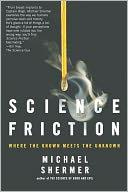

Praise for Science Friction

You may disagree with Michael Shermer, but youd better have a good reasonand youll have your work cut out finding it. He describes skepticism as a virtue, but I think that understates his own unique contribution to contemporary intellectual discourse. Worldly-wise sounds wearily cynical, so Id call Shermer universe-wise. Id call him shrewd, but it doesnt do justice to the breadth and depth of his inspired scientific vision. Id call him a spirited controversialist, but that doesnt do justice to his urbane good humor. Just read this book. Once you start, you wont stop.

Richard Dawkins, author of The Selfish Gene and A Devils Chaplain

It is both an art and a discipline to rise above our inevitable human biases and look in the eye truths about how the world works that conflict with the way we would like it to be. In Science Friction, Michael Shermer shines his beacon on a delicious range of subjects, often showing that the truth is more interesting and awe-inspiring than the common consensus. Bravo.

John McWhorter, author of The Power of Babel and Losing the Race

Michael Shermer challenges us all to candidly confront what we believe and why. In each of the varied essays in Science Friction, he warns how the fundamentally human pursuit of meaning can lead us astray into a fog of empty illusions and vacuous idols. He implores us to stare honestly at our beliefs and he shows how, through adherence to bare reason, the profound pursuit of meaning can instead lead us to truthand how, in turn, truth can lead us to meaning.

Janna Levin, author of How the Universe Got Its Spots

Whether the subject is ultra-marathon cycling or evolutionary science, Michael Shermerwho has excelled at the former and become one of our leading defenders of the latternever writes with anything less than full-throttled engagement. Incisive, penetrating, and mercifully witty, Shermer throws himself with brio into some of the most serious and disturbing topics of our times. Like the best passionate thinkers, Shermer has the power to enrage his opponents. But even those who dont agree with him will be sharpened by the encounter with this feisty book.

Margaret Wertheim, author of Pythagoras Trousers

Also by Michael Shermer

The Science of Good and Evil

In Darwins Shadow:

The Life and Science of Alfred Russel Wallace

The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience (general editor)

The Borderlands of Science

Denying History

How We Believe

Why People Believe Weird Things

Science Friction

SCIENCE FRICTION

Where the Known

Meets the Unknown

MICHAEL SHERMER

Owl Books

Henry Holt and Company, LLC

Publishers since 1866

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

www.henryholt.com

An Owl Book and  are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Copyright 2005 by Michael Shermer

All rights reserved.

Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd.

All artwork and illustrations, except as noted in the text, are by Pat Linse, are copyrighted by Pat Linse, and are reprinted with permission.

For further information on the Skeptics Society and Skeptic magazine, contact P.O. Box 338, Altadena, CA 91001, 626-794-3119; fax: 626-794-1301; e-mail:

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shermer, Michael.

Science friction: where the known meets the unknown/

Michael Shermer.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-7914-2

ISBN-10: 0-8050-7914-9

1. SciencePhilosophy. 2. ScienceMiscellanea. I. Title.

Q175.S53437 2005

501dc22

2004051708

Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets.

Originally published in hardcover in 2005 by Times Books

First Owl Books Edition 2006

Designed by Victoria Hartman

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

To Pat Linse

For her steadfast loyalty, penetrating intelligence, and illustrative originality

Contents

Introduction

Why Not Knowing

Science and the Search for Meaning

THAT OLD PERSIAN TENTMAKER (and occasional poet) Omar Khayym well captured the human dilemma of the search for meaning in an apparently meaningless cosmos:

Into this Universe, and Why not knowing,

Nor Whence, like Water willy-nilly flowing;

And out of it, as Wind along the Waste,

I know not Whither, willy-nilly blowing.

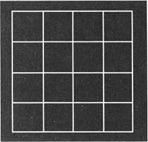

It is in the vacuum of such willy-nilly whencing and whithering that we humans are so prone to grasp for transcendent interconnectedness. As pattern-seeking primates we scan the random points of light in the night sky of our lives and connect the dots to form constellations of meaning. Sometimes the patterns are real, sometimes not. Who can tell? Take a look at . How many squares are there?

The answer most people give upon first glance is 16 (44) . Upon further reflection, most observers note that the entire figure is a square, upping the answer to 17. But wait! Theres more. Note the 22 squares.

Figure I.1

There are 9 of those, increasing our count total to 26. Look again. Do you see the 33 squares? There are 4 of those, producing a final total of 30. So the answer to a simple question for even such a mundane pattern as this ranged from 16 to 30. Compared to the complexities of the real world, this is about as straightforward as it gets, and still the correct answer is not immediately forthcoming.

Ever since the rise of modern science beginning in the sixteenth century, scientists and philosophers have been aware that the facts never speak for themselves. Objective data are filtered through subjective minds that distort the world in myriad ways. One of the founders of early modern science, the seventeenth-century English philosopher Sir Francis Bacon, sought to overthrow the traditions of his own profession by turning away from the scholastic tradition of logic and reason as the sole road to truth, as well as rejecting the Renaissance (literally rebirth) quest to restore the perfection of ancient Greek knowledge. In his great work entitled Novum Organum (new tool patterned after, yet intended to surpass, Aristotles Organon), Bacon portrayed science as humanitys savior that would inaugurate a Great Instauration, or a restoration of all natural knowledge through a proper blend of empiricism and reason, observation and logic, data and theory.

Bacon was no naive Utopian, however. He understood that there are significant psychological barriers that interfere with our understanding of the natural world, of which he identified four types, which he called idols: idols of the cave (peculiarities of thought unique to the individual that distort how facts are processed in a single mind), idols of the marketplace (the limits of language and how confusion arises when we talk to one another to express our thoughts about the facts of the world),

Next page

are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.