To my sons, Sam and Michael, my stalwart companions during my travels throughout Oregon.

Acknowledgments

I offer my sincere thanks to my colleagues in the field of paranormal investigation, especially Jackie Ganiy, Loyd Auerbach, Nick Groff, Zak Bagans, and Jeff Bellanger, whose inspiration, support, and encouragement I highly value.

I am also grateful to Doug Carnahan, producer and host of the Haunted Truth radio show, who provided me forums to discuss my ideas and experiences with colleagues at Preston Castle and Virginia City; and to my friend Zak Bagans for opportunities to appear with him on the Travel Channel shows Ghost Adventures and Aftershocks.

Many thanks to my literary agent, Sue Clark, for the support and guidance that has proved to be invaluable on countless occasions and the staff of Pelican Publishing, who, for many years, have patiently guided me through the process of producing and marketing my books.

Introduction

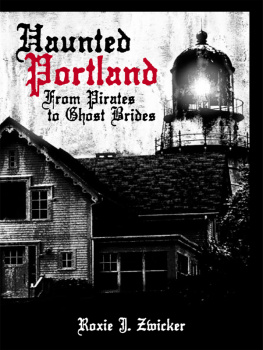

In 1843, Portland was nothing more than a canoe-landing site populated by fur traders who lived in log huts or tents. A drifter from Tennessee, William Overton, and lawyer Asa Lovejoy were among the muddy settlements residents. Both were anxious to get rich from the regions abundant natural resources, but neither owned land. Forming a partnership with 25 cents provided by Overton, the two men filed a claim on 640 acres and began clearing trees and building a road. Overton apparently grew tired of the work and moved on after selling his share of the claim to Francis Pettygrove. As a township took form, Pettygrove and Lovejoy realized the place needed a name. Each proposed to name the settlement after his hometown. Lovejoy suggested Boston while Pettygrove, who was from Maine, offered Portland. The toss of a penny settled the issue, with Pettygrove winning two of three flips of the coin.

Lovejoy and Pettygrove envisioned Portland as a great city built on the wealth of its natural resources. They also anticipated that quick prosperity would bring civilization to the Pacific Northwest. Instead, Portland went through a period of 30 years as a wild frontier town full of brothels, sailors boardinghouses, gambling dens, and saloons that were fronts for shanghaiing ship workers. It was not until the close of the 19th century that Portland was able to rid itself of detracting monikers such as the Forbidden City, the Unheavenly City, Mudville, and Log Town and become the Rose City.

The 20th century finally brought the civilization envisioned by Lovejoy and Pettygrove, as prosperity turned Portland into the jewel of the Pacific Northwest. Wealth generated by great lumber mills and the shipping industry built skyscrapers in downtown Portland and fine Victorian homes in several neighborhoods, which stand today as monuments to a vision that took several decades to fulfill. All too often, the history of those decades is composed of tragic stories arising from epidemics, great fires, floods, criminal activity, and shipwrecks. These tragedies are the basis of Portlands reputation as one of the most haunted cities in the Western U.S.

Epidemics of the mid-19th century and the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 brought tragedy to many Oregon families, ending lives at a young age and filling many pioneer cemeteries. The first recorded epidemic to hit the indigenous people of the region occurred in 1775. Fur trappers who arrived in ships brought smallpox, which decimated tribes along the Columbia River and north coast villages. Fur traders arriving in 1782 by overland routes brought a second wave of smallpox. This epidemic spread northward and was credited with wiping out half the Spokane Indian population. Smallpox struck again in 1801, leaving many Indians with pockmarked faces described by the explorers Lewis and Clark, when they arrived in 1805. Based on their report, historians believe that smallpox killed more than half of the 1800 Indian population of the western Columbia River region. Smallpox further decimated indigenous and immigrant populations in 1824 and 1853. The latter epidemic led to the opening of several pioneer cemeteries that exist today.

In 1830, malaria was imported into the Portland region. An epidemic of this disease started at Fort Vancouver and lasted four years. Accounts by officials at the fort suggest malaria nearly wiped out the entire Indian population along the lower Columbia River. The devastation caused by smallpox and malaria was so complete that after 1835, American and British immigrants to the area found few Indians. Consequently, place names that are in use today reflect the origins of the immigrantsPortland, Astoria, Salem, for examplenot traditional names used by indigenous peoples such as those found in Washington state that include Seattle, Yakima, and Tacoma.

The worldwide Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 caused more deaths in Portland than most other U.S. cities. Portland suffered 505 deaths per 100,000 population compared to Indianapolis, which had only 290 deaths per 100,000. Strict quarantine ordinances were enforced and public safety laws enacted, but thousands died, overloading funeral parlors and grave-digging crews at cemeteries. In many fascinating cemeteries, such as Brainard Cemetery, Gresham Pioneer Cemetery, and the old Jones Cemetery, victims are buried in clusters. Some markers indicate that entire families, comprised of young adults and infants, occupy a single grave. Their tragic demise seems to have created spirits who have yet to let go and move on.

As with many pioneer towns, catastrophic fires destroyed some coastal settlements and portions of Portland soon after the city was founded. Fast-moving blazes often destroyed crude wooden shacks and tents, catching many residents off guard and killing them. In 1860, most of Fort Vancouver was consumed in a blaze that started in a kitchen. On August 2, 1873, Portland volunteer firefighters responded to alarms that directed them to both wealthy and poor neighborhoods. Despite their efforts, more than 20 square blocks of the city were consumed, including Chinatown and riverfront warehouses. Historical accounts do not clearly state the death toll, but it is believed that it exceeded 100 persons. Fortunately, the elegant St. Charles Hotel, hailed by the Oregonian as the most magnificent structure on the northwest Pacific coast, was saved.

Large conflagrations are a thing of the past, but small fires occur often in and around Portland, creating fatalities that ultimately lead to paranormal activity. On December 9, 2010, a blaze swept through Lents Village, an apartment complex for senior citizens at 10325 SE Holgate Boulevard, Portland. Eighty residents were evacuated but one fatality occurred. On January 29, 2010, 26-year-old animal rights advocate Daniel Shaull staged a protest against Ungar Furs, a fur retailer, by dowsing himself with gasoline and igniting the vapor as he stood on the sidewalk at 1137 SW Yamhill Street. These tragedies have aroused the interest of ghost hunters, who have reported paranormal activity at the sites.