginia

Robbie Ethridge, University of Mississippi

Ari Kelman, University of CaliforniaDavis

Shepard Krech III, Brown University

Megan Kate Nelson, www.historista.com

Tim Silver, Appalachian State University

Mart Stewart, Western Washington University

Paul S. Sutter, founding editor, University of Colorado, Boulder

Let Us Now Praise Famous Gullies

Providence Canyon and the Soils of the South

Paul S. Sutter

2015 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Set in Adobe Garamond by Graphic Composition, Inc.,

Bogart, Georgia

Printed and bound by Thomson-Shore, Inc.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Most University of Georgia Press titles are available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed in the United States of America

19 18 17 16 15 c 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN: 978-0-8203-3401-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-0-8203-4809-4 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015949031

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

CONTENTS

, by James C. Giesen

ILLUSTRATIONS

FOREWORD

Irony has long been a theme of southern history, albeit a tricky one. Historians of the region have filled many shelves with books and articles describing the places and times when historical actors were unaware of the predicaments in which they were putting themselves. They take pains to describe the ways in which southerners, from the colonial era through the twentieth century, misunderstood their world. Scholars and readers alike seem to relish that surprising moment when their characters wake to find that the world they have made is not the one that they thought they were building. Appreciating unexpected and seemingly contradictory political movements, social crusades, or economic trends is a stock and trade of traditional southern history because, to put it bluntly, southern history has been ironic. The tricky thing about irony, however, is that its lessons are rarely satisfying. Its meaning is often hard to apply to other historic events or actors. As a tool for understanding the present, irony has had a frustratingly dull edge.

What follows is a book about an ironic place, Providence Canyon, a system of beautiful, historic, cavernous erosion gullies in west Georgia. Of all the remarkable things about the canyon, the irony of its creation and preservation is one of the most important. To begin to understand it, turn back to the cover for a moment, or flip again through the plates that open the volume, and look once more at the images. The striated towers of subsoil jutting up, or falling off, from the earths surface trigger thoughts of the American West, of national parks set aside to preserve a seemingly supernatural aesthetic. But of course Providence Canyon is not the Grand Canyon. It is not an earth formation built on a millennial scale but rather the product of human work that of a few generations rather than millions of yearson soil that once existed where now there is only air. As Paul S. Sutter explains, there is irony in a park that preserves the natural results of human-induced soil erosion, but what makes this volume truly pathbreaking and important is that this irony is merely where the story begins.

In Let Us Now Praise Famous Gullies, Sutter sets out to understand how the canyon came to be, why local and state officials preserved it as a park, and how the public should think about and engage with it today. It is a story that takes us from the floor of Providence Canyon to the surrounding lands of Stewart County, Georgia, around the cotton and tobacco South, through forests and government offices, and back again to Providence Canyon. It is a history not just about farmers extracting nutrients from the soil in search of profit and the land wasting away as the result. This is a history of the understandings of southern soil itself, the emergence of a science to research soil formation and weathering, and the bureaucracies that resulted. Sutter demonstrates how farmers, local officials, geologists, politicians, and a host of others made meaning first in farmland, then in the growing gullies of Stewart County. The meaning of Providence Canyon is not something fixed by the irony of its man-made origins and natural beauty, however. In fact, as Sutter explains, the meaning of Providence Canyon has never been static. Local farmers had no interest in making the growing fissure anything more than a regional oddityin the nineteenth century they did not think much about it at all. As time passed, more and more people attempted to make something out of the gullies, to derive a lesson in the origins and existenceand yes, the ironyof Providence Canyon. Sutter reminds us as well that forgetting is itself a way to make meaning. In the final part of this book, he details the dangers of erasure, from both environmental and cultural forces, of the canyons history.