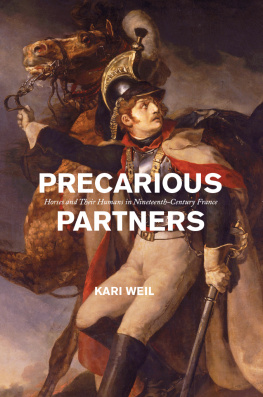

PRECARIOUS PARTNERS

ANIMAL LIVES

Jane C. Desmond, Series Editor; Barbara J. King, Associate Editor for Science; Kim Marra, Associate Editor

BOOKS IN THE SERIES

Displaying Death and Animating Life: Human-Animal Relations in Art, Science, and Everyday Life

by Jane C. Desmond

Voracious Science and Vulnerable Animals: A Primate Scientists Ethical Journey

by John P. Gluck

The Great Cat and Dog Massacre: The Real Story of World War Twos Unknown Tragedy

by Hilda Kean

Animal Intimacies: Interspecies Relatedness in Indias Central Himalayas

by Radhika Govindrajan

Minor Creatures: Persons, Animals, and the Victorian Novel

by Ivan Kreilkamp

Equestrian Cultures: Horses, Human Society, and the Discourse of Modernity

by Kristen Guest and Monica Mattfeld

PRECARIOUS PARTNERS

Horses and Their Humans in Nineteenth-Century France

KARI WEIL

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-68623-3 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-68637-0 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-68640-0 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226686400.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Weil, Kari, author.

Title: Precarious partners : horses and their humans in nineteenth-century France / Kari Weil.

Other titles: Animal lives (University of Chicago Press)

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2020. | Series: Animal lives | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019031493 | ISBN 9780226686233 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226686370 (paperback) | ISBN 9780226686400 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: HorsesFranceHistory19th century. | HorsesSocial aspectsFrance. | Human-animal relationshipsFranceHistory19th century. | Animals and civilizationFrance.

Classification: LCC SF284.F7 W45 2020 | DDC 636.10944dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019031493

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

In memory of Holly

CONTENTS

I started work on this book over twenty years ago. It grew out of research for my first book, which dealt with notions of androgyny and representations of changing or ambiguous gender in French, German, and British literary works of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I was struck by French women who were described as cross-dressing in order to work with horses and ride astridemuch to the shock of their contemporaries. Horses, I understood, offered one perspective into the massive changes in gender relations, but also in class and race relations, that were taking place during the nineteenth century. Or that was how my more established colleagues encouraged me to see the value of my research. But for me there was more in it. As a rider and lifelong lover of horses, I was also interested in them for their own sake. I wanted to understand the kinds of relations people had with horses, whether on the ground or in the saddle. I feared, however, that studying animals in this way not only was unconventional but also risked being dismissed as sentimental and unworthy of an academic. The field of animal studies did not yet exist. Its emergence and growth over the past fifteen years or so have had an enormous influence on this work, not only by making me believe in the importance and relevance of my topic, but also by bringing me to consider emerging debates about animal agency and consciousness, about the politics and ethics surrounding companion species, and about the significance of our joint bondsthen and now. Indeed, I had hoped to catch some glimpse or insight into what might have been a horses own point of view two centuries ago, but in this effort I was stymied by a dearth of source materials, by fear of my own projections, and by my ignorance of how to locate the traces of that viewpoint other than in the effects reported by a horses human.

When I first presented some of my work at an animal studies conference (not the French and comparative literature conferences I had mostly attended), another presenter, a political philosopher, asked how I could in good conscience ride horses. Isnt it comparable to slaveholding, he asked, the horses bit another kind of shackles? I understood where the question was coming from, having familiarized myself with animal abolitionist arguments, but I felt unprepared to answer. I could have said I believed some horses (not all) like being ridden and enjoy the partnership they experience with a rider. Riding is also one way we humans can get to know the personality and individuality of a particular horse (and vice versa). At the same time, a statement of Jean-Jacques Rousseaus came to mind. It is neither for slaves nor for tamed horses to reason about freedom, for they know only their broken state. The untamed steed bristles its mane, stamps the ground with its hoof, and struggles impetuously at the sight of the bit.

Sometime after that conference I put aside my horse book to pursue different and often more theoretical questions raised by my readings and collaborations in animal studies. This pursuit was aided by my move from French departments to programs that promoted more interdisciplinary study, first at the California College of Art and then at Wesleyan University. In my classes and my research for my previous book, Thinking Animals: Why Animal Studies Now?, I turned to twentieth- and twenty-first-century literature, art, and theory that zeroed in on knotty issues of animal ethics but also looked deeply into problems of language and representation and the dangers of anthropomorphism and anthropocentrism. When I returned to research on horses in nineteenth-century France, these issues presented themselves in new and often unforeseen ways, even as my focus was contained within a more specific historical and geographical context that was largely absent from Thinking Animals. Nevertheless, as I was finishing the manuscript I was surprised to find how relevant many of the issues continue to be.

To be sure, horses are no longer central to daily life as they were in the nineteenth century, but the contest over who or what they are and who and what they and their image serve continues to be waged in ways that reflect ongoing social, sexual, political, and ethical issues. Just last summer the University of Wyoming released its new marketing campaign with the slogan the world needs more cowboys. Faculty protested because of the cowboys white, macho image, and Native Americans on campus joined in, saying that for them cowboys holds a negative connotation. Those who favored removal saw the statue as a monument to white supremacy. Those who opposed removal accused the other side of wanting to erase historya history, we can assume, of white men riding high on their horses to rule over those able (or authorized) to move only on foot. In the aftermath of several such protests, Roy Moore, the Republican Senate candidate from Alabama, rode his horse to the voting booth in a clear attempt to prove that the good old southern cowboy of yesteryear was alive and well. Moores Senate run was foiled not only because of his racism, but also because he sexually assaulted underage girls. Social media turned this into satire as Moores horse, Sassy, claimed #MeToo on her own Twitter feed.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

![De’Kari [De’Kari] - Voorheeze & Clarkola](/uploads/posts/book/140939/thumbs/de-kari-de-kari-voorheeze-clarkola.jpg)